Small-town commercial districts are potential job creators for thousands of rural communities in the U.S.

New research in Economic Development Quarterly reveals how the nation’s most widely known downtown redevelopment effort, the nonprofit Main Street Program, affects economic outcomes.

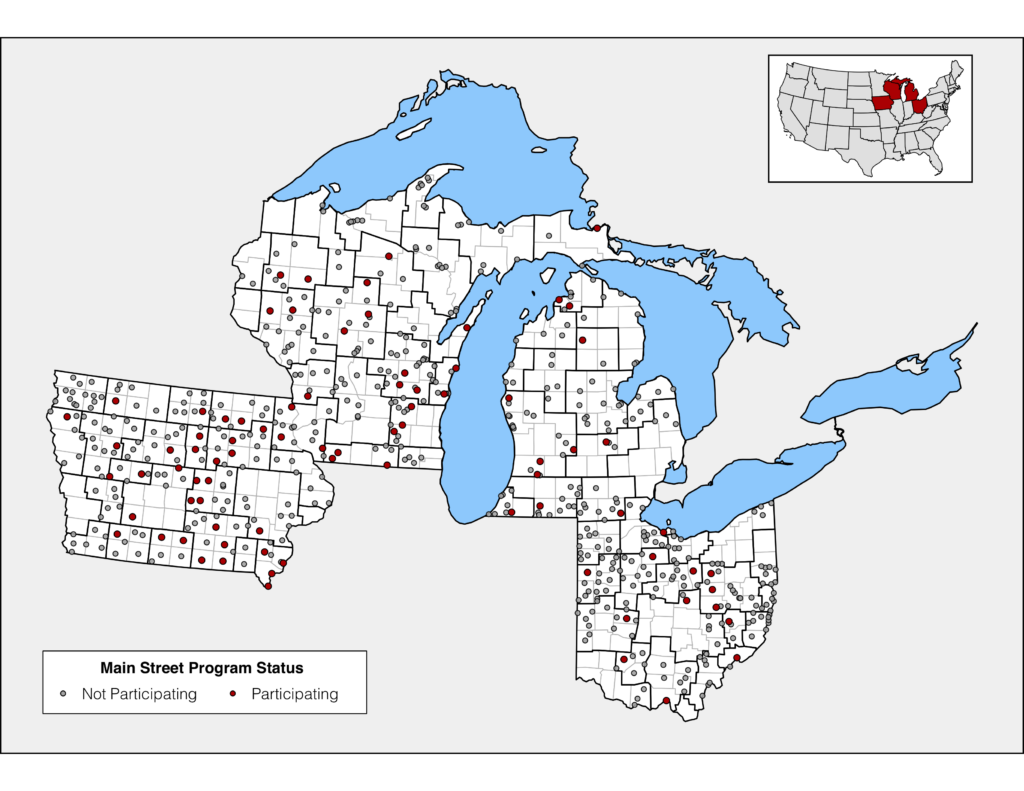

The paper looks at two measures of economic vitality — job creation and new business formation — linked to 494 small-town Main Street programs introduced in Iowa, Michigan, Ohio and Wisconsin from 1997 to 2019. It finds no evidence the programs substantially affected those measures of economic success in communities in three of the states.

But in Iowa, the results were different. Participation led to 20 new downtown retail jobs per 1,000 residents, two new downtown businesses per 1,000 residents, and $650 more in taxable retail sales per resident on average for the five years after a Main Street program launched.

“These findings suggest that Main Street Program participation effects are not generalizable across states and that implementation and local context matter,” writes study author Andrew Van Leuven, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Missouri. He points out that community goals vary and economic success can be defined in other ways — for example, by how a Main Street revitalization program affects home prices.

“The concept of economic vitality is ambiguous,” he says.

Van Leuven focused on Iowa, Michigan, Ohio and Wisconsin for the period studied because of data availability and because those states had consistent, statewide Main Street programs over those decades.

The communities studied had an average population of 6,325, with a low of 776 and a high of 36,837. For some towns, success might not be measured in jobs created or new businesses. A town might measure success by the number of historic buildings preserved, or whether the program leads to a safe, central space for community members to gather.

In related research under review at a separate academic journal, Van Leuven finds that in Ohio sale prices tend to be higher for houses farther from downtowns — except in towns that participate in the Main Street Program, where the relationship flips.

“In those towns, in the years after the program gets adopted, the houses closer to downtown increase in value,” Van Leuven says. “Again, that’s just another way to evaluate economic vitality.”

Iowa’s success story

The nonprofit National Trust for Historic Preservation launched the Main Street Program in 1977 as a pilot in Galesburg, Illinois; Madison, Indiana and Hot Springs, South Dakota. The program went national three years later. As Van Leuven writes, the program began as a response to widespread car ownership pushing commercial districts into low-density areas outside of towns and close to major roadways.

Towns that adopt the program make a long-term commitment to pursue strategies that enhance the economic vitality, design, promotion and organization of their pedestrian-friendly downtowns. The town’s first step is to hire a full-time director to manage its program, but community members also volunteer significant time and energy over the years, Van Leuven explains. State coordinators and the national program provide informational resources and technical expertise.

While most Main Street communities are small towns like Mount Vernon, Iowa and Millersburg, Ohio, big cities like Boston, Orlando, and Washington, D.C. also participate. There are roughly four dozen Main Street coordinating programs nationwide. Some coordinating programs operate as nonprofits while others are state funded. Some states, like Iowa, have highly engaged statewide coordination for their local Main Street efforts. Dubuque, Keokuk and several other communities there have participated since the early- and mid-1980s.

Longstanding institutional knowledge, plus a strong small-town culture, are two reasons the program has yielded new jobs and businesses, says Main Street Iowa state coordinator Michael Wagler.

“We have approximately 940 towns and three-quarters of those are under 5,000 in population,” Wagler says. “So we have a lot of communities that have a sense of self-sustainability. That really drives some of the local entrepreneurialism.”

Iowa has 55 active Main Street programs across the state, Wagler says. COVID-19, which in March 2020 shuttered retail shops, restaurants and other businesses that rely on personal transactions, also brought new challenges for Main Street programs. Wagler’s team held multiple monthly video calls with Iowa Main Street directors to discuss disbursing federal aid funds, how to interpret federal and state health guidance, and to act as a sounding board for the economic and emotional toll of the pandemic.

“We did a lot of listening,” he says. “I found out personally and professionally that just listening sometimes is all that someone needs. The other thing we really focused on, not only on my team but also within our network across the state, was working with local communities on steps they can take within their control and influence, knowing there was so much outside of our control.”

A big part of a Main Street director’s job is to cultivate relationships with business owners through face-to-face meetings. With those meetings sidelined, directors turned to video and phone calls with downtown building and business owners. Directors found they could make more connections over a few days than they had previously been able to make over weeks, Wagler says. While individual communities in Iowa suffered during the pandemic, overall “we saw a net gain of business in downtowns,” he adds.

Study methods

To conduct the study, Van Leuven focused on communities outside of metropolitan statistical areas — rural towns and villages likely to lie beyond the economic and cultural influence of a city. He explains in his paper, “The Impact of Main Street Revitalization on the Economic Vitality of Small-Town Business Districts,” that most of the programs are relatively small budget, compared with other economic development efforts, such as enterprise zones, which come with state or federal subsidies and tax credits.

Van Leuven used a difference-in-differences design, “an important tool to establish causality,” he says, to explore how Main Street programs affected economic growth. Difference-in-differences measure how the outcomes of two similar variables change when something happens to one of the variables.

Imagine a set of twins, Jan and Bob, competing to see who can take the most steps each week. Every Monday, they wake up refreshed from their weekend rest. Jan takes 10,000 steps while Bob takes 8,000 steps. After four weeks, a trend emerges: As the week wears on, the twins grow tired and they take 1,000 fewer steps per day. By Friday, Jan usually takes 6,000 steps while Bob takes 4,000 steps.

On the Sunday of the fifth week, Bob is frustrated that he keeps losing and gulps down an energy drink from a gas station. The drink promises to, “Give you a boost that’ll last.” Throughout the week he still feels more and more tired, but finds he is taking only 500 fewer steps per day. That Friday, he takes 6,000 steps, equaling Jan. Over the week, Bob has managed to close the gap a bit with his twin. The difference: He swigged an energy drink, Jan didn’t.

The Midwestern communities in Van Leuven’s study are like the twins. Those communities’ trends in job growth and business creation were roughly parallel at the start of the study period. At the end of the study period, the difference is that some of them adopted Main Street programs, others didn’t.

Van Leuven stresses his results should be interpreted with some nuance. It’s not that Main Street programs didn’t work in Michigan, Ohio and Wisconsin, but rather that towns in those states did not show major improvement for the two economic measures he tracked. He notes that apart from economic outcomes there are intangible social benefits a town can reap from a vibrant, walkable commercial center.

“It’s possible these new jobs downtown are coming from somewhere else within the town,” he says. “Downtown revitalization is not so much about growing the pie. It’s about redirecting economic vitality into the town center, which is traditionally a source of cultural identity.”

Expert Commentary