Elections in the U.S. are decentralized. Local jurisdictions or states, not the federal government, decide how to run them. There is no single voting method, and decisions on which voting method to use are often put to voters through ballot measures.

Plurality voting is one of the most common systems in the U.S. Most voters are likely familiar with it.

In a plurality system, the winning candidate needs to gain the most votes but does not need to break 50% of the vote total.

Another system, ranked choice voting, has become increasingly popular in the U.S., though it remains relatively uncommon.

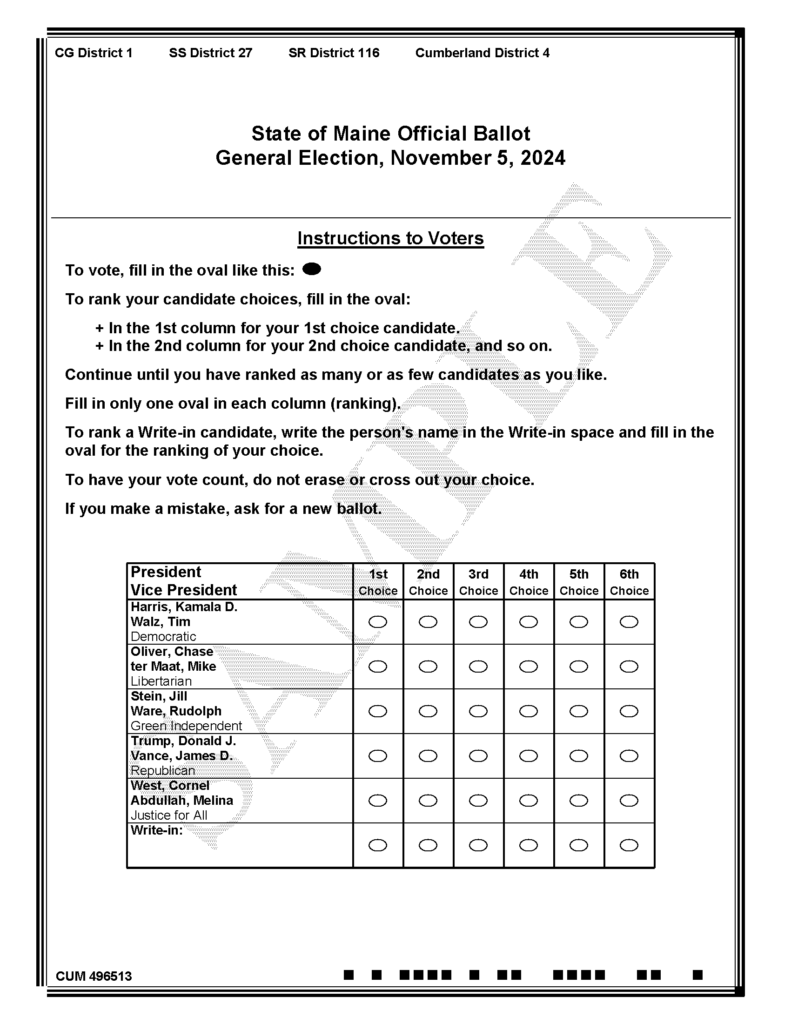

With ranked choice voting in elections with three or more candidates, voters rank their candidate choices from first to last. If there is no majority winner, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated.

Voters who ranked the eliminated candidate first then get their votes reallocated to their second choice. The counting continues until a candidate wins.

Today there are 45 cities, three counties and two states — Alaska and Maine — that use ranked choice voting in elections for some or all public offices, including at the federal level in the two states.

Most of the growth in jurisdictions adopting ranked choice voting has happened since 2018.

Before then, just 10 municipalities regularly used it, according to data from the nonprofit FairVote, which advocates for ranked choice voting.

Cambridge, Massachusetts, adopted ranked choice voting in 1941 and still uses the system. Ashtabula, Ohio, was the first municipality to adopt ranked choice voting, but voters repealed it in 1929.

Next week, voters in Colorado, Idaho, Nevada, Oregon and Washington, D.C. will decide on ballot measures that would have them join Alaska and Maine as ranked choice voting jurisdictions.

In October, the editorial board of The Washington Post endorsed those measures, writing that ranked choice voting “has myriad advantages” over the plurality system but that there is “no one trick to fix American democracy.”

Despite the increasing popularity of ranked choice voting, there has also been some backlash. Ten states have banned ranked choice voting, all through legislation, since 2020. The ballot measure in Idaho, if approved, would overturn a 2023 law banning ranked choice voting there.

But in Alaska, ranked choice voting is up for repeal by ballot measure this November, just four years after voters approved the system. A ballot measure in Missouri, if successful, would add that state to the list of those banning ranked choice voting.

Arguments for and against ranked choice voting

Journalists often turn to organizations that favor ranked choice voting, such as FairVote, for help explaining to audiences the arguments advocates make.

One argument is that ranked choice voting saves money. There’s no need to hold a runoff election if no candidate achieves a majority — the votes are simply reallocated to the second and third choices and so on. But only Georgia, Mississippi and Louisiana require runoffs if there’s no majority candidate, according to Ballotpedia.

Every change in a voting system comes with upfront costs, according to a 2022 report from the National Conference on State Legislatures. The average cost for a local election jurisdiction to switch from a plurality to a ranked choice system is about $40,000, according to the NCSL, though costs vary depending on the size of the jurisdiction, local labor costs and fees for lawyers or other consultants.

“Costs can be offset by savings depending on circumstances,” according to the report. “In fact, switching to [ranked choice voting] can be a net money saver if, by using RCV, an election and a runoff election can be combined into a single election, or a primary election can be consolidating with a general election. Total savings can be significant.”

Advocates also argue that ranked choice voting encourages diverse viewpoints in political campaigns.

“More than one-third of voters are Independents, yet they have little influence in government because it is difficult for Independent candidates to get elected under plurality voting rules,” according to FairVote. “[Ranked choice voting] can improve their representation at the state and federal levels of government, allowing supporters of Independent and third-party candidates to rank their preferred candidate first without ‘wasting’ their votes or ‘spoiling’ the election outcome.”

There are also think tanks and nonprofits against ranked choice voting.

Those detractors often counter that ranked choice systems are confusing for voters and that voters’ ballots can be voided if they’re not filled out correctly.

“[R]anked-choice voting results in votes being tossed out, introduces confusion and uncertainty to voting, and results in diminished voter confidence in our elections,” writes Andrew Welhouse, a senior writer with the Foundation for Government Accountability, a think tank based in Naples, Florida. In 2022, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed a bill banning jurisdictions in the state from using ranked choice voting.

Political scientists, whose academic publications are subject to peer review, have in recent years examined claims for and against ranked choice voting. Those researchers can often offer reporters nonpartisan perspectives backed by scientific rigor.

One big thing researchers emphasize is that there is no perfect voting system. Plurality elections, for example, can send candidates to office who fail to achieve majority support, and there are voided ballots in plurality systems.

Here, we cover what two recent papers say about how ranked choice voting has worked in practice, as well as findings from past research for further context.

Electoral failures

Journalists digging into the research on voting systems might see the phrase “failure” or that a voting system “failed.” For political scientists and other researchers studying voting systems, a failure doesn’t mean a system didn’t work as intended — it doesn’t necessarily mean there was fraud, corruption or some other malfeasance. It means the system failed to live up to the expected outcomes of another system.

For example, a majoritarian failure happens when ballots were cast and counted and someone was duly and fairly elected to office, just not with a majority vote. Majoritarian failures happen in both plurality and ranked choice systems, researchers have found.

Another type of failure is a Condorcet failure, named for 18th century French mathematician and philosopher Marie-Jean-Antoine-Nicolas de Caritat, Marquis de Condorcet, pronounced “condor-say.” A Condorcet failure happens when the ranked choice winner would not have won head-to-head matchups with at least two other candidates.

This happened in Alaska in 2022 following a special election for the state’s at-large congressional seat, with Mary Peltola, Sarah Palin and Nick Begich III running. It was the first statewide election in Alaska to use ranked choice voting.

Begich would have won head-to-head general election matchups against Peltola and Palin, according to a June 2023 paper in the Journal of Representative Democracy. For election researchers, the Condorcet winner is typically a strong candidate who should win any type of election. But Begich didn’t make it to the final round of counting.

“There are voting theorists who would look at that Alaska data and say, ‘the instant runoff method chose the wrong person — it should have been Nick Begich,’” explains Adam Graham-Squire, an associate professor of mathematics at High Point University and one of the paper’s authors.

Begich was eliminated after the first round, gaining fewer votes than Palin, who was the Republican Party nominee for vice president in 2008. Palin got 31% of the first-round vote, while Peltola, a Democrat, got 40%. After Begich voters’ second choices were reallocated, Peltola won with 51% of the vote to Palin’s 49%.

In November 2022, Alaskans voted again in the regular election for the seat, with the same three candidates running. Peltola won with 55% of the vote after three rounds of counting. This suggests Condorcet failures may not matter much to voters, Graham-Squire says.

“They had a repeat of that election three months later, and Mary Peltola won again, and won even more strongly,” Graham-Squire says. “Even though the knowledge was out there that there was a Condorcet winner who lost the election — and maybe that didn’t filter out to Alaskans, but I think even if it did, they probably wouldn’t care — and that didn’t seem to matter to the average voter.”

And it’s rare for the Condorcet winner to lose a ranked choice vote.

The authors of an October 2022 paper in the Journal of Representative Democracy collected data on ranked choice elections in Maine, 18 municipalities across the country and ranked choice elections for president of the American Psychological Association, spanning a total of 271 elections from 1998 to 2021.

Most elections in the database were held in Alameda County, California; Cambridge, Massachusetts; Minneapolis, New York City and San Francisco; and among APA members.

The authors found one ranked choice election, the 2009 mayoral vote in Burlington, Vermont, that did not produce the Condorcet winner.

“In practice there simply aren’t as many ‘close’ elections as what might be predicted by the theoretical literature, but such elections will sometimes occur and therefore the historical and ongoing debate about the ‘best’ voting method is not purely an academic exercise,” conclude the authors, David McCune, a professor of mathematics at William Jewel College, and Lori McCune, a professor of mathematics at Missouri Western State University.

Graham-Squire notes that one of the surprising takeaways from his paper, written with David McCune, was the proportion of majoritarian failures in ranked choice elections. Ranked choice voting advocates may argue that the system elects majority candidates, but journalists should ask how advocates define a majority.

The answer may not be so simple.

This is because some ballots are likely to be eliminated each counting round. Ballots may be eliminated because the voter did not fill them out correctly, or because of something called truncation. A truncated ballot is “exhausted” and eliminated when there are no more candidates on it left to count, since voters do not have to rank every candidate.

Imagine an election with four candidates. A voter ranks two of them. In the first round of counting, their top-choice candidate is eliminated. In the second round, their second-best choice is eliminated. The counting is down to the final two candidates. But this voter’s ballot is truncated because the voter didn’t rank the final two candidates — there’s no way for election officials to tally their selection in final round. For that race, the ballot is exhausted.

Truncation can also happen by statute, as some ranked choice jurisdictions only allow voters to rank a certain number of candidates. Voters in New York City, where there is often a crowded Democratic primary field for mayor, can rank up to five candidates. In Minneapolis, voters can rank up to three candidates. When there are more candidates than ranks, the odds of a ballot being exhausted increases with each counting round.

In a ranked choice election, the winning candidate has to achieve a majority of the votes available in the final round of counting, but this may not represent a majority of the original votes cast, Graham-Squire explains. This is what he and McCune found happened surprisingly often in the ranked choice elections they analyzed — there was a majoritarian failure in 52.4% of those elections, when accounting for the original number of votes cast, not just those that counted in the final round.

It’s important that journalists remind audiences that neither plurality system nor ranked choice systems are perfect. Plurality systems also experience majoritarian failures, as Graham-Squire and McCune note in their paper. And for as much as “majority rule” is a staple of American political discourse, voters may not, in fact, be overly concerned with majoritarian failures, they write.

“For example, if enough voters care only about one or two candidates and are indifferent among the rest, then no voting method will be able to find a ‘majority winner,’ and it is not the fault of [ranked choice voting] that the election produces a majoritarian failure,” write Graham-Squire and McCune.

Is ranked choice voting too complicated?

By nature, ranked choice voting is more complicated than choosing one candidate. A common argument from ranked choice detractors is that it is not just more complicated, it is too complicated for voters and leads to spoiled ballots.

A vote is spoiled when it cannot be counted, usually because the voter did not mark their ballot correctly for a race or ballot measure, either unintentionally or deliberately. Spoiled votes happen in any system, and often they often happen when a voter’s intentions are unclear, such as from undervoting or overvoting.

Undervoting is when a voter does not choose any candidate for an office. This is not necessarily because the voter didn’t understand how to mark their ballot. It could be the voter chose not to vote in that race.

Overvoting is when a voter chooses too many candidates — for example, marking multiple candidates for first place, or marking both candidates in a two-candidate race.

Research suggests that ballot errors happen at similar rates across voting systems, but there may be differences in errors among demographic groups.

In a December 2023 paper in American Politics Research, Lindsey Cormack, an associate professor of political science at Stevens Institute of Technology, examines disqualified ballots during New York City’s first election with ranked choice voting, the 2021 mayoral primary. Cormack finds fewer ballots voided, on average, per state assembly district than in previous plurality primaries in 2017 and 2013.

In breaking down the data for 2021 by race, education and income, Cormack finds the most consistent relationships, within assembly districts, between higher rates of ballot spoiling and lower levels of education, and ballot spoiling and lower median annual income.

Mail-in ballots were also more likely than in-person votes to be spoiled because there is no quick way to fix them, Cormack explains. New York City uses paper ballots, and when voters cast their ballots in person they feed them into a digital scanner that alerts them if there is a problem with how they filled it out, giving them the chance to fix, or “cure” their ballot on the spot.

“The thing that’s concerning to me is — we do throw out ballots every year, there are errors, there is mismarked stuff — but I don’t think it’s normatively good to have that be correlated with things like levels of education or levels of income,” Cormack says. “You want it to be kind of idiosyncratic.”

It’s important to note that the 2021 mayoral primary was New York City voters’ first experience with ranked choice voting, and it is not necessarily safe to assume that occurrences in one election will happen again. But there is past research analyzing multiple ranked choice elections over a period of years.

The authors of a 2008 paper in American Politics Research looked at overvotes and undervotes across three ranked choice election years in San Francisco, which implemented the system in 2004. The results were somewhat mixed, suggesting that overvote errors persisted across the elections, particularly in areas with higher shares of Black residents. However, undervote rates were lower overall, compared with past plurality elections.

Co-author Francis Neely, now a professor emeritus of political science at San Francisco State University, returned to this question with more data in a 2015 paper published in the California Journal of Politics and Policy.

Neely and Jason McDaniel, an associate professor of political science at SFSU, caution that their research is limited to one jurisdiction, writing that “voters’ experiences elsewhere will differ.” In the 2015 paper they find similar overvoting trends in races with multiple candidate choices, no matter whether those races use ranked choice or another system.

“[C]onsistently, precincts where more African-Americans reside are more likely to collect overvoted, voided ballots,” write Neely and McDaniel. “And this often occurs where more Latino, elderly, foreign-born, and less wealthy folks live.”

Cormack notes that when municipalities use ranked choice voting for some but not all elections, it may take longer for some voters to learn the system.

“We don’t use it in every election in New York City,” Cormack says. “We only do it in municipal primaries, so it’s something where you have these waves of standard elections and then you whiplash back into this for one municipal primary. I’m not sure that we’re going to see a lot of learning next time around — we’ll find out.”

3 things journalists covering ranked choice voting should know

Journalists should contact local academics who have studied ranked choice voting for help understanding the benefits and drawbacks of using the system in the communities they cover.

Or, if there is scant research in your area, consider partnering with local political scientists to conduct research that can inform your reporting.

READ: 9 TIPS FOR EFFECTIVE COLLABORATIONS BETWEEN JOURNALISTS AND ACADEMIC RESEARCHERS

Here are three more things journalists covering ranked choice voting should consider.

1. Find stories about public outreach efforts.

What sort of outreach are elected leaders and other organizations doing to ensure people understand ranked choice voting? Are they holding in-person events in communities that may need additional help understanding ranked choice voting? Or, maybe they’re getting creative — that would be a story worth covering. In Anchorage, Alaska, a drag show at a café allowed people to try out ranked choice voting by selecting their favorite performers.

In multilingual areas, find out how information is translated into languages other than English. In New York City, Cormack says she served as an election worker in 2021 and recalls interpreters being frustrated by a lack of an agreed upon phrase in Spanish for ranked choice voting. She wonders whether using other phrases, such as “you’re going to pick sequentially,” or “you’re going to pick your top five,” could have affected how voters whose primary language isn’t English understood how to fill out their ranked choice ballots.

2. Don’t over-rely on advocacy groups.

Ranked choice voting may or may not be a better choice than plurality voting in some municipalities or states for a variety of reasons. As with any issue, seek sources — such as academic researchers — who can provide independent perspectives on advocacy group claims.

“There’s this level of scrutiny that isn’t happening because there’s not a lot of great research out there, so it’s not really journalists’ fault that they’re falling back on the policy entrepreneurs’ lines on it,” Cormack says. “But it’s something where I know people within academia are sort of rattling around like ‘Oh God, how do you get out ahead of this?’”

Put another way, it’s a good bet that academics studying voting systems will be happy to take calls from reporters.

3. Ranked choice systems produce more data than plurality systems.

Ranked choice voting gives a clearer sense of voter preferences than plurality voting — it offers shades of gray, rather than black and white. Graham-Squire points to the 2022 special election in Alaska to illustrate this point.

In a regular, plurality Republican primary, data indicates that Palin would have beaten Begich, Graham-Squire says. Palin would have then faced Peltola in the general election, where the data indicates she would have lost. In this alternate universe, Republicans may have bemoaned having picked the more politically extreme Palin over the more centrist Begich in the primary.

But the outcome would have been the same as what happened in the ranked choice vote, with Peltola winning. Point is, Condorcet and other types of electoral failures happen in plurality systems. There’s just not enough data to identify those failures compared with a system that allows a rank of preferences, Graham-Squire explains.

“In the situations I’ve seen where they’ve repealed instant runoff, it didn’t actually fix the issue they were concerned about,” Graham-Squire says.

Further reading

Come-From-Behind Victories Under Ranked Choice Voting and Runoff: The Impact on Voter Satisfaction

Joseph Cerrone and Cynthia McClintock. Politics and Policy, June 2023.

The Curious Case of the 2021 Minneapolis Ward 2 City Council Election

David McCune and Lori McCune. The College Mathematics Journal, May 2023.

Ranked Choice Voting and the Spoiler Effect

David McCune and Jennifer Wilson. Public Choice, April 2023.

Demographic Differences in Understanding and Utilization of Ranked Choice Voting

Todd Donovan, Caroline Tolbert and Samuel Harper. Social Science Quarterly, 2022.

The Prevalence and Consequences of Ballot Truncation in Ranked Choice Elections

D. Marc Kilgour, Jean-Charles Grégoire and Angèle M. Foley. Public Choice, October 2019.

Ballot (And Voter) “Exhaustion” Under Instant Runoff Voting: An Examination of Four Ranked Choice Elections

Craig M. Burnett and Vladimir Kogan. Electoral Studies, March 2015.

Overvoting and the Equality of Voice Under Instant-Runoff Voting in San Francisco

Francis Neely and Jason McDaniel. California Journal of Politics and Policy, 2015.

Expert Commentary