On October 5, 2013, American commandos raided a base of the Islamic militant group al-Shabab in southern Somalia. According to media reports, the target was Abdulkadir Mohamed Abdulkadir, known as “Ikrimah” (or Ikrima), a commander said to be responsible for planning terrorist actions outside the country’s borders. The raid came two weeks after al-Shabab gunmen took over Nairobi’s Westgate Mall, killing 67 people and causing more than 100 injuries. The attack was only the latest for the group, which has a relatively brief but bloody history.

While al-Qaeda’s origins date back to the late 1980s, al-Shabab emerged in the mid-2000s. According to a 2009 paper in Middle East Quarterly by Daveed Gartenstein-Ross “The Strategic Challenge of Somalia’s Al-Shabab,” the militant group “rose from obscurity to international prominence in less than two years.” An outgrowth of the Islamic Union (IU) and Islamic Courts Union (ICU), both militant groups, al-Shabab split away in 2007. Unlike the IU and ICU, whose primary goals were to control Somalia and nearby ethnic Somali areas, al-Shabab had a global jihadist ideology. The group proclaimed its allegiance to al-Qaeda early on, with al-Qaeda only reciprocating later. The U.S. government declared al-Shabab to be a terrorist organization in 2008.

A 2012 article in Politics, Religion & Ideology by Oscar Gakuo Mwangi of the University of Lesotho, “State Collapse, Al-Shabab, Islamism, and Legitimacy in Somalia,” provides a useful overview of political Islam and the nature of failed states. While Somalia is 98% Muslim, religion was long an essential part of life but didn’t trump clan identity. Mwangi details how al-Shabab capitalized on Islam as a common identifier to become a serious force in Somalia.

According to a 2013 report by the University of Maryland’s National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START), since 2007 al-Shabab has “carried out nearly 550 terrorist attacks, killing more than 1,600 and wounding more than 2,100. The number of attacks attributed to al-Shabaab has increased rapidly from less than 10 in 2007 to more than 200 in 2012.” For example, in 2010 the group bombed a café in Kampala, killing more than 70 Ugandans who were gathered to watch the World Cup. The assault on the Westgate Mall was atypical for the group: It was their only known “hostage-barricade attack,” where victims are taken hostage rather than kidnapped. The longer the standoff, the longer the attention of the world community can be held — and the Westgate attack lasted four days.

Al-Shabab has also distinguished itself through its use of new media. According to a January 2013 START report, the group has been using Twitter since December 2011 to engage with English-speaking supporters. “At the time of this brief’s publication, the organization (@HSMPress) had more than 20,000 followers and had tweeted approximately 1,250 times, before its English-language account was suspended by Twitter Jan. 25, 2013.” In its tweets, the group is most concerned with promoting its version of events — that Somalia is under siege in the war on Islam.

Jonathan Masters’s September 2013 article for the Council on Foreign Relations, “Al-Shabab,” reviews information on al-Shabab’s origins, turning points in the group’s history, leadership and sources of funding:

Counterterrorism experts say al-Shabab has benefited from several different sources of income over the years, including revenue from other terrorist groups, state sponsors, the Somali diaspora, charities, piracy, kidnapping, and the extortion of local businesses. Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Syria, Iran, Qatar, and Eritrea have been cited as prominent state backers — although most of these governments officially deny these claims.

In 2008 al-Shabab seized the southern port city of Kismayo and used it as a base for an illicit trade in charcoal, earning the group $35 to $50 million a year, the CFR estimates. Al-Shabab’s control of the port has fluctuated — it was forced to retreat in September 2012 — but the group regained access to the charcoal trade this year. Al-Shabab also has a role in the illegal importation of sugar to Kenya, a trade worth hundreds of thousands of dollars, according to the United Nations.

Despite the publicity gained by the Westgate Mall attack, al-Shabab has seen its fortunes suffer since 2011, according an August 2013 brief, “Somalia’s Al-Shabaab: Down But Not Out,” by George Washington University’s Homeland Security Policy Institute:

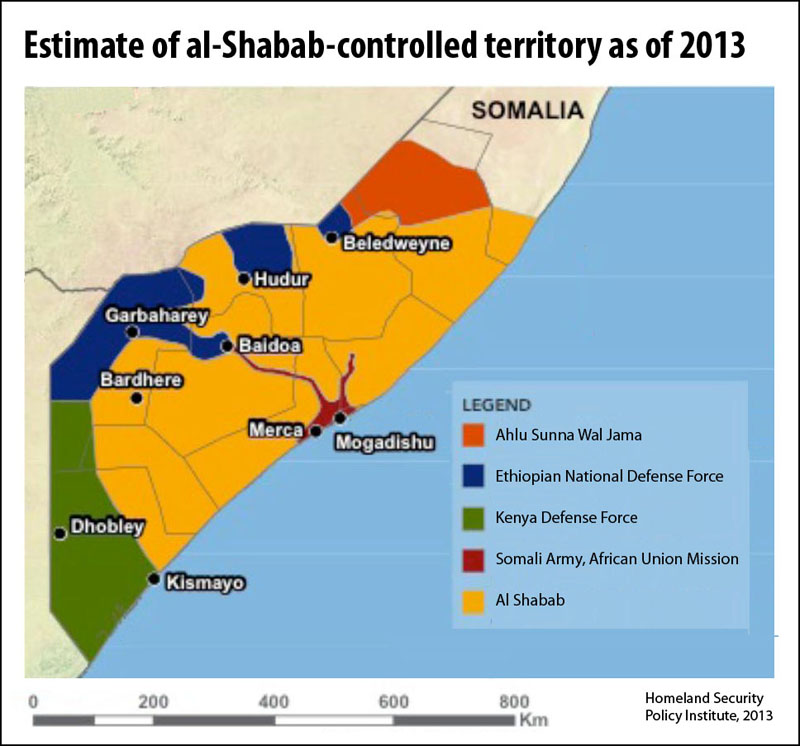

A three-pronged offensive led by government-allied African Union Mission to Somalia (AMISOM), Kenyan and Ethiopian forces, combined with a famine in south and central Somalia, forced al-Shabaab to withdraw from Mogadishu and reassess its strategy. Over the next year, internal divisions, a loss of public support and continued offensives by government-allied forces throughout the country significantly weakened the group. Although al-Shabaab remains a major threat to security in Somalia today, the group’s resources, territory and influence have diminished significantly.

The report also highlights al-Shabab’s internal strife, which has extracted a considerable toll. As the territory controlled by the group shrinks, issues such as strategy, treatment of foreign fighters, tactics and the long-term goal have become even more contentious. Some leaders and factions remain committed to a globalist mission — the unification of all Muslims under a single Islamic state — while others push for a nationalist agenda.

“Despite its setbacks, al-Shabaab still commands territory and fighters,” the report concludes. The group “remains a serious threat capable of destabilizing Somalia and the greater Horn of Africa region, and potentially inspiring attacks globally.”

Keywords: terrorism, Africa

Expert Commentary