CBS News Prime Time Anchor John Dickerson, who has covered eight presidential candidates in his career as a political journalist, gave the Theodore H. White Lecture on Press and Politics at Harvard Kennedy School on Feb. 5. He was introduced by his former colleague Nancy Gibbs, director of the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy and the Edward R. Murrow Professor of Practice of Press, Politics and Public Policy at Harvard Kennedy School. Dickerson and Gibbs worked together at Time magazine. The following is a lightly edited version of Dickerson’s speech, along with a video of the event.

Hello everyone. It is a great honor to be with you all tonight for this maiden voyage of giving a speech using an iPad. If something goes wrong with the speech, it’s the technology’s fault.

You have been in my head the last month as I worked on this, which is a gift. I’m grateful for your attention and for the prompt to think more deeply about this topic.

Thank you, Nancy. I am here because of Nancy — not just because she invited me, but I am at this point in my career a beneficiary of her expertise. We worked together at Time, which, as I tell my college-age kids, is what’s known as a weekly news magazine.

You are lucky if, whatever your craft, you get to watch the best in your business at close range.

I was a reporter in the Time system, which meant I traveled with the [political] candidates and sent dispatches back to Nancy, who wrote what people would read. I’d send in a shaggy mutt from the road and she’d shave it down into some magnificent Weimaraner — scope, context, genius for detail, a compelling story. Most important, Nancy taught me the value of treating colleagues’ work with generosity, inspiring me to strive for the same standard.

At Time, we’d start stories with a theatrical lede to set the scene. Sometimes, writers would force the moment a little. Sweeping revelations came in scenic settings. Turning points hovered over evocative food: Candidate Clinton set down his Dunkin Donuts cup and set his jaw.

That kind of thing.

But I swear I am not torturing the facts when I say Nancy was there for the scene that I would make the theatrical lede of this talk.

In 2004, while in Crawford, Texas interviewing the incumbent President George W. Bush for Time. He was running against John Kerry. We stood in his driveway post-interview. Bush said when we interviewed John Kerry we should ask him how he makes decisions. “That’s all this job is about,” he said.

This struck me. Not that the presidency is about decisions. I’d covered the Bush White House and Clinton White House. What struck me was how little we talked about the actual job of being president when we covered campaigns. As a campaign reporter, I covered tactics, polling, battleground states. But not the job itself. Nancy thought about that stuff, but for me that moment with Bush in 2004 was a turning point.

So we’re going to start in that driveway tonight as I think through, with your help, how the press is helping the American people pick a person for a very specific job at a very dangerous time and how we can do better. And when I say “we” every time tonight about the press, I’m referring to myself as much as anyone.

I apologize if I talk too fast. But I don’t want to go on so long and be accused of what they used to say about Senator, Vice President and candidate Hubert Humphrey, who went on too long.

What follows a Humphrey dinner speech? Breakfast.

My argument is that our coverage of the presidential campaign is too distant from the office of the presidency.

At the moment, the horse race gets the attention — who is up and who is down — which makes my argument obtuse. With that in mind, I would like to give you a schema for my talk tonight:

Our first picture, please.

What you see here is a horse race. The man standing in the middle of it while it rages past him illustrates what it’s like to do this — try to pause the horse race and take an approach that keeps the duties of the presidency in mind.

However, we will soldier on.

First Principles

Let’s start with first principles.

What is our role covering presidential campaigns? To provide useful information to voters so they can make informed choices in picking the person who will affect their lives.

More briefly, presidential campaigns are a job interview.

The press conducts that interview on behalf of the voters. Sometimes as questioner. Sometimes by offering a window through which voters view the applicant. The glass in that window must be clear, as [author George] Orwell said, and we must pick the right frame through which people view the contest.

But our window is caked over and frame is askew due to three simultaneous shifts: changes in the presidency, changes in presidential campaigns and changes in the press.

The change in the presidency is that it has grown more complex. More duties. More scrutiny. And the other branch isn’t lending a hand. Less reliable Congress.

The change in campaigns is that they are worse at testing whether applicants are ready for that complexity. For two reasons: Political parties once tested candidates for governing skills but they’re weak and don’t provide that test anymore. Toxic partisanship has shrunk the hiring criteria for the majority of voters. Instead of [asking] “Is the person good for the job?” there is one criteria: Is the candidate in the right party to fight the enemy in the other party?”

The shift in media, spurred by pressure for attention, has led to a narrowing of the frame through which the campaign is presented to the public, compressing the complex into TikTok videos or content suitable for audiences addicted to them.

In this environment, it’s hard to slow the horses and talk about job qualifications.

The TV gambit

To flesh out these ideas and build a vocabulary for our talk, I’d like to go back to the past to illuminate the present.

A November 1959 TV Guide essay was entitled “A Force That Has Changed the Political Scene.” The author argues that nothing in modern politics “compares with the revolutionary impact of television.” It creates a new connection between the audience and the candidate: “Honesty, vigor, compassion, intelligence — the presence or lack of these and other qualities make up what is called the candidate’s ‘image.”

That image, he argues, reveals elemental truths about the presidential candidate to the viewer, leaving voters with impressions the author declared would be “uncannily correct.”

In that world, he argued, party leaders would not dare run rough-shod over the voters’ wishes by picking a candidate in the traditional smoke-filled room that would contradict millions of voters who had drawn a personal conclusion based on what they’d experienced.

If you haven’t guessed by now, the author of the piece was Sen. John F. Kennedy.

Two months after this essay, he announced his candidacy for the presidency.

The article he wrote was an effort by the upstart senator to make the wish the father of the thought — or rather, the punditry the father of the candidacy.

Kennedy elevated television to get around the party bosses who were going to pick someone else. To do this, he had to build a permission structure within the party to make it okay to support him. Television was his permission structure. By elevating the democratic value of the medium in which he excelled, he hoped to boost the value of his campaign, which people would learn about through that medium. If voters liked the fresh-faced Massachusetts fellow on TV, it meant they’d come to an “uncannily correct” view about his fitness for the presidency.

It would be as if I told you that only speeches made in green blazers bring knowledge you can believe in.

That gambit was connected with a structural strategy: Kennedy used party primaries to show his support in the land. Primaries weren’t the automatic route to the presidency they are today.

In 1952, Tennessee Sen. Estes Kefauver tried to sneak past the Democratic Party establishment by running in state primaries. He won 12 of 15 elections, but since delegates were chosen by bosses at state party conventions, the presidential nomination went to former Illinois Gov. Adlai Stevenson, who hadn’t competed in a single primary.

The 1960 campaign that Teddy White became famous for covering super-charged two forces that have re-shaped the presidential landscape. It hastened the change of what was evaluated in candidates — increasingly the image was the thing — and because of Kennedy’s success in the primaries, it quickened the change of who did the evaluating — voters over party bosses.

What a story of change for the press to cover! But those two forces would also pull presidential campaigns out of balance.

The argument is not that image is newly powerful in presidential campaigns. It’s that the countervailing standards that constrained hero-worship of image started to diminish.

Few standards

Imagine that a candidate to be CEO of a large operation came to the board of directors and said what Kennedy was saying: I know you think you need one kind of CEO, but your customers like me using the product on Instagram.

The board would not be crazy to think customers, who might have had useful vibes about the product once it gets to market, nevertheless would have no basis to evaluate what kind of person would be required to run the company to get those products to market.

Whatever the board decided about this cheeky leadership candidate, they’d need a fixed standard against which to measure the new person’s qualities.

And to return from the boardroom analogy to the presidency: the Kennedy TV gambit demonstrates how candidates and parties build hiring standards for the American presidency on the fly.

This worried former president Truman, who called the primaries “eyewash” — superficial, without substance and not a good testing method for a serious job.

On the eve of the Democratic Convention in 1960, the 33rd president made a public statement calling out the young Kennedy: “Senator, are you certain that you are quite ready for the country, or the country is ready for you in the role of president in January 1961? I have no doubt about the political heights to which you are destined to rise. But I’m deeply concerned and troubled about the situation we are up against in the world now and in the immediate future. That is why I hope that someone with the greatest possible maturity and experience would be available at this time. May I urge you to be patient.”

Truman knew how challenging it could be to be unprepared. When FDR died, Truman, his vice president, didn’t know there was an atomic bomb project, among other things. His experience so influenced him, Truman is the one who insisted that the CIA give national security briefings to both major party candidates before the election. He knew that the experience and information gap between candidate and president could be deadly.

Truman was trying to assert a presidential standard because there isn’t one.

You have to be 35, U.S. citizen, born in America. That’s it.

There is more rigor in an application for the makeup counter at Macy’s than there is in the formal presidential evaluation process. In a civilian job, applicants are asked when they solved a difficult conflict between co-workers, how they motivate others, how they communicate their ideas.

What’s the presidential job application look like?

What qualities, skills and attributes should the president have? Is it the person you’d like to have a beer with? Are governors good? How about a businessman? Once you’ve decided what qualities a president should have, how do you test if the candidate has them? And who does the testing? By what authority?

Hiring standards: modern and founders

There were presidential standards when the job was created.

At this point, you might expect me to exfoliate you with quotes from the Constitutional Convention of 1787 or the Federalist Papers, and you will get that treatment. But let me start with the present.

If you were designing a system for evaluating the qualities for the leader in a complex organization, how would you design the process? The answer comes from a vast billion-dollar industry devoted to helping corporations, nonprofits, the military pick talent by identifying the fit between job applicants and job they’re being hired for in order to maximize talent to the task.

What method do organizations use to fill top positions? First, they check candidate attributes — character, decisiveness, adaptability. The building blocks to succeed in an unpredictable environment. If the company wants an outsider, maybe from an entirely different industry, they still look to make sure the candidate’s values align with the company’s mission and goals.

Second, organizations seek to verify if a candidate’s stated skills have been proven in real-world scenarios. They talk to references who have seen the candidate in action, in roles similar to the one they’re applying for. That is, roughly speaking, how you’d design leadership for success in a modern large enterprise.

It’s pretty much exactly as the founders designed the presidency.

The executive office designed that hot summer in 1787 at the Constitutional Convention was built around the personal attributes of what they would call the president– the habits of mind, behavior, character, virtue. Most of all, virtue. The internal stuffing would allow a president to act wisely in unpredictable circumstances. But also, those traits would guard against despotism, which they believed naturally tempted anyone with enough ambition to lead and who would be given the kind of power they were giving a president.

The founders’ system didn’t just take it on faith, though, that a president would have these qualities. They built a system designed to use sources familiar with what a candidate’s attributes looked like in practice.

These references were called presidential electors.

Presidential electors, as Hamilton put it in Federalist [No.] 68, would be “most likely to have the information and discernment” to make a good choice and to avoid the election of anyone “not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications.”

He went on to say, “It will not be too strong to say, that there will be a constant probability of seeing the station filled by characters pre-eminent for ability and virtue.”

I backed into the intentions of the founders because while, on the one hand, they’re relevant because we operate today in the system they designed, as a matter of argumentation, there are a lot of claims made where the warrant for the claim is merely a quote from the founders. I don’t think that’s enough. Plus, the founders were flawed in the light of their own times and flawed certainly by the analysis of today. But the selection process the founders designed has contemporary analogues today.

So, if our job in the press is to conduct a job interview, we have strong guidance: Evaluate candidate attributes. Seek demonstrated experience in relevant positions and first-hand candidate references, always keeping in mind the requirements of the job.

A contemporary and historical standard for the press to use, but it is in tension with the candidates and parties who would like to use another standard — the standard of public popularity, which they can sway.

And here, the founders really do have something to tell us about human nature because they were obsessed with it.

Campaigns are a contest to win power and the founders worried that to win power, candidates and parties would throw standards out the window. Then you’d have a lout in office without the internal attributes to check the temptation to misuse power.

Campaigns are about gaining power. Governing is about using it. The founders said it would be catastrophic if we fooled ourselves into thinking about a person who had the skills for attaining power would necessarily have the separate set of skills necessary to wield it wisely.

The sprawling presidency: assassinations and jokes

Standards are necessary because it’s a hard job.

Kennedy learned right away that Truman was right. “I wish I had spent more time learning how to be president instead of learning how to become president,” said Kennedy.

Kennedy came to office in the middle of its ongoing, increasing sprawl already far bigger than the founders had conceived. At the start of FDR’s term, there were half a million federal employees. There are now 2 million, with 1,400 of them subject to presidential appointment.

During FDR’s tenure, his entire cabinet could stand for a group photo and fit behind his desk. There were 11 of them.

(Social Security Administration)

In the Biden Administration, there was not enough room in the Oval Office.

(The White House)

The Biden team was too big for the Oval Office. They had to go outside to capture all 26 of them. There’s still only one president!

But let me try to give you a human idea of what the job is like to be president. The contrasting duties. The high-stakes activities that take place outside the camera’s view. The absurdity.

There is perhaps no better contemporary example of the acute loneliness of presidential decisions than Barack Obama’s decision to kill Osama Bin Laden. High stakes for the men he ordered to do it. A geopolitical gamble because he was stomping on Pakistan’s sovereignty and if it failed, would have been a huge blow to U.S. prestige as America wrestled with ISIS.

During final run-up to making the decision — because it was such a big call — the president chaired national security meetings about the raid.

If I were managing an assassination of any kind, I’d clear my calendar. But a president can’t do that. Here are the other things President Obama had to tend to during that period:

He gave an education policy speech, met with leaders from Denmark, Brazil, and Panama; held meetings to avert a government shutdown; held fundraising dinners; gave a budget speech; attended a prayer breakfast; held immigration reform meetings; made the final determination on a new national security team and announced it; planned for his reelection campaign; and launched a military intervention in Libya.

The day before Obama chaired his last National Security Council meeting on the Bin Laden raid, his White House released his long-form birth certificate to answer persistent questions about his birthplace raised by the man who would be his successor. Obama then went to the White House correspondents’ dinner, knowing that he had launched the make-or-break operation and that it was already underway. With that on his mind, he told jokes as the traditions of his job required.

Some of his jokes that night were about Congress highlighting a reality that while the presidency has become more complex, the other branch of government is not shouldering the governing load.

In arguing about the complexity of the office, I am not arguing to cut presidents a break because they’re busy. No more than you’d cut a brain surgeon a break because it’s … well … brain surgery.

I’m arguing that if we know what the actual job is, we can accurately understand success and failure in that job to hold incumbents to account and test those who want the job.

If we don’t understand the job as it really exists, then we end up measuring the occupants by the wrong standard. It’s like measuring a brain surgeon by his ability to spell.

Modern coverage of presidency

While the presidency was getting harder, the primary medium for evaluating it — television — flattened the office.

Television did not give people an uncannily correct view of the office holder, as Kennedy had predicted. But it did turn presidential leadership into something you had to be able to see or it didn’t happen.

It wasn’t all television’s fault, though. When the president became the principle initiator of public policy in the 1930s — because the Great Depression and then World War II made the presidency the office to which Americans turned for help — it was natural for analysts and pundits to focus on the one actor’s public role. We see it in the contemporary misimpressions of Eisenhower’s presidency, the consistent misunderstanding that the public Eisenhower was the same as the private one. That was exacerbated by early television. But the misjudging was also part of the way presidents were now understood: Public face was all.

It became necessary to show the president doing even if there was nothing to do. So, to give one example in April 1970, a fire imperiled the Apollo 13 trip to the moon. There was nothing President Nixon could do in the middle of the night, but his national security sdvisor, Henry Kissinger, says he woke him anyway. “We couldn’t tell the public that we had not alerted the president,” said Kissinger. “It is important the public has a sense that the president is on top of the situation.”

This performative expectation overloaded the presidency. We expected to see the president acting and see results even when a) performance wasn’t the solution and even might hurt progress and b) performance created the expectation that results might come quickly, which, on complex issues, they don’t.

Even the most TV-focused president of our lifetime was frustrated about the requirement for performance. “Oh, he’s just watching TV,” said Trump adviser Kellyanne Conway, referring to a regular critique if Trump wasn’t seen addressing a particular issue. “No, he’s doing things you can’t see because his first duty is to protect the American people.”

A contemporary example of this: An article recently questioned whether Biden’s theory of the presidency was being tested by a pile-up of events from the Middle East to Ukraine to China.

Evidence he was overmatched?

“For the second straight day,” reads the article “Biden also stayed entirely out of the public eye … Biden’s sole address to the nation in the wake of the attacks came hours after it, though it was announced that he would make public remarks on the crisis Tuesday. Since Saturday, he had stayed behind closed doors as cable news and social media were filled with gruesome images of the Hamas attacks.”

Proof that his presidency had tipped was based entirely on performance.

There are a whole host of things the president could and was doing out of sight that were more valuable but weren’t listed. Consulting allies, consulting enemies, talking to national security advisers about secret information, managing the hostage families, etc.

Every day, the White House declares a lid for the press to let them know the president will have no more public events for them to cover. When the Biden White House declared a lid early on a particular day, a number of his Republican opponents howled as if a president not seen was knocking off for the day.

“Alabamians don’t work those kind of hours,” said Sen. Tommy Tuberville.

The political benefit of this critique is that it allows you to knock a president based on feeder review, which everybody congrats very easily and allows you to jump over any of the complexities of the issue.

When performance gains such primacy, it allows charismatic chaos entrepreneurs to have an effect over the system that their lack of experience would not otherwise grant them.

Congressman Matt Gaetz, who had sufficient power to depose a speaker, characterized the modern expectation this way: “If you’re not making news, you’re not governing.” This performative and ego-centered vision of governing is so backward that the founders would spin in their graves with such ferocity it would create the turbine energy sufficient to power a mid-sized Midwestern city.

My point is not that a president not seen is doing secret great work. It might be possible that the unseen work is calamitous or work not taking place behind the scenes is a dereliction.

We’re looking for balance:

- Reduce the weight we put on the work we can see unless it genuinely warrants it.

- Explain — even when you don’t have access to it, the work a president does that goes unseen.

- Recognize and cover lots of non-flashy governing work an administration does.

Striving to give people a view of the presidency that is outside of their view is the best way to help them stay informed about what the job requires.

Presidential coverage suffers from the “streetlight effect.” You know the old joke about the streetlight. A policeman comes upon a drunk on his hands and knees under a streetlight. “What are you doing?” he asks. “Looking for my keys,” says the drunk. “Did you drop them here?” “No, I dropped them in the park, but the light is better.”

Overemphasis on presidential communication

In 2010, a Slate magazine article about President Obama’s failure to sell health care was headlined “Death of a Salesman.” Obama, the golden-tongued orator of the 2008 campaign who sold himself to the electorate, had lost his key skill. He couldn’t sell health care.

Political scientist Brendan Nyhan took issue with the grand conclusions of the piece’s confident author.

“Presidents can rarely generate significant shifts in public opinion in support of their domestic policy agenda. Obama’s failure to generate increased support for the stimulus and health care is not the least bit surprising, especially given the political environment in which he’s operating,” [Nyhan wrote]. [The article’s author, John] Dickerson is constructing a post hoc narrative about Obama’s poll numbers using the epistemology of journalism, which treats tactics as the dominant causal force in politics. Within that worldview, if Obama’s numbers used to be high and they are now low, the only logical conclusion is that “his ability to persuade and change minds is seriously damaged.”

Who was this Dickerson fellow?

Oh dear! I was the author of that Slate piece. And I was wrong. I had sallied forth with my confident analysis into the latest in a long line of analysts who thought presidential oratory was all and that when done well, it could change public minds. There’s no evidence for this.

I wasn’t alone during the Obama years. One of the most passed-around New York Times’s opinion pieces in the early Obama years was entitled “What Happened to Obama?” It argued he was in political trouble because he’d failed to tell a compelling narrative to win over people.

And the author of that article took it in the neck from political scientists, too.

“It’s hard to exaggerate just how wrong Westen’s argument is, starting with his assumption that policies flow ‘naturally’ from this ‘simple narrative,’” wrote Middlebury political scientist Matthew Dickinson. The argument “falls prey to a basic misconception: that a President can control the narrative by which the public defines his presidency.”

But the myth of this power [of] speechmaking will not die. Here’s a recent story, entitled “Biden’s Broken Bully Pulpit.”

“Biden, who was never a charismatic speaker in his political prime, is badly struggling to persuade the public of anything.”

The article argued that Biden was failing to convince people that the economy was getting better, as if effective speaking could somehow overcome people’s feelings about inflation, partisanship and the effects of partisan media.

The article cited FDR and his fireside chats as evidence that eloquent presidents can shape public opinion. That’s not correct. Two of FDR’s biggest failures were the subject of fireside chats and protracted sales campaigns — his effort to pack the court and purge Senate Democrats in primaries. Both failed.

What about Reagan, you might ask?

After Reagan won a landslide in 1984, Reagan tried to sell the country again on aid to the Contras. In April 1985, his pollster, Dick Wirthlin, explained where oratory worked and where it didn’t.

It worked “when the issue considered already has strong grassroots support.” And it worked when he “amplified the public’s political voice,” galvanizing popular sentiment that already existed.

Reagan failed when he tried to convince the public of something it did not believe, said pollster Wirthlin. “By raising the political stakes and the public saliency of this particular issue,” wrote Wirthlin, “you would not only put into jeopardy the favorable job approval you now enjoy, but, more importantly, you will generate more public and congressional opposition than support.”

Wirthlin was articulating what the great presidents knew about the limits of the office. “With public sentiment,” Lincoln said, “nothing can fail; without it, nothing can succeed.” FDR: “I cannot go any faster than the people will let me.”

The mismatch between our expectations of presidential rhetoric and the reality of its effectiveness is just one way our expectations for the office are misaligned. If we get the history wrong and have our expectations out of whack, we apply the wrong metric to presidencies, we deliver the wrong assessment that becomes the basis of voter decisions about accountability and support. And we fail to look at other institutions like Congress or local government for solutions because we’re expecting the presidency to do things it cannot.

Political scientist Nyhan — the one who helped bring me into the light — calls the expectation gap Green Lanternism, based on the DC comic book character whose power is determined by his willpower. The harder he wants something, the better chance he’ll achieve it.

In the presidential context, it is “the belief that the president can achieve any political or policy objective if only he tries hard enough or uses the right tactics.”

We see this particularly on the border. Both Trump and Biden suffer from the myth that they can do more at the border than they actually can.

A recent political science paper that Nyhan and his colleagues published sought to quantify the gap between the superhero expectations of the presidency and the reality of the job.

The frame for the investigation is the one that I’ve tried to pick from my talk tonight. The idea that unless people have the right frame for understanding the presidency, they won’t be able to hold presents to account for the right things and they won’t have the right frame for evaluating people who want the job.

Political scientists surveyed expert opinion on perceptions of presidential control. They asked experts to rate on a scale of 1-5 the level of control presidents have over various issues. The issues ranged from choosing a running mate to influencing forces like inflation rates and gas prices.

Regarding selecting a running mate, experts believed presidents had near maximum influence, rating it 4.3 out of 5, on average.

When it came to presidential control over inflation rates and gas prices, experts correctly asserted presidents have little control, rating those factors 1.69 and 1.92 out of 5, respectively.

Yet a CBS public opinion poll revealed a wildly different perception. Sixty percent of the public believes the president has control over inflation. Those respondents also said inflation was their most important issue. On their most important voting issue, their views are misaligned with the reality of the presidency.

That misimpression is created when you cover the presidency as a performance job where any problem can be solved through presidential willpower.

The way we campaign now

Now to presidential campaigns, Do we cover the office as it is or the office of mismatched expectations?

There are very few Teddy White style books in the early days of the republic because there were no campaigns to cover.

The founders thought any candidate who personally angled for the presidency was not fit for the job. Such outward ambition would lead to despotism once it was given presidential power. Standards of character, the stewardship obligations of the office, prevailed.

Standards of behavior were still quite robust 70 years ago. Two aspects that define the modern campaign were shocking novelties then. In 1948, the Washington Post wrote an editorial chastising president Harry Truman for speaking “off the cuff,” as it was called at that time. Wrote the Post: “When the President speaks, something more than an off the cuff opinion or remark is expected.” The paper reminded him that the whole world was watching.

On Sept. 29, 1956, the Cedar Rapids Gazette front page read: “Ike setting up policy of firing back.” In Delphos, Ohio, the front page read: “Fire Back When Rivals Go Too Far — Ike’s New Policy.” The Daily Herald in Tyrone, Pennsylvania heralded: “Ike decides to answer Demo ‘lies.'” This was a novelty — a presidential incumbent responding to a challenger, because Eisenhower had previously resisted participating in what he called the “noise and extravagance” of the campaign.

By the way, the “firing back” amounted to correcting challenger Adelie Stevenson’s figures about inflation.

The point: Standards of reason, logic, probity, decorum, a sense of the weight, even of campaign speech, governed the campaign.

But as performance became the thing in campaigns and the audience determined what worked, rather than elected politicians in the parties, standards became more malleable. Authenticity is now the thing. Using a teleprompter to deliver thought-out remarks is a sign you’re a phony.

Party insiders who once paid attention to standards were replaced in the nominating process by the direct will of the people, which has many salutary benefits. Representation of minorities, weakening bossism. But the role Hamilton talked about, that Truman tried to play with Kennedy, disappeared. Superdelegates — insiders, elected officials, those in the political swim — whose votes were once given extra weight in party nominating conventions are gone now.

As the candidate became the tribune of party voters, they had to stay in sync with what excited activist voters. When the base wasn’t excited, the candidate had to goose them to a roar. The presidency was designed to require cool reason, but selection for it now required hot-headed antics to get raise money, capture social media and win over key activists.

“I’d get out there and I would talk about policy and there was no adrenaline rush and people kind of went ‘uh-huh, uh-huh,’ said Howard Dean of being a candidate. “And I really wanted that huge charge of being able to crank them all up and get enthusiastic and I would succumb to that.”

If we reverse-engineered the presidency from the campaign as we cover it, the American president would spend hours a day raising money, listening to the bad ideas of billionaires, speaking only to people who agree with him, and addressing not national questions, but the ones that get his jumpy friends most jumpy.

Complex problems, when they appeared, according to the logic of the campaign, would be solved with an entertaining Tweet or a snappy debate comeback.

The president as chief partisan warrior has led to what UVA’s [the University of Virginia’s] Sid Milkas calls “executive centered partisanship.” Candidates mobilize ideological supporters in campaigns. They don’t compete to solve common problems and when those candidates get into office, the requirement to mobilize on ideological grounds continues.

The most recent example of how a president as a partisan warrior drives the partisan agenda came when Donald Trump pushed Republican senators to kill immigration reform with Joe Biden so that it would help Trump in the election. It wasn’t a policy disagreement. It was purely political.

Now Sen. Chuck Grassley says he’s skeptical about bi-partisan tax reform, which would help kids in poverty, because he says it would give Biden a win in an election year.

Imbalance in campaign coverage

How are we doing covering this campaign landscape? From here on out where I talk about us, I do not absent myself from the critique — things I have done, or failed to do or could do better.

First, there’s too much coverage of what has long been called the horse race. Who is up and who is down? What tactics are being used? Thomas Patterson’s, from this very institution, study of the 2016 race found only 10% of television political coverage was about issues. The rest horse race.

This is the most familiar critique and I’d like defend it. It would be crazy not to cover how presidents win power. Understanding the tactics explains why they won. Furthermore, understanding how campaigns work explains why money influences governing and how voters pressure presidents.

Also, it’s not the press that forces the horse race on the audience. People love the horse race. I’ve been on the road covering politics for 30 years more or less. What do you get asked? Horse race questions.

What should we cover? I’ll get to specifics in a minute, but the horse race illustrates, in the easiest way, the all-encompassing problem: The press is too wedded to covering the structure of how parties select presidents. We need to stay put and cover the presidency itself, by the standards of the office.

In the same way people talk about outsourcing to social media the curation of our information diets and handing ourselves over to the algorithms unaligned with our interests, the press has done this with campaigns. When we cover just the campaign as it takes place before us, we are handing over our framing responsibility to people who do not have the public’s interest at heart. They have the candidate’s interest at heart. The party’s interest at heart. They have power at heart.

Second, we all took Kennedy’s argument too far. We thought we could form uncannily correct conclusions. When we were let down, we didn’t drop the patent scoring. We asked for ever-greater displays of it. Now authenticity becomes the most important attribute in a campaign, though it is not the most important attribute in governing.

This excessive emphasis on authenticity was captured in the New Yorker cartoon by Paul Noth.

The candidate, a wolf, is running on eating sheep. “I will eat you,” reads his billboard. One of the sheep grazing beneath it says: “He tells it like it is.”

Third problem, we are obsessed with polls. The issue of the economy is a good example of how this puts us off course. Instead of explaining the economy so that people might have a better understanding of a president’s control over inflation or not, we just poll people about how they feel about inflation.

They say they’re concerned about inflation and we ask candidates what their plan is for inflation without stopping to think if a president has much control over inflation or whether there are 20 other economic issues we should be asking about where a president does have a hand.

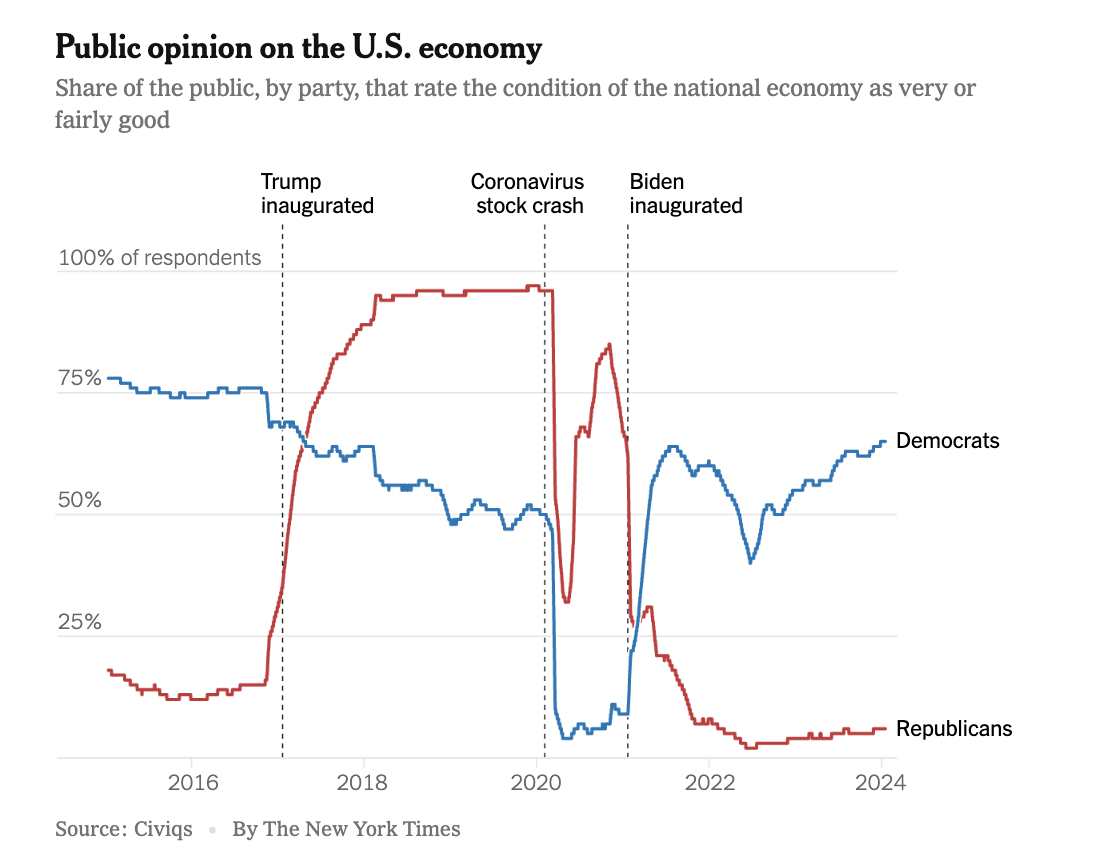

More broadly, polling about issues has become less useful in our partisan age. Here is a graph charting views about the economy by party.

A vast number of Republicans started thinking the economy was awful the minute Biden was elected. Given that feelings about the economy are now a proxy for presidential preference, we shouldn’t treat them as Solomonic views of real life.

The problem with polling like this is people in the press are apt to draw conclusions about policy from these polls. If the public doesn’t like what Biden is doing, that his policies must be bad. But that isn’t so. Biden may have awful policies, but many of them don’t like what Biden is doing because he’s on the wrong team.

The fourth point about the way we cover campaigns: In presidential campaigns, we don’t keep in mind the office of the presidency as it actually operates.

This has a few elements to it:

First, we spend good deal a less time on foreign policy in campaigns than the presidency does.

“The biggest shock presidents face is that eighty-five to ninety percent of the job is all about foreign policy, which is about five percent of the campaign,” says Elaine Kamarck, author of Why Presidents Fail, formerly of the Kennedy School. “All of the sudden you’re having to make decisions and learn about countries and meet with world leaders and then on top of that there’s the secret world of intelligence.”

No greater example of the mismatch than the 2000 presidential race. During the Bush v. Gore presidential debates, the word “terrorism” never came up. It defined the next two presidential terms and beyond.

Second, we don’t test for surprises.

I asked Condi Rice what question I should ask candidates. She said, “Ask them what would surprise them and how would they handle it.” The point was to see if they understood that surprises are central to the job — terrorist attacks, pandemics.

In 1913, after Woodrow Wilson became president, he remarked, “It would be an irony of fate, if my administration had to deal chiefly with foreign affairs, for all of my preparation has been in domestic matters.” Fate responded. Wilson soon faced World War I.

Here’s something a presidential primary candidate said in a GOP primary debate I moderated in 2016. “The next president is going to be confronted with an unforeseen challenge. That’s almost certain. It could be a pandemic, a major natural disaster or an attack on our country. The question for South Carolinians and Americans is who do you want to have sitting behind the big desk in the Oval Office?”

It’s a truth that the son and brother of presidents would know. But since it was Jeb Bush and Trump had declared him low energy, no one paid attention.

He was prescient about the pandemic, which has led some QAnon chaos entrepreneurs to claim Jeb knew something about COVID-19, which is, of course, preposterous since that was Taylor Swift’s operation.

The presidency is an organization not a single-person office. When I wrote a book on the presidency, I asked presidents and presidential aides in every administration going back to the Johnson administration what one quality they’d want to know about a president and they all said, “Who is going to be on their team.” Who will surround them?

When was the last time the press asked a candidate about his or her team-building skills?

But this is what they say about team building in other large organization:

“I’d rather interview 50 people and not hire anyone than hire the wrong person,” says Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon. “The secret of my success is that we’ve gone to exceptional lengths to hire the best people in the world,” said Apple’s Steve Jobs.

Mike Bloomberg talked about the press’s misunderstanding about this in the mayoral context:

“The press wants to write the ‘100-day story,'” [Bloomberg says]. “They asked: ‘What’d you do in the first 100 days?’ And I said, ‘I built my team.’ And they responded, ‘Yes, but what legislation did you pass? What did you accomplish?’ And I said, ‘I built my team.’ They never got the concept.”

So what should we do?

Now to what the press should do. Our final section. We’re almost home. These are the things I tell myself. I’d paste them on the mirror, but there would be no room for mirror left.

Cover what the job requires — team building, experience making decisions — and what is realistic. But also highlight governing qualities like restraint, character, temperament.

Those are fuzzy qualities, so explain in practical terms what those words mean in the job.

Character, for example, is so crucial to the job a presidential campaign book is called Character Above All, which captures the basic idea that it’s a lonely job and a president needs an internal compass to make tough decisions.

If we let the campaign define character, it could mean anything. In 1992, it meant Bill Clinton’s private behavior. Republicans have dropped that idea. Now some of them define character as saying offensive things and being proud of it.

In 2008, Mike Huckabee said a rival’s lack of honesty was disqualifying: “If he lies in the campaign, he’ll lie as president.” In 2024, Huckabee campaigned for Trump, whose number of campaign and governing lies set records.

The political scientist James Wilson’s definition of character is the useful one: “empathy and self-control.”

We need to explain what these characteristics mean in practice.

Empathy means taking into account the rights, needs and feelings of all, which a president of a nation must do. So we should ask questions that explore that.

Self-control is vital because the presidency is a constant test of fealty to duty over personal desire. It is a job of action, but frequently not acting — restraint — is the key action because you must keep long-term consequences in mind. We should explore how candidates have shown restraint and think about it.

Second, don’t let the parties pick the issues. Candidates and parties want to talk about wedge issues that spark their voters and make the other candidate look bad. This grabs attention, fuels social media, raises money.

It often does the country no good. It lets candidates duck tough issues and avoids educating the public about the most important issues.

We should cover the stories that affect large numbers of people and over which the federal government has considerable influence: health care, immigration, income inequality, the death of the middle class, foreign policy, the environment and energy.

These matter to more Americans and candidates need to have answers for those issues, especially if they don’t want to talk about them.

Stay close to the electorate. Listen for their issues. Not every opinion is useful. Twitter proved that. But policy is connected to candidates through humans and humans remind reporters to be humble and keep us centered on why we’re doing this.

Covering an issue means more than listing candidate positions. It means illuminating the tradeoffs they’ll face:

- deficit reduction versus investment.

- spending versus taxes.

- immigration versus labor markets.

Presidential campaigns are a national moment to examine important issues, whether candidates have anything to contribute or not. So if the polling shows people are wrong about the unemployment rate, inflation, growth, we should aim our energy at explanation just as we would if they were wrong about a public health measure.

Don’t spend too much time asking voters who they think will handle the economy better. Ground stories in specific challenges candidates and the country will face:

- Will a candidate extend the 2017 Trump tax cuts?

- How will they invest in a future affected by AI?

- Does the COVID-19 generational learning loss matter to American productivity?

- How will tight immigration laws affect inflation?

- Medicare and Social Security are going bankrupt? What are the options?

The Wall Street Journal did this nicely with a piece recently headlined “$6 Trillion in Taxes Are at Stake in This Year’s Elections.” WSJ explaining that the ultimate resolution will affect family budgets, corporate profits and the federal government’s fiscal health amid rising debt.

This also means covering the issues that will surprise the next president. If a Time article in 2000 could say “our next President may preside over the first catastrophic terrorist attack,” debate moderators could have been forward thinking enough to ask about that issue in debates. Candidates will dodge, yes, but a) we shouldn’t settle for that, and b) even if they do, keeping the surprise question front and center reminds all voters it’s something we should keep in mind when making our selection.

Third, make context king.

Now to Teddy White. I am an acolyte. Just out of college, I bought all of his books used at the Strand bookstore. I read them as a campaign reporter. I read them again for my campaign podcast and book Whistlestop. I have the 1972 [book The] Making of the President that Time’s Hugh Sidey, a great chronicler of the presidency, loaned me that has an inscription from White, which is like having a Babe Ruth bat signed over to Hank Aaron.

White gets grief for launching scooplet journalism, but I loved him for the exact opposite reason. He helped teach me about going up to 30,000 feet. Seeing the larger context in small acts.

That’s the instinct we should cultivate on every presidential story. What’s the larger context? So when Donald Trump and Joe Biden each visit striking UAW [United Auto Workers] workers, don’t talk about Michigan voters or blue collar workers. Talk about the fraying of the social contract between companies and their workers, the status of the American Dream, what one generation owes another, what government can effectively do to create opportunity.

This particularly relates to covering the threats to Democracy. That is the ultimate context exercise. You can’t do any of what I’m talking about tonight if the system for elections is corroded.

Fourth, cover events outside the campaign with a presidential mindset.

The press can keep voters attuned to a president’s obligations by adding a note about presidential context to reports otherwise focused on other topics. For example, Sweden joining NATO is about fallout from Russia’s invasion, Turkey, Hungary, etc., but the story also speaks to U.S. commitments abroad and whether presidents will uphold them.

Similarly, record Affordable Care Act enrollment raises questions around candidates caring for the vital program.

Discussions at Davos about hypothetical pandemics get at the surprises presidents face and the long-term thinking the job demands. Almost every major story has a presidential angle about duties, character and mindset.

Putting 2024 in context

I will conclude with this specific presidential campaign. I can’t talk about keeping a campaign in context of the presidency without addressing the special context of the 2024 campaign.

Earlier, I said we’re a long way off giving voters the material to judge candidates on a logical standard.

The two components of that evaluation standard are an understanding of a candidate’s attributes, behaviors, habits of mind and, second, an evaluation from credible references about how a candidate would do when faced with presidential-level challenges.

In general, that’s missing from campaigns. But in 2024, we have the most information we’ve ever had on those two tests for Donald Trump.

The information about Donald Trump has come in books, of course. But what elevates the quality of material is that much of the information has come under oath, under penalty of perjury, by people who would not talk to authors. From the Jan. 6 committee testimony and soon trials, we have testimony about Donald Trump’s personal attributes and actions as president in the months after he lost the election in his attempt to overturn the election.

We also have testimony from the leaders of his party. The top Republican in the Senate, the top Republican in the House, the last Republican vice president and admirers like Sen. Lindsey Graham. These are officials in the elector model Hamilton talked about. All said, Donald Trump was responsible for the attack on the capitol and for doing nothing once it happened.

Direct, verifiable views about an effort to undermine the constitution by a president sworn to protect it.

We also have first-hand testimony from those who worked closest to the GOP front-runner with standing to make judgments about how he behaves when faced with presidential tasks. Secretaries of defense, attorney general, chief lawyer, chiefs of staff. The New York Times counted 18 of such rank. They all say he is unfit for the office. If you were hiring a CEO, what would you think of a candidate who had 18 high-level negative references.

I have tried to build a case here that the press has an obligation and opportunity to keep coverage focused on a logical and historical standard of the presidency. On the basis of that standard, Donald Trump gets disqualifying marks. The only way to escape that conclusion is to wave away standards, or create new ones. But to create new standards would be for the purpose of electing a person to another job, not the presidency of the United States.

We have drifted in our coverage of the presidency — by circumstance, the financial squeeze on journalism, spectacle, pressure from public outrage over genuine disappointment with office-holders and reporters alike. Evaluations of who is fit to occupy the office must return to what I was struck by 20 years ago in George W. Bush’s driveway: a focus on what the president’s actual duties in office are. That is the job those of us in the press must now return to doing.

Qualified applicants welcomed.

Expert Commentary