Tribal sovereignty, often viewed as a legal term, sits at the center of almost every issue affecting tribal nations existing within the United States’ geographical borders.

In its most basic sense, tribal sovereignty — the inherent authority of tribes to govern themselves — allows tribes to honor and preserve their cultures and traditional ways of life. Tribal sovereignty also is a political status recognized by the federal government, protected by the U.S. Constitution and treaties made generations ago, and upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Although the concept might seem relatively straightforward, there has been considerable disagreement between Indigenous groups and American government agencies over what tribal sovereignty actually entails, its implications and how tribes and states can or should work together to serve their constituents.

States and tribes continue to battle over land and jurisdiction in areas such as law enforcement. Government officials still are trying to understand all the ramifications of last summer’s U.S. Supreme Court decision in the landmark tribal sovereignty case McGirt v. Oklahoma.

Supreme Court justices affirmed that a giant swath of land in eastern Oklahoma the U.S. gave the Muscogee (Creek) Nation through treaties in the 1800s is, in fact, an “Indian reservation” and that the state of Oklahoma lacked jurisdiction to prosecute Jimcy McGirt, an enrolled member of the Seminole Nation, for serious crimes that occurred on Muscogee (Creek) Nation land.

Attorneys and policymakers across the country predict the ruling’s impact will extend well beyond Oklahoma and criminal prosecutorial matters.

Journalists planning to cover those impacts and tribal nations in general should have a basic understanding of tribal sovereignty and its significance to Indigenous people living in the U.S. Below, we provide important context.

We do not intend for this explainer to be exhaustive, but it is a starting point — and the first in a series of tip sheets, explainers and research roundups we’ll publish over the coming year to help journalists improve their coverage of Native Americans. In our next piece, we’ll take a much closer look at McGirt v. Oklahoma.

It’s worth noting that while federal government officials and documents often refer to Indigenous people in the U.S. as “Indians” or “American Indians,” the Native American Journalists Association has created a guide on Indigenous terminology.

Toward the bottom of this piece, we’ve gathered a variety of resources we think will help journalists, including links to academic papers on tribal sovereignty and a new website created by the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development and the Native Nations Center at the University of Oklahoma.

—–

Some key things journalists should know about tribal sovereignty:

- There are 574 federally-recognized American Indian and Alaska Native nations in the U.S., according to the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs. Each is a government entity with its own policies, processes and system of governance.

“Sovereignty for tribes includes the right to establish their own form of government, determine membership requirements, enact legislation and establish law enforcement and court systems,” according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

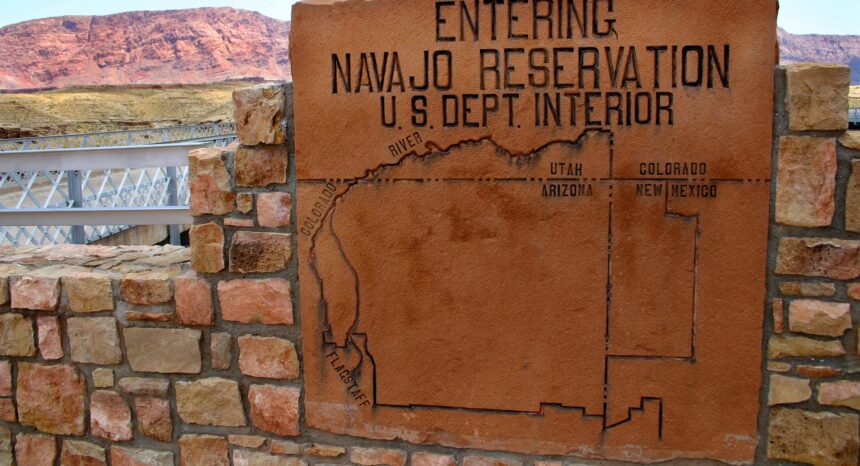

- Tribes vary in size. The largest in terms of both population and territory is the Navajo Nation, which stretches across 27,000-plus square miles in Utah, Arizona and New Mexico and, as Indian Country Today reports, had nearly 400,000 tribal members in May 2021. The Navajo Nation’s comprehensive budget for Fiscal Year 2021 is $1.25 billion.

The Augustine Band of Cahuilla Indians in California, on the other hand, had just 12 members in late 2019, the Palm Springs Desert Sun reports.

- Tribes set their own rules for who can join, so enrollment criteria vary from tribe to tribe. “Tribal enrollment criteria are set forth in tribal constitutions, articles of incorporation or ordinances,” according to the U.S. Department of the Interior.

Tribes often require evidence of tribal lineage. For example, a tribe might require documentation demonstrating that the person seeking to enroll is related to a tribal member who descended from someone named on the tribe’s base roll, or original list of members. Tribes may also require evidence of blood quantum. The federal Bureau of Indian Affairs issues what’s known as a Certificate Degree of Indian Blood, computed based on family lineage.

- Knowledge of treaties is important to tribal coverage. The U.S. Constitution calls treaties “the supreme Law of the Land.” Although they were negotiated generations ago — Congress stopped making treaties with tribes in the late 1800s — they remain relevant because they, among other things, outline the property rights and federal protections the U.S. agreed to give tribes in exchange for ceding millions of acres of their homeland.

The U.S. acquired much of its land through treaties, which “rest at the heart of both Native history and contemporary tribal life and identity,” Kevin Gover, director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, writes in 2014 in the museum magazine. “Approximately 368 treaties were negotiated and signed by U.S. commissioners and tribal leaders (and subsequently approved by the U.S. Senate) from 1777 to 1868. They enshrine promises our government made to Indian Nations.”

- The U.S. Constitution outlines the federal government’s relationship with tribes. “The Constitution gives authority in Indian affairs to the federal government, not to the state governments,” according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. “Just as the United States deals with states as governments, it also deals with Indian tribes as governments, not as special interest groups, individuals or some other type of non-governmental entity.”

- Attorneys commonly cite three historic court cases in legal challenges and legal analyses related to tribal sovereignty. In the 1832 case Worcester v. Georgia, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed that the Cherokee Nation was not subject to state regulation. Chief Justice John Marshall, writing for the court, explains that the Cherokee Nation “is a distinct community occupying its own territory … in which the laws of Georgia can have no force, and which the citizens of Georgia have no right to enter but with the assent of the Cherokees themselves …”

Today, states have no authority over tribes unless Congress gives it to them. In 1953, for example, Congress enacted Public Law 280, allowing six states — Alaska, California, Minnesota, Nebraska, Oregon and Wisconsin — to begin prosecuting most crimes occurring on tribal land. The federal law let other states decide whether they also wanted to make the change.

Additional resources

- McGirt and Rebuilding of Tribal Nations Toolbox: This website, created by the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development and University of Oklahoma Native Nations Center, provides a broad array of resources, including a series of briefing papers examining the ramifications of the McGirt decision in areas such as taxation, criminal justice and child welfare.

- Indigenous Data Sovereignty: This explainer, created by the Global Investigative Journalism Network and Native American Journalists Association, “explores what investigative opportunities exist for journalists regarding the bundle of issues known as ‘Indigenous data sovereignty.’”

- Shaawano Chad Uran, an enrolled member of the White Earth Nation and former professor of American Indian studies at the University of Washington, explains sovereignty and its importance in Indian Country Today, September 2018.

Law journal articles, academic papers worth reading

- Who Is an Indian Child? Institutional Context, Tribal Sovereignty, and Race-Making in Fragmented States

Hana E. Brown. American Sociological Review, August 2020. - Genetic Ancestry Testing with Tribes: Ethics, Identity & Health Implications

Nanibaa’ A. Garrison. Daedalus, March 2018. - Indian Education: Maintaining Tribal Sovereignty through Native American Culture and Language Preservation

Nizhone Meza. Brigham Young University Education and Law Journal, March 2015. - Myths and Realities of Tribal Sovereignty: The Law and Economics of Indian Self-Rule

Joseph P. Kalt and Joseph William Singer. Harvard University Faculty Research Working Paper Series, March 2004.

Expert Commentary