After the most recent government shutdown, from October 1 to 16, 2013, American politics seem more polarized than ever. While the United States suffered through a shutdown 17 years ago, this time the economy was still recovering from the Great Recession, and the consequences were that much more painful: According to the rating agency Standard & Poor’s, the shutdown cost $24 billion and cut the growth rate by 0.6%.

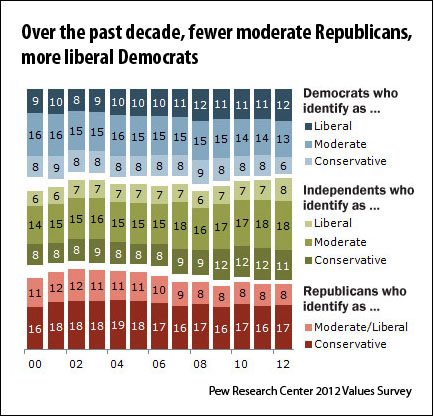

Results from recent Pew Research Center surveys indicate that Democrats and Republicans continue to move away from each other on the ideological spectrum: “Across 48 different questions covering values about government, foreign policy, social and economic issues and other realms, the average difference between the opinions of Republicans and Democrats now stands at 18 percentage points … nearly twice the size of the gap in surveys conducted from 1987-2002.” At the anecdotal level, polarization just seems to be “in the air” — from the television airwaves to the blur of social media streams. Indeed, other recent studies on polarization note that political discourse on social media is increasingly fractured, with a high percentage of Twitter users, for example, providing links primarily to websites with similar ideological content.

Although the latest data from the American National Election Study suggests that Americans are indeed moving further apart, Princeton political scientists Lori Bougher and Markus Prior call into question some of the survey data and methods. Such claims and counter-claims are part of a long-running research debate, going back more than a decade now, about the true nature of polarization in America. While many agree that polarization has grown more acute at the “elite” level (Congress and party leaders), some say that the pattern is less pronounced at the mass level.

Morris Fiorina, a professor and senior fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, has been one of the strongest voices in opposition to the claim. He co-authored Culture War? The Myth of a Polarized America, first published in 2004. In 2005, Alan Abromowitz of Emory University and Kyle L. Saunders of Colorado State University responded in their paper, “Why Can’t We All Just Get Along? The Reality of a Polarized America.” They assert that these divisions “reflect fundamental changes in American society and politics that have been developing for decades and are likely to continue for the foreseeable future.”

Journalist Bill Bishop’s 2009 book The Big Sort: Why the Clustering of Like-Minded America Is Tearing Us Apart added further fuel to the debate: It asserted that we are witnessing a geographic political polarization because Americans are increasingly choosing to live in neighborhoods filled with like-minded people. In 2012, Fiorina and Samuel J. Abrams (a frequent co-author, from Sarah Lawrence College) responded in an article for PS: Political Science and Politics, “‘The Big Sort’ That Wasn’t: A Skeptical Reexamination,” which rejected Bishop’s claim. They assert that “there is no evidence that a geographic partisan ‘big sort’ like that described by Bishop is ongoing, and even if it were, its effects would be far less important than Bishop and those who support his thesis fear.”

The research on this topic gets even more nuanced when other areas of life are considered — and when the topic gets more personal. Casey A. Klofstad of the University of Miami, Rose McDermott of Brown University and P.K. Hatemi of Pennsylvania State University explore a different possible reason for the increased political polarization: dating. In a 2013 study published in Political Behavior, “The Dating Preferences of Liberals and Conservatives” (open version here), the authors use a random sample of about 3,000 online dating profiles to determine whether “positive mate assortation — like seeks like — on nonpolitical factors such as lifestyle and demographics could lead to inadvertent assortation on political preferences.”

Building on prior scholarship that demonstrates a link between the political preferences of parents and their children, the researchers test the hypothesis that “spousal concordance on political preferences could be due to mates seeking others who are similar to themselves on traits related to ideology.”

Study findings include:

- Although the profiles do not place heavy emphasis on politics, “daters appear to sort on other traits, which correlate with ideology. As such, individuals may find their ideological matches by assorting on characteristics informed by the social environments where individuals reside, and these traits are related to political preferences in undefined yet systematic ways.”

- With a few exceptions, both liberals and conservatives in the sample generally preferred to date people like themselves: “Positive assortion behavior is pervasive.”

- Some cases were found in which liberals and conservatives take different dating approaches. For example, conservatives are more likely than liberals to want to date someone who shares their relationship status and views on tobacco usage, while more progressively minded daters are more willing to date someone with a different body type than their own.

- “If all things remain constant, the number of individuals in [the] extreme left and right ideological tails will be almost 2 times greater in 5 generations and 2.5 times greater in 25 generations merely as a result of assortive mating.”

The authors conclude that the “increasing prevalence of Internet dating may hasten the process of assortation, and potentially political polarization as well, as individuals can easily select potential mates that are similar to themselves by searching through detailed profiles before investing the time and energy involved with courtship…. This possibility raises a larger issue: people may select partners over the Internet along different dimensions, or in different ways, than they would in ‘real life.’”

Related research: Some earlier studies have suggested that people tend to avoid politics more in the initial stages of finding a mate. Other work has found that politics play a significant role as social relationships more broadly are created.

Keywords: polarization, political extremism, mate selection, dating

Expert Commentary