In the United States, important policy decisions are sometimes made through “direct democracy” rather than by elected representatives. Through ballot initiatives and statewide votes, citizens from Colorado to Massachusetts regularly decide on issues ranging from legalizing marijuana to regulating workers’ sick leave. Ballot measures have started to attract huge sums of money from interest groups as they seek to persuade voters to reject or approve ballot initiatives.

The influence of ballot initiatives, particularly when they relate to hot-button issues, on voter turnout and engagement has been widely explored in the academic literature. Perhaps the most famous recent case is the 2004 U.S. presidential election, where George W. Bush appeared to gain a decisive edge because 11 states had same-sex marriage initiatives on the ballot that year, helping to motivate socially conservative voters to turn out at the polls. But careful analysis reveals that the effect of such initiatives’ presence is not so clear cut — and may even be a myth. Some researchers have found that social-issue ballot measures may motivate turnout, while others are skeptical. A 2012 study in Political Research Quarterly by scholars at Stanford and U.C. San Diego analyzed data from 1870 to 2008 and concluded that, in general, “having direct democracy does not in and of itself lead to higher turnout.”

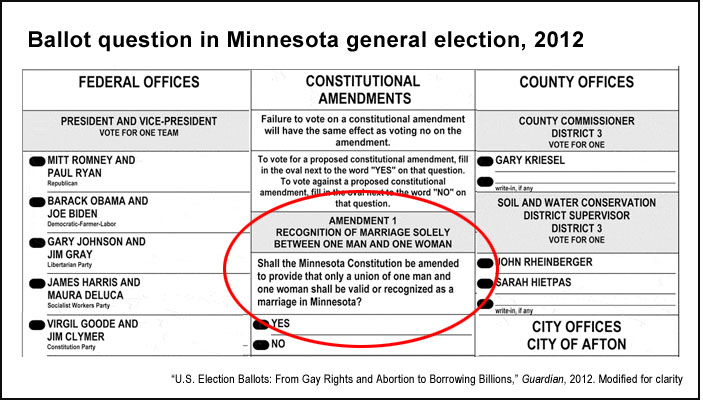

Campaigners have long seen ballot measure question “titles” (in effect, the headline above the ballot question) as an important tool to rally support, and numerous legal battles have been fought over how questions are worded. Below is an example of how these are often formatted, with an amendment or measure number, its title and the ballot question itself:

One reason for this is that it is generally believed that the wording of a ballot question can “frame” the way voters perceive an issue. The scholarly research on framing has a long history, with numerous studies showing how subtle shifts in language and associated imagery can influence decision-making, even where the underlying facts remain constant. From the foundational research work of Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky to newer communications work by the likes of James N. Druckman, social scientists have accumulated a large body of evidence that demonstrates how susceptible humans are to such cues.

In a 2014 study published in State and Local Government Review, “Ballot Titles and Voter Decision Making on Ballot Questions,” Jeff Hastings and Damon Cann of Utah State University try to empirically test how different ballot titles affect the decision of voters. The scholars describe framing as “the strategic selection of words [that] can bias the manner in which individuals cognitively process the information they receive.” The researchers presented 828 individuals with a same-sex marriage ballot question, headlined either “Eliminate the Right of Same-Sex Couples to Marry” or “Protect Marriage.” Those taking part could vote yes, no or abstain; the last option enabled the researchers to measure the potential effect of question titles on voter turnout.

Hastings and Cann acknowledge that “states often have laws prohibiting argumentative ballot titles and descriptions, but argumentativeness is undoubtedly in the eye of the beholder,” and thus it is essential to understand the power of framing effects in this context more precisely.

The key findings include:

- Approximately 39% of those presented with the “eliminate rights” title voted in favor, while the “protect marriage” frame led to slightly more than 50% doing so. The shift, about 12 percentage points, was solely attributable to the differences in the ballot title, and was sufficiently large that it would have changed the outcome of a vote.

- Titles appear to have the most influence over voters who are uncertain about the issue at hand. In particular, “the frames employed here seemed to affect whether individuals chose to vote at all on the ballot question or not.” This could mean that ballot titles and the framing of the issue could be crucial components in motivating citizens to get out the vote.

- The study finds evidence that these framing effects “are not spread generally across the population. Most specifically, individuals with a college education showed little or no susceptibility to the framing effects, while the effects were pronounced for individuals who had no college education.”

Hastings and Cann point out that “while the strong frames we used produced substantively meaningful shifts in outcomes, the shifts took place primarily by influencing whether individuals abstained rather than by leading an individual who previously supported same-sex marriage to oppose it (or vice versa.)” In the eyes of the authors, the results put emphasis on the danger which is posed by the potential abuse of power which lies in framing ballot titles and thus influencing outcomes. They acknowledge that it is impossible to present a “ballot title that truly has no frame. As long as a title must be given, it will have some frame; in the spirit of good governance, one may only hope that it is a [reasonable] frame with minimal effects on voters’ choices.”

Related research: A 2013 study in Perspectives on Politics, “‘Illegal,’ ‘Undocumented,’ ‘Unauthorized’: Equivalency Frames, Issue Frames and Public Opinion on Immigration,” explores the effect of word choice on people’s responses to survey questions. The researchers use the 2007 Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES) as a platform for research and systematically interchanged the words “illegal,” “undocumented,” “unauthorized” in questions on immigrant rights and asked respondents how they felt toward immigrants. Also of interest is a 2013 conversation with social scientist Dietram A. Scheufele on framing and political communication. The issues discussed include the effect of issue framing on the debate about global warming, online news comment threads and the U.S. government shutdown.

Keywords: voting, voter, democracy, voting booth, ballot, wedge issue, cognition

Expert Commentary