Police chases, often initiated over a minor crime or none at all, kill nearly two people a day across the U.S., “and public officials are failing at nearly every level to confront the growing problem,” reporters Jennifer Gollan and Susie Neilson write in the February 2024 opening of their investigative series in the San Francisco Chronicle.

Gollan and Neilson identified at least 3,336 people killed resulting from police vehicular pursuits in the U.S. from 2017 to 2022, based on a database the reporters created, which they say is the fullest national accounting of police chase related fatalities — and which is publicly available on GitHub.

“There’s no real national standard for how police have to report these deaths,” Neilson says. “And so, even our data set is likely an undercount of pursuit deaths, just because not every pursuit either has a news story written about it, a court case filed about it, or the police department has reported it.”

Those police chases don’t just kill suspects being chased or, in rare instances, officers. From 2017 to 2022, at least 551 bystanders were also killed, the reporters found.

Black people are disproportionately affected, accounting for 25% of bystander deaths, they discovered, despite making up 13% of the national population.

“Deadly police pursuits are much more likely to occur in majority Black neighborhoods, raising questions about the consequences of aggressive policing in these areas, and how one of the most dangerous tactics in law enforcement is deployed in these places,” the reporters write.

Department rules about initiating chases are “often permissive” and “vary by department,” Gollan and Neilson found. While law enforcement officers can be criminally charged for reckless chases, district attorneys do not often bring charges and officers rarely face internal discipline, according to the investigation.

“[Sources] said at the beginning of the project that police were never held accountable for dangerous chases,” Gollan says. “And so, we really wanted to quantify in just how many cases were officers actually convicted or faced any sort of consequences.”

Through interviews, court documents, and police records, Gollan and Neilson found 140 officers who appeared to have broken the law or violated agency policy, such as by driving recklessly or not turning on their lights and sirens during a chase.

“Just six have been convicted of criminal charges,” they write. “Another five face pending charges. And a local prosecutor is reviewing the cases of two others.”

Lawsuits brought following injuries or deaths resulting from police chases hurt taxpayers, the reporters found, with $82 million in payouts from local governments and insurers since 2017.

“This is likely a significant undercount, given that some local governments refused to release key data — or said they didn’t track it,” Gollan and Neilson write.

Federal and state lawmakers, along with academic scholars, responded swiftly to the investigation. Dozens of local newsrooms used the database Gollan and Neilson created to do their own police chase stories.

- U.S. Reps. Mark DeSaulnier and Eleanor Holmes Norton called for a national police chase fatality database in a November 2024 letter to then-Attorney General Merrick Garland and the heads of the Bureau of Justice Statistics and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, writing that “We cannot fix or prevent deaths when the data is not an accurate reflection of what is happening.”

- The Policing Project at the New York University School of Law, an organization founded in 2015 that focuses on police accountability, developed a model federal statute with guidelines for police vehicle pursuits.

- The day after the first story published, Washington state lawmakers cited the investigation during a joint committee hearing where the senior counsel at the Policing Project also testified and cited the investigation.

- At least 75 newsrooms, including from California, Connecticut, New York, Minnesota, Michigan, South Carolina and Texas, published their own stories about police pursuits, based on or citing the data Gollan and Neilson gathered.

- Researchers from the NYU School of Global Public Health published a paper, based on the data the reporters compiled, in the Journal of the American Medical Association in November 2024.

Keep reading for five reporting tips culled from a recent Journalist’s Resource interview with Gollan and Neilson, with insights on interviewing trauma survivors, building a database from scratch and finding success with public records requests.

1. Consult experts before creating a database from scratch.

Before embarking on the massive undertaking of compiling a national database of police chase fatalities, the reporters talked with data experts — a crucial step that helped them identify reasonable goals and how to structure the database.

“We talked to statisticians,” Neilson says. “We talked to criminologists. I spoke with multiple data journalists who had built databases before on police-related violence issues.”

After that, Gollan examined what data was already out there.

She particularly looked for police chases captured in Fatal Encounters, a project that aims to record all police-related incidents resulting in a fatality in the U.S. since 2000, maintained by journalist D. Brian Burghart.

Gollan and Neilson merged that information with incomplete data from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, local news stories, court records, and public records requests. They used R, a programming language used for data analysis, to build the database.

“That’s the coding language I know,” Neilson says. “It’s a tool used by many data reporters to kind of work really big data sets.”

2. Find common ground and don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good when it comes to public records.

Throughout the investigation, the reporters filed more than 250 public records requests to law enforcement agencies and local prosecutor’s offices, Gollan estimates. They ultimately obtained disciplinary information on 74 officers involved in fatal police chases. This information was a central part of the investigation.

“We wanted to build out the accountability side,” Gollan says.

The reporters needed to make multiple records requests in several instances, and many agencies asked why the public records were needed, even though requesters don’t typically have to give a reason (though that may vary based on state law).

Gollan says she’d often hop on a call with a public records officer or police officer in charge of public records to talk through their reservations in providing the information and explain where she was coming from.

“Find a way to establish trust with them, that you’re both working for the public good,” she says. And think broadly, she adds: Public records requests don’t have to just be made for written documents. You can also request video and audio. Doing that turned the investigation into much more of a multimedia project, Gollan says.

For the police accountability portion of the investigation, Gollan and Neilson retrieved enough records to offer the public incomplete but valuable insight into how often officers were disciplined or faced criminal charges for their roles in fatal chases.

“Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good,” Gollan says.

3. Ask for the lowest acceptable rate for public records.

When making dozens or hundreds of public records requests, you’re likely to come across agencies that demand unreasonably high fees in exchange for the records. Think of this not as an insurmountable obstacle, but the opening salvo in a negotiation.

“We pushed back firmly and politely on estimates that were exorbitant,” Gollan says.

Start by asking the agency to itemize the costs for each portion of the work to retrieve the records, including the person doing the work, their job title and pay rate. Also confirm that they’re calculating costs for electronic records — not a huge stack of paper, if paper records aren’t necessary for your investigation.

“One thing Jennifer taught me that I thought was really smart is when you push back on some of these costs, you want to confirm that the hourly rate for labor is the lowest acceptable rate — the amount it would cost the lowest paid person to produce the records,” Neilson says.

4. Establish shared goals and interview parameters with trauma survivors.

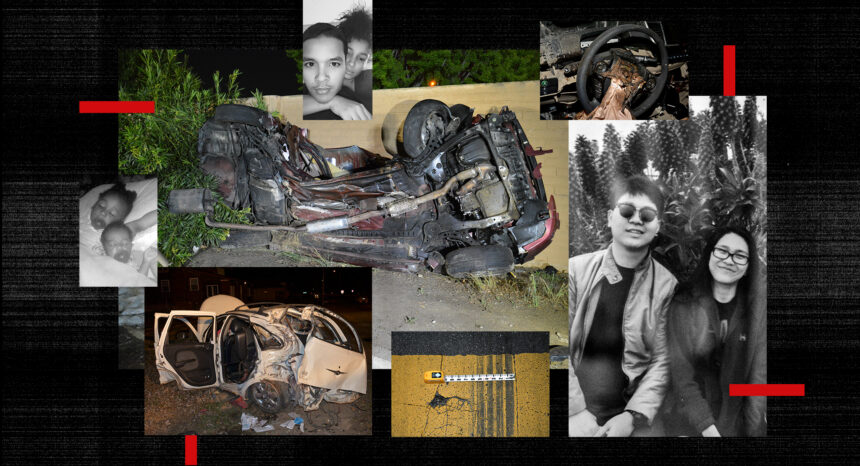

While interviewing Janae Carter, who lost her two small children and partner when their car was hit by a suspect being chased by police, Gollan recalls Carter’s mother and attorney were also on the call. Their presence made Carter more comfortable while recounting one of the worst events of her life.

In addition to making concessions like having other family members present during an interview, helping sources who have survived trauma understand your reporting goals can help build trust. That can include sharing topline findings from your investigation so far.

“In some cases, it motivated people to recount these traumatic experiences because they had a shared purpose with us, which was bringing these dangerous chases to light,” Gollan says.

Also, as other Goldsmith Award finalists have noted, giving survivors agency over an interview can help them feel safe to tell their stories.

Gollan says she might have had some specific information in mind she wanted to gather going into an interview with survivors or family members, but she “often let the conversation take its own course.”

“And they often cover that material in the course of sharing the information that they feel comfortable with,” she says.

5. Seek written consent from survivors.

In addition to explaining that their stories would appear in the Chronicle, the reporters explained to survivors and surviving family members exactly where within the investigation their recollections would appear. For example, the reporters told the father of Precious and Philip Nievas that his children’s deaths would lead the series.

That lede included a graphic video the reporters obtained of the aftermath of the chase that killed the Nievas children, whose car was struck while turning through an intersection by a suspect police were chasing.

Gollan recommends a practice the Chronicle follows: obtaining written consent from survivors or surviving family members before publishing graphic videos or retelling traumatic events. Consent doesn’t need to be given in a formal document — the reporters used text messages to obtain consent, Gollan says.

“It’s something both for the paper, the Chronicle, but also for them, so that they’re prepared and understand and have an opportunity to say, ‘I’m just not comfortable with that,’” she adds.

6. Conduct interviews in person, if possible.

When sources are open to meeting in person, do it if you can — if your newsroom has the resources for travel. Neilson recalls interviewing the family of Trevon Mitchell, including his grandmother Danita, in Louisville, Kentucky.

Mitchell was a bystander during a July 2021 police chase some two miles west of downtown, spurred by a driver who failed to use a turn signal. “This is where a driver who was fleeing police struck Trevon Mitchell,” write Neilson and Gollan. Mitchell, riding a moped, was severely injured. He later died at a hospital.

“Danita Mitchell wears a heart-shaped necklace bearing her grandson’s fingerprint,” the reporters recount in their investigation. It’s a detail that might not have come to light during a phone interview, Neilson says.

“Having the ability to actually go out and lock eyes with Danita, talk to her really in-depth about her experience, made our reporting more immediate and powerful,” Neilson says.

Read the stories

Police chases are killing more and more Americans. With lax rules, it’s no accident.

Thrown from his moped by a car fleeing police: One man’s death reflects a shocking disparity.

Key takeaways from a San Francisco Chronicle investigation of deadly police pursuits.

How the Chronicle built a national database of fatal police chases.

Expert Commentary