Medicare paid health insurers roughly $50 billion from 2018 to 2021 for diagnoses for which “patients received no treatment, or that contradicted their doctors’ views,” write a Wall Street Journal reporting team in the July 2024 opening to their monthslong investigative series.

Those diagnoses were made by the insurers, rather than doctors. Some of the diagnoses, such as diabetic cataracts, could net insurers thousands of dollars per year per patient, according to the investigation.

The reporters, Christopher Weaver, Tom McGinty, Anna Wilde Mathews and Mark Maremont — with graphics by Andrew Mollica — analyzed 1.6 billion diagnoses using Medicare Advantage data in a rarely seen data-use agreement between a news organization and the federal government.

“The data was revealing in that it surprised us in some cases by the magnitude of some of the things that we found,” Weaver says. “Just the amount of dollars going out the door to pay insurers for diagnoses that didn’t appear to be getting treated.”

Medicare Advantage, created in 1997, is a “$450-billion-a-year system in which private insurers oversee Medicare benefits,” the reporters write, that “grew out of the idea that the private sector could provide healthcare more economically.”

Today, half of the 67 million seniors and people with disabilities who participate in Medicare get coverage through Medicare Advantage, according to the investigation.

“One reason is that insurers can add diagnoses to ones that patients’ own doctors submit,” the reporters write. “Medicare gave insurers that option so they could catch conditions that doctors neglected to record.”

To access this vast repository of Medicare data, the reporters had to think like academic researchers. The data was subject to a data use agreement, meaning it included personal health information or personally identifiable information. The data specifically included information about doctor visits, hospital stays and prescriptions, but not patient names.

“It’s difficult to overstate how large and complicated this data set is,” Maremont says. “You’re talking about every encounter, every doctor visit, every hospital visit, every drug, everything else over a four-year period. And there’s thousands of fields in this data.”

The reporters submitted a hypothesis and described to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services how they would use the data. The process even involved justifying to the federal government why individual rows of data were needed for the investigation.

“It was a lot of back and forth with [the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services] and their contractor about, how can we slightly tweak the data-use agreement to comply but also fit our needs,” Maremont says of the nine-month timeline to access the data.

Initially, the government was willing to provide the reporters the data access they wanted — with the caveat that they could not write about any individuals in the data, McGinty recalls. The team explained they would not use the data to identify individuals, but that they certainly would be talking with people in the database who they had identified through other reporting means. The government agreed to those terms.

“You don’t always know where the story is going to take you, so we needed a degree of flexibility that would allow us to do what we needed to do as reporters,” Weaver says. “Working that out was, I think, certainly novel for us, and I think for them as well.”

“It was a heroic effort, mostly by Tom and Chris to get this thing through to the finish line,” Maremont says.

“It felt a little bit like the dog that caught the car,” McGinty adds.

Government officials and health insurance providers responded swiftly to the investigation.

- The Office of Inspector General for the Department of Health and Human Services recommended that Medicare stop paying insurers for diagnoses resulting from home nurse visits initiated by insurers.

- The Congressional Budget Office estimated that cutting off Medicare Advantage payments based on home visit diagnoses would save $124 billion over a decade.

- A subcommittee of the House Ways and Means Committee interviewed witnesses about the Journal’s findings.

- One medical group in Florida self-reported itself for improper payments to UnitedHealth Group.

- The health-policy nonprofit KFF cited the Journal’s investigation in their analysis of how patients were fleeing Medicare Advantage for traditional Medicare in large part because they were being denied coverage for nursing home expenses.

Keep reading for four reporting tips culled from a recent Journalist’s Resource interview with several members of the Journal’s investigative team, including about taking notes during data analysis, using AI for coding and being persistent when seeking sources.

1. Take detailed notes when querying databases.

“The way you usually work with data is, you’re exploring a dataset, you have a thesis,” McGinty says. “You ask some questions, those answers that you get back with your queries raise more questions, you go ask those.”

At any given time, the reporting team was mining the data looking for answers to several different questions, and queries might take hours to complete because the database was so large, McGinty says.

When shifting gears between queries and generally dealing with such a complex database, making notes along the way is “vital, vital, vital,” he says.

“My tendency is, I’m excited to get the answer, so I’ll charge ahead and not be notating enough,” McGinty says. “Then you go back and go, ‘Wait, why did we do this thing here? I forgot about it.’ So, you really have to document every step of the way with a paper trail for your future self that won’t remember what you’ve done.”

McGinty makes notes in Microsoft Word documents, and also annotates within the coding script he’s working with, to describe the steps used to create specific lines or chunks of code and why. This can also be useful for reporters in explaining how and why certain conclusions were reached to editors who may not understand coding and large data analysis.

2. Tap into AI to unlock unfamiliar programming languages.

McGinty had a lot of coding experience going into the project. He’s very familiar with R, a programming language used by many data journalists.

But, when the team got access to the Medicare data, a different programming language, SAS, was only option to analyze the data through the government-run platform.

McGinty used ChatGPT, not to learn SAS from scratch, but as a shortcut to translate particular functions he knew would work in R into SAS.

“Chat GPT turned out to be a huge savior in that regard,” he says. “It’s really good for coding.”

3. Exercise persistence when seeking difficult-to-find sources — and use audience feedback boxes.

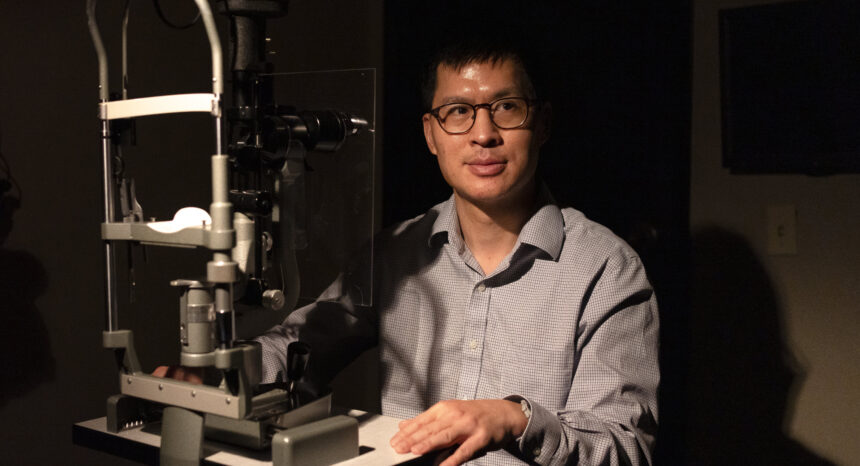

Doctors such as Howard Chen, an ophthalmologist in Goodyear, Arizona, represented the perspective of medical professionals with patients who insurers had diagnosed.

“Insurers added diabetic cataract diagnoses to 148 patients treated by [Chen],” the reporters wrote. “He said he saw at most one or two such cases a year.”

Sheer persistence was the key to finding doctors like Chen.

“That was an exercise in just brute force,” which included Maremont and Wilde Mathews, Weaver says. “I myself counted up to 75 doctors that I contacted basically to ask the question, ‘Have you seen patients come in with these home visit reports that listed diagnoses that you had suspicions about or thought were inaccurate?’”

Military veterans were another important group the reporters contacted. In a follow-up story, the reporters covered how Medicare Advantage insurers were reaping billions of dollars a year to cover veterans, many of whom already had health coverage through the Veterans Affairs system.

“I was literally calling VA halls around the country,” Maremont says. “I talked to private caregiver people who help veterans enroll on plans. I talked to insurance brokers. I talked to all sorts of people and we eventually found a number of veterans who kind of fit, were enrolled in both, who would talk to us.”

But the first story in the series included a feedback box encouraging readers to contact the reporters, which helped accelerate the process of finding sources. The responses populated into a spreadsheet and gave reporters a ready-made list of nurses, doctors and patients to follow up with.

“Compared to the first story, where you’re calling dozens and dozens of people looking for people who have had like a needle in a haystack type experience, [the feedback box] generated a very reliable source of people who had the kinds of experiences that we were looking to explore,” Weaver says.

4. Consider using a ‘no surprises’ framework before publishing.

After analyzing hugely complex datasets and coming up with findings that could affect specific companies, give those companies a chance to respond with a detailed explanation “to kind of poke and prod” your work, Weaver says.

For the first story in the series, McGinty recalls that the team sent a 12-page methodology to the companies that could have been most affected by their reporting — including UnitedHealth. The methodology served as a step-by-step guide for what the team had uncovered and how they did so.

“The Journal has this policy that, really most newspapers do, but at the Journal it’s very specific, called a ‘no surprises policy,’” McGinty says. “So, if you’re going to write something about somebody, they’re going to know exactly what you’re going to say.”

A UnitedHealth spokesperson called the Journal’s analysis “inaccurate and biased,” as reported in the series. The reporters, for their part, noted that “The Journal consulted more than a dozen experts, including academics, actuaries and policy analysts, about its analysis of the Medicare data, who said the methodology was sound.”

Meanwhile, other companies put the reporters on the phone with staff who work on the Medicare topics the reporters were investigating. Some of those staff raised “objections that we were able to consider and, in some cases, address by changing our analysis,” Weaver says. “In many cases, they sort of just kind of acknowledged our findings.”

Read the stories

Insurers Pocketed $50 Billion From Medicare for Diseases No Doctor Treated

The Sickest Patients Are Fleeing Private Medicare Plans — Costing Taxpayers Billions

UnitedHealth’s Army of Doctors Helped It Collect Billions More From Medicare

The One-Hour Nurse Visits That Let Insurers Collect $15 Billion From Medicare

Insurers Collected Billions From Medicare for Veterans Who Cost Them Almost Nothing

Expert Commentary