It hardly bears rehashing that Democrats and Republicans view the 2020 general election in moralistic, good-versus-evil terms. Case in point: An Oct. 19 survey from the nonprofit, nonpartisan Public Religion Research Institute finds 78% of Democratic respondents think the Republican Party has been overtaken by racists while 81% of Republicans think the Democratic Party has been overtaken by socialists. The survey interviewed about 2,500 randomly selected adults across all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

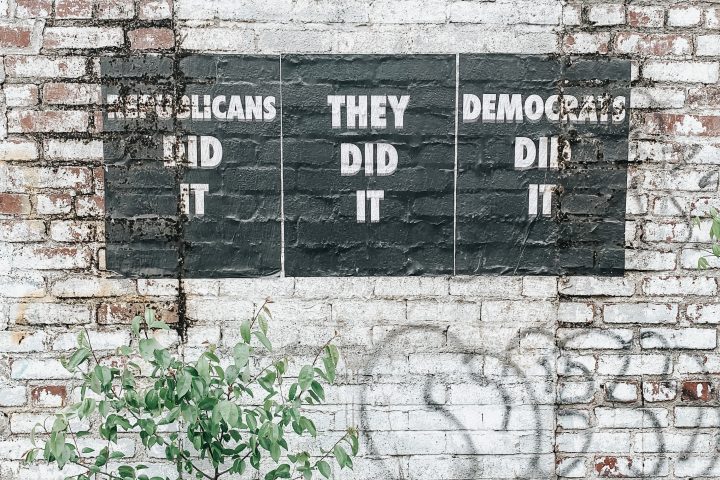

Political scientists in recent years have used various terms to describe America’s deep political divide, including “affective polarization,” “social polarization” and “tribalism.” The authors of a new paper in Science settle on “sectarianism” as most reflective of the current political state, in which Democrats and Republicans dislike members of the other party more than they like members of their own.

“The existing words don’t incorporate the moral component,” says Northwestern University social psychology professor Eli Finkel, one of the paper’s 15 authors. “They don’t fully capture this idea that our views are morally right in this absolute sense.”

The core of tribalism, for example, is kinship — members of a tribalistic group feel a familial bond with one another. The core of sectarianism, by contrast, is religion, faith and “moral correctness and superiority of one’s sect,” the authors explain.

In other words, a political sect isn’t bonded in the way that a family is — a brother and sister might drive each other crazy but still innately love each other and remain bonded by blood. The authors argue that American political sects are bonded by faith that their side is morally superior to the other — echoing the ties that sometimes bind the religiously faithful. The effect is that politicians have little incentive to represent all their constituents in policy and lawmaking, since political sectarians rarely cross the aisle to vote for candidates outside their party.

There might be some logic to sectarianism if Democrats and Republicans disagreed not solely based on their party identification but on the underlying ideas their parties push. That’s not the case, according to the authors, citing the 2015 paper, “Red and Blue States of Mind: Partisan Hostility and Voting in the United States” in Political Research Quarterly.

The authors of the new paper, “Political sectarianism in America,” explain that “the causal connection between policy preferences and party loyalty has become warped, with partisans adjusting their policy preferences to align with their party identity.”

It is not a purely academic exercise to develop accurate language to describe America’s fractured politics. Rhetorical precision can help people understand real-life consequences, like the potential for violence on and after Election Day.

“The issue is when things get sectarianized, when the other side is so iniquitous — ‘those people are just so awful’ — then the stakes seem high enough that violence in pursuit of your political aims becomes less unacceptable, that the violation of democratic principles becomes less unacceptable,” Finkel says. “That makes sense because these are moral tradeoffs: ‘I could compromise a little bit of democracy if it will increase the likelihood that the other side stays out of office.’”

It’s getting cold in here

Researchers at American National Election Studies, a collaboration between Stanford University and the University of Michigan, have for decades produced surveys during national election years that ask participants how “hot” or “cold” they feel about opposing parties. Researchers specifically ask about “feelings toward some of our political leaders and other people who are in the news these days.”

Participants then rate their feelings toward politicians on a temperature-like scale, with 100 degrees being “very warm or favorable,” 50 degrees indicating no feeling and 0 degrees being “very cold or unfavorable.” The final result is what ANES calls “feeling thermometers.” Political scientists commonly use ANES feeling thermometers in research on polarization.

Dubbing it the “ascendance of political hatred,” the authors of the current paper use results from the past 40 years of ANES feeling thermometers to show that Democrats and Republicans “have grown more contemptuous of opposing partisans for decades, and at similar rates.” Since 2012, “this aversion [has] exceeded their affection for copartisans.”

Put another way, sectarian political divisions have become so entrenched over the past decade that Democrats and Republicans dislike members of the other party more than they like members of their own party. And yet “political sectarianism is neither inevitable nor irreversible,” according to the authors.

Three reasons — three solutions

The authors, an interdisciplinary group of political scientists, psychologists and sociologists, offer three reasons for the rise of American political sectarianism.

The first has to do with demographic sorting between the Democratic and Republican parties. The parties tend to cleanly sort between liberals and conservatives, as well as by educational, racial, religious and geographic categories. These “mega-identities,” as the authors put it, can “change other identities, as when partisans alter their self-identified religion, class or sexual orientation to align with their political identity.”

The authors note that this sorting by ideology and demographics has happened concurrent with Republicans and Democrats overestimating their aggregate differences.

“For example,” they write, “Republicans estimate that 32% of Democrats are LGBT when in reality it is 6%; Democrats estimate that 38% of Republicans earn over $250,000 per year when in reality it is 2%,” citing the 2018 paper, “The Parties in Our Heads: Misperceptions About Party Composition and Their Consequences” in The Journal of Politics.

The second reason that the authors point to is partisanship in broadcast news media, particularly since Ronald Reagan’s presidential administration ended the Federal Communications Commission’s fairness doctrine in 1987.

Under the fairness doctrine, if radio and television broadcasters wanted to keep their FCC licenses, they had to offer a fair opportunity for contrasting viewpoints to be heard on issues of national importance, such as presidential campaigns. The doctrine wasn’t without critics, but its termination presaged the rise of conservative pundits and news networks, like Rush Limbaugh and Fox News, and the leftward turn of networks like CNN and MSNBC. Today, social media echo chambers play an outsize role in perpetuating political sectarianism, according to the authors.

The final reason the authors offer for American sectarianism is that politicians and political elites themselves are more likely today to push ideologically extreme ideas and language, “with Republican politicians moving further to the right than Democratic politicians have moved to the left.” Politicians in the major political parties have also become more financially reliant on donors who hold extreme ideas, the authors explain.

Yet there are pathways, both in terms of policy and personal accountability, to reduce political sectarianism, according to the authors.

The first pathway: Individuals who take it upon themselves to understand and correct misconceptions about members of the other party and to communicate directly with them. Such efforts may also include civil, religious and media leaders who are committed to “bridging divides,” the authors write.

Social media interventions are another way to reduce sectarianism. Interventions might include crowdsourced judgments of news source quality being baked into algorithms so that hyper-partisan or false content doesn’t often show up in users’ news feeds.

The final pathway toward reduced sectarianism in America involves incentives for politicians to avoid polarizing language and policies. The authors suggest these incentives might include campaign finance reform and minimizing partisan gerrymandering to “generate more robust competition in the marketplace of political ideas” and elect fewer extremists to the federal government.

“In a very real sense, the government kind of does start with us,” Finkel says. “If we have the inclination, we as in the general populace, to say, ‘I am going to try to resist the most polarizing elements on my side or the other side and not retweet the most outraged people but rather the people trying to listen,’ if we get a groundswell of that, I think there’s a chance we could start to make a real dent in these problems.”

For more JR coverage of the 2020 general election, check out how news outlets project presidential winners, research on the risks of voting by mail or in person and how the electoral college works.

Expert Commentary