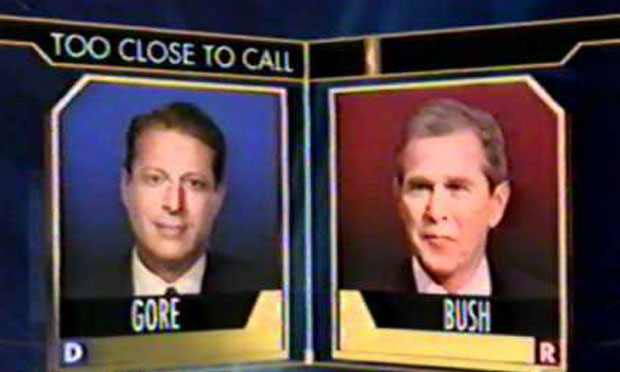

From the infamous 1948 “Dewey Defeats Truman” headline in the Chicago Tribune to the reporting debacle around the “Bush v. Gore” 2000 presidential election, news media have sometimes under-served the public on Election Day, sowing confusion and mistrust.

Many news outlets are getting better about providing nuanced election forecasts, and there are an increasing number of stories that dig into issues such as polling bias and statistical modeling. However, to truly improve Election Day coverage, more is needed. For decades, academics and media critics have noted a range of lamentable reporting habits, many of which have only been exacerbated by digital technologies. Further, there are now structural factors that have made reporting even more difficult — for example, the widening partisan gap between how citizens of different political persuasions view campaign coverage.

Despite this, Election Day and its immediate aftermath remain a unique opportunity for members of the media to distinguish themselves and educate the public about the process and substance of political campaigns.

Below are research-based suggestions on a range of issues that media confront on Election Day 2014, from good operating procedures to substantive policy issues around voting.

_______

Best practices for media — go beyond the numbers

Although political campaigns are changing in their cost, character, size and velocity, the fundamental aspects of elections are not. This means there are some cardinal rules journalists should adhere to, based on long experience and extensive research. The following rules were compiled by Thomas E. Patterson, Bradlee Professor of Government and the Press at Harvard:

- Encourage audiences to vote, and avoid discouraging them by falling into the “storyline trap.” Research indicates that media organizations are inconsistent in the way they encourage viewers to vote. It should be done consistently. This can mitigate the perennial charge that calling elections early serves to depress turnout in those areas where the polls are still open. Journalists should also avoid words that send potentially misleading signals that might influence viewers who have not yet voted. An example is the overuse of the word “expectations” to describe how a presidential candidate or political party is doing in states with early poll closings. Such language prematurely establishes a storyline or narrative. To say that a candidate or party is doing less well than was “expected” suggests underperformance.

- Explain exit polling to your audience. Early returns often are not indicative of final results. This is a chance to teach your audience about their state’s voting patterns (for example, the partisan leanings of certain counties or regions). Detailed explanations of exit polling should occur early in the election-night broadcasts and articles, and given audience turnover, these should be frequently repeated in abbreviated form.

- Stick to established guidelines for calling elections based on exit polls. Although different news organizations might reasonably establish different guidelines (for example, on whether to withhold a call until all the polls in a state have closed or whether to withhold it until all but a specified percentage have closed), a news organization should stick to its rules even if another news outlet calls the election. Of course, no news outlet wants to withhold a call that others have made, and every outlet likes to boast “you heard it here first.” However, there is little evidence that viewers are attuned to this competition.

- Use clear language that fits the numbers, and provide wider explanatory context. Calls based on exit polls, sample precincts, or partial returns are not definitive. They are properly described as “projected” or “estimated.” Further, viewers can be provided more numbers and shallower explanations or fewer numbers and fuller explanations, and audience research suggests that viewer interest and learning increase when the explanations are fuller. For example, don’t simply note the partisan gap between men and women but explain why the two groups diverge and also note that the difference is smaller in scale than, say, the gap between blacks and whites.

Hot topics, research angles and useful data for stories

Two trends in the 2014 midterm elections are noteworthy from the standpoint of media coverage: First, the massive infusion of money from third-party groups, enabled in part by the Citizens United Supreme Court decision; Second, the constant production of polling data of every sort. However, there are many other substantive items worth discussing during and after Election Day, as there are a wide variety of issues on the ballot across the 50 states. Beyond the Congressional contests, there are some intriguing state-level races, not only for governor’s seats, but for control of many state legislatures.

Below are topics and links to useful research:

- Money explained. As America continues to debate the role of money in politics, election night can be a crucial moment to educate the public about how campaign finance policy decisions are affecting elections and campaigns. The Wesleyan Media Project has compiled data on advertising dollars spent. While the full impact of the 2014 negative ad blitz will not be known for some time, it is worth citing the new research on the 2012 election cycle. Before attributing a sea change to a particular ad campaign, be aware that negative ads often matter only in limited ways and their effects are often short-lived. Correlation is not always causation.

- Changing nature of polling. The response rate to polls has greatly diminished over time, while many pollsters and analysts have also become much more sophisticated — and polls of all kinds are becoming more ubiquitous. What does this mean for democracy? The University of Michigan’s Michael W. Traugott has written about how the very meaning of the concept of “public opinion” is changing in an era of data aggregators. If trends accelerate, he asks, “will average citizens be the losers as news organizations devote an even greater proportion of their coverage to the relative standing of the candidates but include less explanatory information about where that support comes from and why it might be shifting during the campaign?”

- Voter and voting booth problems. Since 2000, there have been a number of efforts to reform the voting system to address everything from long lines to ensuring that every vote counts. Many of the proposed solutions are not new, but they often stall without enough political support. In January 2014, the Presidential Commission on Election Administration proposed a series of reforms. As problems inevitably arise again, it is worth pointing out some of the solutions currently proposed.

- Midterms and history. Historical data and perspective can help news audiences to understand the patterns that they are seeing. Midterm Congressional elections often follow a predictable pattern (though not always). So is this a referendum on the President? Be careful. It is worth noting that research has examined the last midterm — in 2010 when the Tea Party first surged — and concluded that it is not sufficient to say the election was a “referendum” on President Obama. A team of Duke University political scientists note that, crucially, voters who blame both parties may go decisively for the party out of presidential power.

- New campaign tactics enabled by technology. As reporters explore why campaigns succeeded or failed, it is worth paying attention to new trends in field tactics, particularly around what is being called “computational management.” There is also intriguing new research about which get-out-the-vote strategies work best, particularly in low-turnout areas. Which strategies were employed in your local community?

- Voter ID laws and voting restrictions. These are the subject of continuing controversy in U.S. elections, and research on their impact is evolving. A new study by the nonpartisan federal Government Accountability Office summarizes the latest data. It can help to anchor media discussions. There have also been numerous case studies analyzing voting rule changes in key states such as Florida.

- Ballot questions and wording. It is well worth telling viewers exactly how ballot questions were posed and how that precise wording was arrived at. Research shows that “framing” matters, and can shift voters’ perceptions on the issues.

- Don’t forget the issues. The traditional critique of campaign coverage is that it focuses on the “horse race,” or process, not on the issues, or substance. While it’s inevitable that winners and losers will be the focus on Election night, think about using the moments in between updating electoral results to look at the issues at stake. This may be easiest around state ballot initiatives, which this year focus on everything from marijuana use and abortion to minimum wage increases and gambling. Use the moment of mass attention to educate.

Keywords: mid-term elections, polarization, press, polling, Election Day, Congress, Senate, local reporting

Expert Commentary