“In some respects, there was nothing unusual about the killing of Walter Gonzalez.

Eighty-six pedestrians had already died in car crashes in New York City last year by October 23, when a driver slammed a pick-up truck into Gonzalez in Brooklyn. It was not out of the ordinary that the driver was speeding, nor that his license had been revoked months prior.

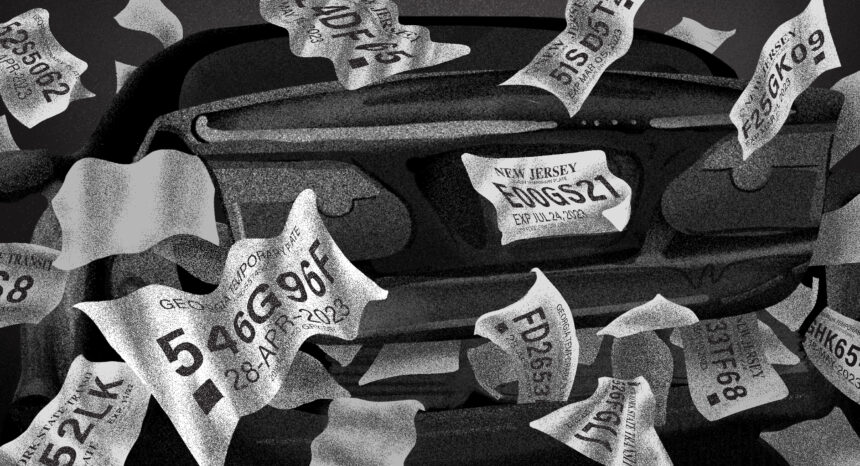

But there was one thing that stood out about the crash: the paper license plate hanging from the back of the truck.”

-The lede to “Ghost Tags: Inside New York City’s Black Market for Temporary License Plates,” by Jesse Coburn

In April 2023, online news outlet Streetsblog NYC published the first story in a four-part investigation exposing a vast black market for temporary license plate tags, the massive scale of which was not publicly known.

Temporary tags are legal when someone buys a car. In New Jersey, for example, a dealer issues the buyer weatherized paper tags to display until metal plates come in the mail.

But it is illegal for dealers to issue temporary tags absent a car sale. It is also remarkably easy for dealers to sell those tags on the black market. And when dealers were caught, the penalties were small — before the series from Streetsblog investigative reporter Jesse Coburn.

More than 100 dealers in Georgia and New Jersey who authorities found violating regulations “have printed more than 275,000 temp tags since 2019,” Coburn writes, while tags from New Jersey dealers “are among the most common on the streets of New York City, as are tags from Georgia and Texas.”

Temporary tags proliferated during the COVID-19 pandemic, when state motor vehicle departments across the country were shut down. People buying cars privately had difficulty getting their vehicles registered. Some private buyers turned to used car dealers for temporary tags.

“Some New York City blocks suddenly seemed to be full of cars with out-of-state temps,” Coburn writes. “They started popping up in crimes across the city, like a shooting in Brooklyn, a robbery in Manhattan and a hit-and-run in the Bronx in which a driver plowed into a family of six on the sidewalk.”

Further, “Drivers were using them to mask their identities while evading tolls and traffic cameras, or while committing more serious crimes, authorities said,” Coburn writes.

At the time the Streetsblog investigation was published, auto dealers fraudulently selling authentic tags could fetch $100 to $200 apiece, while the maximum violation for a first-time offense in New Jersey was $500, Coburn found. One dealer in New Jersey issued tens of thousands of tags in 2021, and “could have made millions of dollars,” if all those were sold on the black market, Coburn writes.

Coburn’s seven-month investigation was built upon nearly 50 public records requests he filed, particularly from motor vehicle authorities in New Jersey and Georgia, for information on dealers illegally issuing temporary tags. Those tags, Coburn found, were being issued by dealers who appeared by and large not to be engaged in any legitimate business.

“The data really tells the story because it’s like, here’s this dealership that has no online presence, none whatever, no listing on Google Maps — none of the trappings of a successful car dealership — issuing tens of thousands of temp tags every year,” Coburn says.

Since the Streetsblog series, New Jersey has imposed tougher restrictions on temporary tags, including potential prison time and fines up to $10,000 for violators. A lawmaker in Georgia has also introduced legislation aimed at curtailing the market for fraudulent temporary tags there.

“New Jersey and Georgia have also shut down dozens of dealers for temp tag fraud since the series came out and proposed $150,000 in fines,” Coburn says. “Seven of the dealers that I sort of flagged to these states as possible temp tag violators are now under criminal investigation.”

Keep reading for four tips from Coburn based on his investigation, including how it came about, how he got people buying and selling temporary tags to talk to him, and the types of sources he thinks are most compelling.

1. Stay alert — is there something weird in your neighborhood?

Being an investigative reporter isn’t necessarily about having deep government sources or getting your hands on an incendiary tip, Coburn says. Sometimes, a strong investigation can come from staying alert to changes in the places you frequent.

“During the pandemic, in my neighborhood in Brooklyn, I started seeing tons of these paper license plates on cars from out of state — Texas, New Jersey, Georgia, Virginia, Maryland,” Coburn says. “And, you know, I’m sort of wondering what this is about.”

Coburn says he saw some local news coverage of illicit temporary tags in New York City, but those stories were driven mostly by police reports and press conferences.

“It just seemed inconceivable to me that so many people had just bought cars in Texas or Georgia,” he adds.

So, he began filing public records requests for data on temporary tags issued by auto dealers in New Jersey.

“What I saw was that there were these dealerships that were issuing massive numbers of tags — 10, 20,000 tags in a single year,” Coburn says. “Which should mean that that dealership is selling that many cars.”

He started digging into one dealer, F&J Auto Mall in Bridgeton, New Jersey, and learned it “issued 36,000 temporary license plates in 2021 — more than any other dealership in the state, including the used-car juggernauts Carvana and CarMax combined,” Coburn writes in Part 1 of the series.

Coburn recalls that when he looked up the publicly available address for F&J, Google Maps images showed a “warehouse in the middle of nowhere, with no big sign out front. A giant parking lot that was totally empty. That was the moment I was like, ‘There’s something really crazy going on here.’”

2. To ‘find your Virgil,’ try old-fashioned cold calling.

Cold calling may not feel like the most natural thing in the world, but if you don’t otherwise have good sources for your story, a few dozen unsolicited calls can work.

That’s what Coburn did when he realized he needed reputable auto dealers to walk him through what the data indicated about F&J. He searched for dealerships in northern New Jersey, close enough to his home base to potentially visit in person.

Initially, the response from auto dealers was “chilly” and “people were very skittish,” Coburn says. But before long, he struck journalistic gold.

“It took me about a dozen dealerships,” he says. “But, eventually, I got this guy on the phone named Abdul Cummings.”

As an émigré from Palestine running a legitimate used auto dealership, Cummings was troubled by the illegal activity happening in his industry, Coburn says. Cummings immediately began describing to Coburn how the paper tag fraud worked. Coburn recalls that Cummings was “very candid, and smart” with “a lot of integrity.”

“Find your Virgil,” Coburn advises, referring to the ancient Roman poet, a fictional version of whom shepherds Dante through hell in the Divine Comedy. “Someone who can kind of guide you through.”

Coburn found many other key sources through cold calls, such as Jose Cordero, who told Coburn he made $18,200 selling temporary tags before New Jersey authorities caught him.

3. Use court calendars to find sources involved in active cases.

Coburn identified temporary tag buyers through cold calls, but also by looking at WebCriminal, the online criminal court portal for New York.

“It’s extremely Web 1.0 — it’s very hard to use,” Coburn says. “But there is a wealth of information if you kind of know how to find it. And so eventually, I figured out how to search the court calendars for every day, and to search by violation.”

The violation for possessing illegal temporary tags is called “criminal possession of a forged instrument.” Coburn would search for people being arraigned on that charge and potentially related charges, such as driving with a suspended license.

“I would just sit in court and wait for their hearing to be called,” he says. “You know, I just had this list of names. And then after they were arraigned, I approached them and tried to talk to them — and was once again amazed at how candid people were.”

That’s how Coburn got the story of Adrian Mocha, who had his license suspended. In the span of one year, Mocha went through “eight or nine” temporary tags, according to Part 3 of the investigation. Coburn simply approached Mocha and interviewed him following one of Mocha’s court dates.

4. Seek sources outside the spotlight for interesting anecdotes.

Politicians and other high-profile officials are often used to interacting with members of the news media. They may be guarded and self-aware in what they publicly convey. But people who have less or no experience talking with reporters provided some of the more interesting details in Coburn’s story — such as Ali Ahmed, manager at Zack Auto Sales, which is registered in New Jersey, according to Coburn’s reporting.

Coburn visited Zack Auto Sales and asked Ahmed about the 999 temporary tags the dealership issued in 2022, despite having no presence online. Ahmed said, “If you’re going to go deep, and I find it, and you go to ask about my company in Trenton and New Jersey, you’re going to get trouble with it, believe me,” Coburn writes in Part 2 of the series. Ahmed said they “retail and wholesale [cars] online, like a broker,” according to Coburn’s reporting.

“Streetsblog did not find evidence that Zack Auto Sales illegally sells temporary license plates,” Coburn writes. “But one car wholesaler and one car broker based in New Jersey told Streetsblog that wholesalers and brokers have no reason to issue large numbers of temp tags.”

Coburn also recalls the compelling story of how Kareem Ulloa-Alvarado discovered he had been unknowingly delivering temporary tags for a dealership for a few weeks in December 2022 and January 2023, after finding the gig on Craigslist.

In Part 4 of the series, Coburn reports that Ulloa-Alvarado didn’t realize he was doing anything illegal until he was attacked at knifepoint during a delivery in the Bronx. When he went to police, a detective told Ulloa-Alvarado that he could be arrested for delivering fake tags if he filed a report about the assault. “Kareem was shocked,” Coburn writes.

“They were very interesting, original people,” he says. “I like stories where I’m not just speaking to media-trained government officials.”

Read the stories

‘Duped’: A Harlem 20-Something Blows the Whistle on an Illegal Temporary License Plate Business

Expert Commentary