As employers, colleges and school systems across the U.S. mandate COVID-19 vaccinations, a variety of organizations are clamoring to help people use religious exemptions to avoid getting shots.

Anti-vaccine advocates, local churches and legal groups have offered their assistance for free or for a fee, even as high-ranking faith leaders worldwide speak out in support of COVID-19 vaccines. Pope Francis, for example, recently urged people to get inoculated as an “act of love.” The First Presidency, the highest governing body of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, also encourages COVID-19 vaccination.

Many of those who oppose immunization also are going online to share tips and resources and strategize ways to forgo required vaccinations on religious grounds. Workers, parents and others are gathering in Facebook groups that, as Mother Jones magazine reports, have grown from hundreds of members to thousands within a short period.

Kiera Butler, a senior editor at the publication, writes that while some “seem earnest in their religious objections to the vaccines, others skirt the line of opportunism.”

“Though most of the religious exemption social media groups are only a few weeks old, it’s clear that they have already become powerful sources of camaraderie and identity,” she writes.

A 2018 study published in the journal Sociological Perspectives shows how some parents already were gaming the system. In “I Have to Write a Statement of Moral Conviction. Can Anyone Help?”: Parents’ Strategies for Managing Compulsory Vaccination Laws,” sociologist Jennifer Reich describes how parents strategize to use vaccine exemptions and “craft claims of religiousness to justify opting out of vaccines, even as they lack religious beliefs that would be violated by using vaccines.”

Some parents allow their kids to receive one or more vaccines but tell schools the children haven’t had any so they qualify for a religious exemption, writes Reich, a professor at the University of Colorado Denver.

“Outside of formal documentation, parents suggest to each other that they manage information carefully,” she writes. “As one mother advises online, ‘Whatever you do, less is best, be nice, not defensive. Provide the minimum letter, reiterate the statute and be vague if necessary. Don’t discuss your choices with other school families unless you trust them.’”

As of Sept. 27, more than 213 million people nationwide had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine — 64% of the population, data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show. Vaccine hesitancy is strong in some parts of the country. Vaccination rates tend to track closely with political views — most under-vaccinated states lean Republican, Anthony Fauci, the White House’s top medical advisor, told The Boston Globe.

A Pew Research Center survey conducted in August supports Fauci’s assertion. It finds Democrats are much more likely than Republicans to report receiving at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine — 86% compared to 60%.

Meanwhile, several recent polls indicate a majority of vaccinated Americans want COVID-19 shots to be required. A poll conducted this past summer by the COVID States Project, a group of researchers from various universities, finds that 64% of U.S. adults think federal, state or local governments should require everyone to get immunized against COVID-19.

Because vaccination, civil liberties, employment law and health policy are all complicated topics, we asked law professor Dorit Reiss for advice on how journalists should think about and cover religious exemptions to vaccine mandates. Reiss teaches a course on vaccines at the University of California’s Hastings College of the Law. She also researches and has written extensively on vaccine mandates and religious exemptions.

Here are the four tips Reiss shared:

————————-

1. Don’t assume employers, colleges or schools that require COVID-19 vaccinations will offer religious exemptions. If they do, don’t assume exemption requests will be approved.

Title VII of the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 requires U.S. employers, including government agencies, to accommodate employees whose religious beliefs and practices conflict with work requirements — so long as it doesn’t create an “undue hardship” for the employer, Reiss explains. That means workplace administrators must let employees request an exemption if vaccines are required for work, but don’t have to grant them.

An accommodation “may cause undue hardship if it is costly, compromises workplace safety, decreases workplace efficiency, infringes on the rights of other employees, or requires other employees to do more than their share of potentially hazardous or burdensome work,” according to the U.S. Department of Labor. In 1977, the U.S. Supreme Court interpreted “undue hardship” to mean incurring more than a de minimis, or minimal, expense.

Title VII applies to employees at colleges and K-12 schools, but not students. State law generally governs whether college students and kids in kindergarten through high school can ask to be exempted from receiving the various vaccines required for enrollment. Because of that, policies vary considerably across the U.S.

As of mid-September, 26 of the nation’s 50 biggest public university campuses did not require students to get inoculated against COVID-19, an analysis from The Associated Press finds.

While no state has yet mandated COVID-19 shots for students in kindergarten through 12th grade, some school districts in California are considering a COVID-19 vaccine mandate for kids. Earlier this month, the Los Angeles Unified School District became the first major school system in the U.S. to require students over age 12 to be vaccinated, the Desert Sun in Palm Springs reports.

Six states prohibit K-12 schools from granting exemptions to vaccine requirements on religious grounds, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Those states are California, Connecticut, Maine, Mississippi, New York and West Virginia.

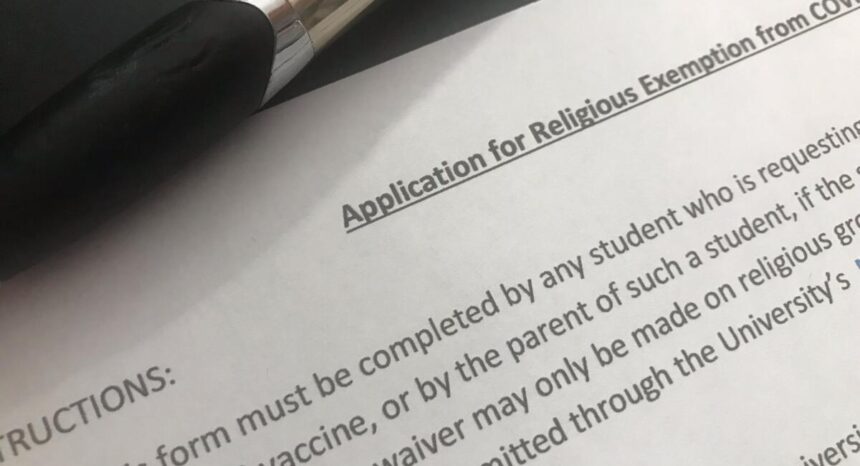

2. Know that some people make false claims to obtain religious exemptions.

Reiss argues there are two major drawbacks to offering religious exemptions to vaccine requirements. First, many people game these exemptions, falsely claiming a religion they don’t follow or that their religious beliefs prohibit inoculation when they actually do not, she says. Secondly, employers, government agencies, colleges and others have difficulty verifying the sincerity of claims — or don’t bother.

“Given the amount of misinformation about vaccine safety and the virus, chances are that most of the exemption requests are from people who do not want to get COVID-19 vaccines because of safety concerns or misinformation about the pandemic,” Reiss writes in a recent article on the Bill of Health blog, published by the Petrie-Flom Center at Harvard Law School.

A 2013 paper in the academic journal Vaccine offers a broad overview of how the teachings of various religions apply to vaccines.

Academic research indicates some people seek religious exemptions for reasons that are not actually rooted in religion. For example, a 2018 study in the Journal of Medical Ethics finds that employees sought religious exemptions to a Cincinnati hospital’s flu vaccine mandate for various reasons, including concerns about the benefit of the vaccine. Some employee claims focused on false or misleading information about how the vaccine was manufactured.

3. Understand the most common reasons people seek religious exemptions.

Reiss says religious exemption requests tend to focus on one or more of the following four issues:

- Vaccines are linked to abortion.

Cells derived from aborted fetuses have been used for years to make vaccines, including some COVID-19 vaccines. Public health officials stress that while researchers used cells originally isolated from human fetal tissue to develop or test some COVID-19 vaccines, none of the vaccines authorized for use in the U.S. contain fetal cells. They also stress the vaccines don’t use fetal cells from recent abortions.

“Cells that make up the ‘cell lines’ used for certain COVID-19 vaccine development came from two elective pregnancy terminations that occurred in the 1970s and 1980s,” the Michigan Department of Health & Human Services points out in an informational document.

When making vaccines, fetal cells can be used “as miniature ‘factories’ to generate vast quantities of adenoviruses, disabled so that they cannot replicate, that are used as vehicles to ferry genes from the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19,” explains Science magazine, published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. “When the adenoviruses are given as a vaccine, recipients’ cells begin to produce proteins from the coronavirus, hopefully triggering a protective immune response.”

Fetal cells were used to produce and manufacture the Johnson & Johnson vaccine and during testing of the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines, Reuters Fact Check confirms.

- Vaccine manufacturers use blood to create vaccines.

Vaccines typically do not contain human blood products. However, products derived from animals, including animal blood, can be used to grow disease-causing bacteria and viruses in a lab. Researchers also use blood from horseshoe crabs to test vaccines and injectable drugs to ensure they don’t contain harmful bacterial endotoxins.

While many Jehovah’s Witnesses avoid blood transfusions and certain medical treatments that involve blood products, they view vaccination as a personal decision.

- The Bible calls the human body “a temple of the Holy Spirit.”

The New Testament makes multiple references likening the human body to a temple. Some people argue getting injected with a foreign substance such as a vaccine would defile their bodies, which they say is sinful. - Various religious doctrines direct people to take care of their bodies.

Vaccines are designed to protect human health, but some people argue they are harmful, partly because of their side effects. For instance, some adolescents and young adults reported mild heart problems after receiving the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines.

Muslims, Jews and others whose faith traditions forbid the consumption of pork have raised concern that some vaccines are manufactured using ingredients derived from pigs, including gelatin, used as a stabilizer. However, scholars of Judaism and Islam have deemed such vaccines permissible, vaccinologist John Grabenstein writes in “What the World’s Religions Teach, Applied to Vaccines and Immune Globulins.” Grabenstein, the president of consulting service Vaccine Dynamics, notes that vaccines contain tiny quantities of these components and that dietary rules do not apply to vaccines because they are not ingested.

4. Stress that employers, colleges and schools can ask questions and require documentation to help them assess the sincerity of an exemption request.

Some organizations give employees or students a short form to sign to request a religious exemption, and approve all or nearly all requests, Reiss says. Other organizations, on the other hand, require much more information to help them decide whether to grant an exemption, including a written explanation of how the requestor’s religious beliefs conflict with vaccination requirements.

Administrators also are permitted by law to ask questions about the requester’s belief system and medical history. For example, if someone seeking an exemption opposes COVID-19 vaccines because fetal cell lines were used to develop or test them, an administrator might ask whether that person takes Tylenol or other over-the-counter medications developed or tested using fetal cell lines, Reiss points out.

Federal law protects employees’ religious beliefs, observances and practices, regardless of whether workplace administrators are familiar with them. Employees don’t have to belong to organized religions. Because religious beliefs can be unique to each person, they also don’t have to make sense to the people deciding whether or not to grant exemptions.

“You can’t say that their beliefs are irrational,” Reiss adds, stressing that requests should be judged based “just on their sincerity.”

The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission advises employers to “ordinarily assume that an employee’s request for religious accommodation is based on a sincerely held religious belief.”

Expert Commentary