“Unprecedented” is a word that journalists should use sparingly, but it’s appropriate for describing the controversy surrounding Biogen Inc.’s drug Aduhelm for Alzheimer’s disease.

In the wake of the June 7 approval of Aduhelm by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the consumer watchdog group Public Citizen called for the resignation of several senior agency officials. Two House committees began an investigation into the FDA’s handling of the Aduhelm application. And the FDA’s approval of the drug prompted the internal watchdog branch of the Department of Health and Human Services, its Office of Inspector General, to review how the agency is managing a process known as accelerated approval.

In 1992, the FDA launched the Accelerated Approval program to expedite the availability of new drugs that address an otherwise unmet medical need. This allows the FDA to approve drugs quickly by relying on a surrogate endpoint, which the agency describes as “a marker, such as a laboratory measurement, radiographic image, physical sign or other measure that is thought to predict clinical benefit, but is not itself a measure of clinical benefit.”

In clearing drugs for accelerated approval, the FDA takes a risk that promising early signals seen in drug studies, such as an ability to keep tumors from growing, will eventually pay off by resulting in a clinical benefit — improving or extending patients’ lives.

The FDA granted Aduhelm its accelerated approval based on a surrogate marker, its ability to reduce the build-up of sticky amyloid plaques in the brain, which the agency called “a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease.” At the heart of the concerns about Aduhelm is a question some doctors have asked in recent years: When granting accelerated approval of a drug, is the FDA doing enough to make sure there’s adequate evidence of the drug’s expected benefits?

The FDA doesn’t conduct large studies of medicines in patients. Instead, it relies on the results of studies that drug makers fund, which are usually led by scientists at academic institutions.

After winning an accelerated approval, companies are expected to continue their research and either deliver strong evidence of a meaningful benefit to their drugs, or agree to withdraw the FDA’s accelerated approvals. But drugmakers sometimes are slow to deliver these results or balk at allowing withdrawals of these FDA approvals even when further studies cast doubt on the benefits of the drugs.

Accelerated approval is an important topic for journalists to consider in their ongoing coverage of drug costs in America.

“Private insurance companies, Medicare, and Medicaid pay millions—maybe billions—of dollars for drugs for which we do not know the real benefits and risks. This raises insurance premiums and wastes tax dollars,” write Sarah DiMagno, Aaron Glickman and Dr. Ezekiel J Emanuel, in a 2019 invited commentary in JAMA Internal Medicine. “Exorbitant drug prices are bad enough for treatments that work. Charging vulnerable patients for drugs without evidence that they actually improve patients’ survival and quality of life is unconscionable.”

Emanuel returns to this topic in a September Viewpoint article in JAMA, noting the concerns raised by the Aduhelm approval. He urges changes to the FDA’s approach to handling accelerated approvals, including calling for automatic termination of approvals if confirmatory trials are not complete within a set timeframe.

“As of December 2020, a total of 24 of the drugs approved on the basis of accelerated approval had been on the market for more than 5 years without confirmation of clinical effectiveness,” writes Emanuel, the co-director of the Healthcare Transformation Institute at the University of Pennsylvania. “Although, in some cases, this may be because the trials are of rare diseases for which there are few patients, it likely also reflects a disincentive to reach completion.”

To cover the topic of accelerated approvals, journalists need to have a good grasp of the different paths the FDA has for approving drugs.

In this article we’ll explain:

- The FDA’s traditional drug approval process.

- How accelerated approval works – including examples of successes and controversies.

- The difference between the FDA’s accelerated approvals and the emergency use authorizations the agency used to speed up the distribution of COVID-19 vaccines.

- The controversy surrounding Aduhelm and its complicated path to approval.

Finally, we’ll offer reporting tips for journalists who are covering stories about drugs cleared by accelerated approvals.

FDA’s drug approval processes

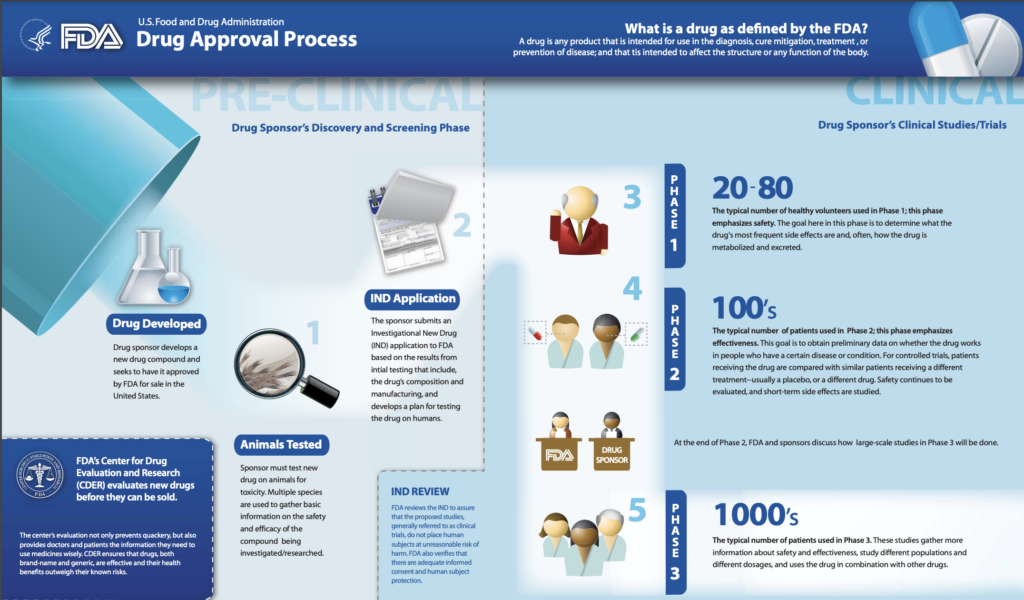

The ideal application for full FDA approval of a drug is built on robust results from two large well-designed studies of the experimental medicine. These kinds of studies are known as Phase 3 trials, reflecting the third of three key steps in medical trials of new drugs.

Phase 1 studies start with perhaps 20 to 80 people, usually people in good health. This step is intended to see if a medicine is safe enough for further testing. Phase 2 studies may involve hundreds of patients. These can give a good preview of how a medicine works, sometimes by measuring surrogate endpoints to get a quick read. These studies often enroll hundreds of patients. In Phase 3, medicines are often tested in thousands and even tens of thousands of patients.

However, there are alternate pathways to the full approval process – namely emergency use authorizations and accelerated approvals.

Emergency Use Authorizations (EUAs)

The FDA has several options for speeding medicines to market in urgent cases. In the case of COVID-19, for example, the FDA has granted special clearances known as emergency use authorization (EUAs) to products that have not yet been approved for U.S. sales.

EUAs are meant to aid in the response to events for which the federal government declares a public health emergency, such as the COVID-19 pandemic or a response to bioterrorism, such as an anthrax attack. EUAs can expire before or after the federal government deems that this event has ended. For example, the FDA in 2010 terminated EUAs for tests for detecting the H1N1 virus that had been granted when that flu posed a national threat.

The FDA in December 2020 used an EUA to clear the first COVID-19 vaccine, the one developed by BioNTech and Pfizer Inc. The key study on which this EUA rested counted cases of infection among study participants, of whom 18,198 received the vaccine and 18,325 received a placebo. The vaccine was judged 95% effective in preventing COVID-19 disease among these clinical trial participants, with eight COVID-19 cases in the vaccine group and 162 in the placebo group.

Pfizer in May submitted additional data on the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine and requested a full traditional approval. The FDA granted this in August. Moderna and J&J have plans to secure full approval of their vaccines as well. As with Pfizer’s application, the Moderna and J&J applications likely will provide additional information about how well their shots protect against COVID-19.

In all of these cases, the drugmakers presented the FDA with evidence about meaningful clinical outcomes such as their vaccines’ ability to prevent hospitalizations due to SARS-Cov-2 infection.

Accelerated approvals: Clear successes, stumbles and battles with drugmakers

The FDA has used accelerated approvals since 1992 in cases where there are few or no other options for treating serious and fatal diseases. The first medicine given one of these conditional clearances was an HIV drug.

Remember that accelerated approvals are based on surrogate markers: data that suggest – but have not yet proven – that the drug will provide a meaningful benefit or clinical outcome, with the expectation that the drugmaker will be able to demonstrate a clinical outcome in the future.

Sometimes companies can quickly prove to the FDA that their medicines merit full approval.

The FDA in 2020 granted accelerated approval for Gilead Sciences’ drug Trodelvy for a form of breast cancer that has spread to other parts of the body. The FDA said this conditional clearance was based on a study of 108 patients that judged how many patients had notable tumor shrinkage. In April 2021, the FDA granted full approval based on additional data that suggested the drug helps patients live longer.

In other cases, it can take years before results of trials conducted to confirm the expected benefits of a medicine are known.

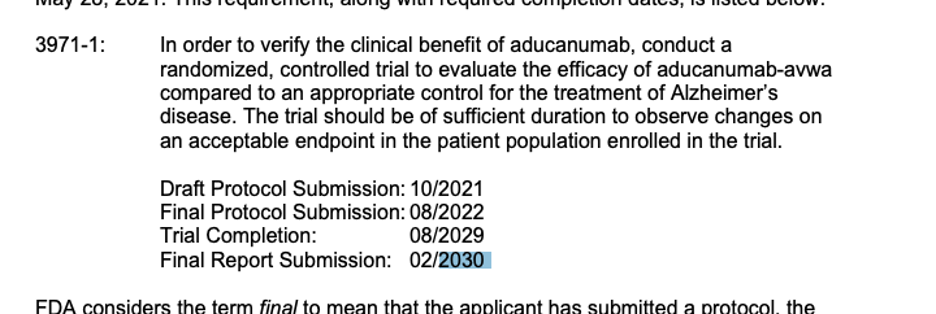

In the case of Aduhelm, the FDA has given Biogen until 2030 to deliver proof that the drug’s action on amyloid plaques will translate into a meaningful benefit such as delaying the toll of Alzheimer’s disease.

Drugmakers sometimes struggle to meet the deadlines set by the FDA. For example, the FDA in 2016 gave an accelerated approval for Sarepta Therapeutics Inc.’s drug Exondys 51 for Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a rare condition that is linked to a genetic mutation.

In the letter announcing the accelerated approval, the FDA gave Sarepta a 2021 deadline for delivering results of what’s called a confirmatory trial, a study done to test whether a drug can actually demonstrate an expected benefit. In this case, the FDA wants test results showing the drug help preserve motor skills in children with Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

But the FDA has accepted Sarepta’s delays in completing this work. The key trial of the drug is now expected to finish around 2026, according to a posting on the National Institutes of Health’s ClinicalTrial.gov site.

In a few cases, companies have pulled from the market drugs cleared through accelerated approvals. The FDA in 2016 granted an accelerated approval for Eli Lilly & Co.’s Lartruvo for a rare cancer called soft-tissue sarcoma. The approval rested on a study of 133 patients that suggested the drug helped patients live longer. But a larger study involving 509 patients failed to confirm this expected benefit. In 2019, Lilly asked the FDA to withdraw the approval, which the agency did in 2020.

In medical terminology, the uses of drugs for treating diseases are commonly known as “indications.” It’s important to note that one drug can receive multiple FDA approvals – a separate approval for each use. The FDA’s withdrawal of an indication for a medicine doesn’t affect other approved uses of that medicine.

Companies sometimes resist the FDA’s demand for a withdrawal of an indication. For example, the FDA granted accelerated approval in 2011 for the drug Makena, now owned by AMAG Pharmaceuticals, as a means of reducing risk of preterm birth in certain women.

The FDA required a larger study as part of accelerated approval. The follow-on study of about 1700 women marked a setback for Makena. The FDA in 2020 sought the withdrawal of the product from the market, citing disappointing results of a confirmatory trial. AMAG has not agreed. The FDA in August said it will hold a public hearing on this case, which had not been scheduled as of late September.

One of the most prolonged battles of this kind was Genentech’s resistance to the FDA’s calls for a withdrawal of the approval of its Avastin medicine for breast cancer, as described by reporter Rob Stein in a 2011 Washington Post story.

Then FDA Commissioner Margaret A. Hamburg in 2011 revoked the agency’s approval of the breast cancer indication for Avastin after concluding that the drug has not been shown to be safe and effective for that use. The drug remained on the market, as it was approved for other cancers. Studies found that Avastin raised the risk of serious bleeding, heart attacks and other problems, the FDA said.

“Sometimes, despite the hopes of investigators, patients, industry and even the FDA itself, the results of rigorous testing can be disappointing,” Hamburg said in a statement. “This is the case with Avastin when used for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer.”

An industry-wide evaluation of accelerated approval for cancer drugs

The FDA has sped up the pace of accelerated approvals in recent years, largely for both clearing sales of cancer drugs and then for additional uses of these oncology medicines.

The FDA now is in the midst of what it calls an “industry-wide evaluation” of accelerated approvals for certain cancer drugs. This evaluation centers largely on checkpoint inhibitors — drugs intended to unmask a mechanism tumor cells use to evade detection by the body’s immune system, which would otherwise attack and destroy them, as described by the National Cancer Institute.

In recent months, there have been multiple withdrawals of additional indications granted for checkpoint inhibitors, note the FDA’s top cancer-drug regulators in an May article in the New England Journal of Medicine, titled “‘Dangling’ Accelerated Approvals in Oncology.”

Drs. Julia Beaver, chief of medical oncology at the FDA, and Richard Pazdur, director of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence, describe 10 cases where required follow-on studies did not confirm expected benefits for checkpoint inhibitor drugs. Drugmakers have withdrawn in recent months at least six of the indications for at least four drugs questioned by the FDA staff, but these medicines remain on the market. Beaver and Pazdur note that most accelerated approvals have remained in place, citing this as a strength of the program.

“The small percentage of drugs whose clinical benefit is ultimately not confirmed should be viewed not as a failure of accelerated approval but rather as an expected trade-off in expediting drug development that benefits patients with severe or life-threatening diseases,” they write.

Researchers outside of the agency who have studied the FDA’s accelerated approvals have drawn a somewhat different conclusion.

In a September article in The BMJ, Dr. Aaron S. Kesselheim, founder and head of Harvard University’s Program on Regulation, Therapeutics, and Law (PORTAL); Dr. Benjamin Rome, a health policy researcher who works within PORTAL; and Dr. Bishal Gyawali, an associate professor at Queen’s University of Medicine, report the findings of a study of how drugmakers respond to the FDA’s mandates on accelerated approvals. The researchers homed in on 18 indications for 10 cancer drugs for which post-approval trials failed to show an expected benefit, or for which studies were not completed.

Delays “in regulatory actions after negative confirmatory trials mean that patients will continue to use these therapies that lack evidence of clinical benefit,” the authors write in their article, titled “Regulatory and clinical consequences of negative confirmatory trials of accelerated approval cancer drugs: retrospective observational study.”

“The FDA should take actions to assure that risks and benefits are clearly communicated to patients and their physicians, including the fact that some of the approvals remain on the label despite the negative results from the confirmatory trials,” they add.

Gyawali addresses this same issue in plainer language in an Aug. 4 commentary in Medscape Medical News. He argues for a need to maintain the focus of pharmaceutical research on finding medicines that help patients live longer or better.

“An unmet need doesn’t imply that the treatment void should be filled with a drug that provides nothing of value to patients,” writes Gyawali.

The complicated case of Aduhelm

To reiterate, the usual path for an accelerated approval involves a company presenting the FDA with evidence suggesting a benefit of its medicine for people with a serious disease and promising to do larger studies to confirm the benefit.

With Aduhelm, though, the trajectory to approval was convoluted.

Biogen initially set out to win full approval of the drug, based on a paired set of Phase 3 trials for Aduhelm. In March 2019, Biogen announced that the studies had failed, but in October of that year, the company updated its stance. The company said the results for patients treated with a higher dose of the drug in one of its two studies meet the benchmark for success. It sought to make a case for full approval of Aduhelm based on a reevaluation of this study.

The FDA has advisory committees for different medical specialties, allowing it to draw expert feedback when needed on whether to approve drugs and devices. At a November 2020 meeting, members of the FDA’s advisory committee that focuses on drugs that affect the nervous system disagreed with Biogen’s view of Aduhelm. Asked by the FDA to vote on a question of whether findings of this study proved the effectiveness of Aduhelm, 10 panelists voted “no” and one choose an option of “uncertain.” No panelists voted “yes.”

The FDA is not bound by the recommendations of this panel or any other of its advisory committees, although it usually follows their advice. In this case, the agency’s leadership in June 2021 granted an accelerated approval to Aduhlem, in spite of the advisory committee’s vote.

Biogen officials argue that patients need access to Aduhelm while it continues research on the drug. Otherwise, many people could see their illness progress to a point where Aduhelm would not be expected to help, Dr. Alfred Sandrock, Biogen’s head of research, argued in a July 22 statement.

Several FDA officials worked with the company to keep the application on track, reported Adam Feuerstein, Matthew Herper and Damian Garde in a June STAT article, “Inside ‘Project Onyx’: How Biogen used an FDA back channel to win approval of its polarizing Alzheimer’s drug.”

Following the FDA’s June approval of Aduhelm, three physicians resigned from the advisory committee on neurologic drugs: Dr. David S. Knopman, a clinical neurologist at the Mayo Clinic, Dr. Joel S. Perlmutter, a neurologist at Washington University and Harvard’s Kesselheim.

Other members of the FDA panel that reviewed Aduhelm also have publicly criticized the agency’s decision. Four other researchers who have served on the agency’s committee on neurologic drugs joined Knopman, Perlmutter and Kesselheim in writing a July perspective article in the New England Journal of Medicine, titled “Revisiting FDA Approval of Aducanumab.” (Aducanumab is the drug’s scientific name.) The other authors of this article were Dr. G. Caleb Alexander, Dr. Scott S. Emerson, Dr. Bruce Ovbiagele and Richard J. Kryscio.

In this paper, they note rising doubt about whether Aduhlem’s reduction of amyloid plaque has any meaningful benefit for people with Alzheimer’s disease.

Researchers have long theorized that abnormal levels of amyloid, a naturally occurring protein, disrupt cell function when they clump together, as the National Institute of Aging explains on its website.

But there’s debate about whether amyloid is the chief culprit in Alzheimer’s disease, note Knopman, Perlmutter, Kesselheim and co-authors in their NEJM article. Although there’s been significant work in recent decades targeting amyloid, more than two dozen therapies based on this theory have advanced as far as testing in patients, none of which produced a meaningful benefit for patients, they write.

The authors write that it’s “hard to reconcile the lack of convincing clinical benefit” seen in Aduhelm trials done to date with an “expectation of some clinical benefit of unknown magnitude” for people with Alzheimer’s disease.

“The overwhelming unmet need in this common and devastating disease should drive research investments, not lowering of regulatory standards that Americans rely on for safe and effective medicines,” they write.

Tips for journalists on covering medicines sold under accelerated approvals

1. If you’re reporting on a drug, note whether it has been granted an accelerated approval.

Members of the public may not realize how the FDA’s rules have changed over the years to speed medicines to market, says Diana Zuckerman, founder and president of the nonprofit National Center for Health Research, which both does its own research and analyzes studies done by others on medical treatments. Zuckerman emphasizes the need to make it clear in stories when the FDA cleared a drug based on limited evidence. “People need to understand that the standards are much lower than they used to be,” she says.

Indeed, many patients may not know their medicines have only conditional clearances, according to a September policy paper published in The Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research. Titled “Potential policy reforms to strengthen the accelerated approval pathway,” the paper was authored by Anna Kaltenboeck, program director of the Center for Health Policy and Outcomes at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Amanda Mehlman, director of strategic partnerships at the Institute for Clinical & Economic Review (ICER) and Dr. Steven D. Pearson, the founder and president of ICER. In their report, they emphasize a need to use ”simplified language accessible to a lay audience” in explaining accelerated approvals. The paper is an excellent resource for reporters getting up to speed on this issue.

2. Tell your audience what deadlines and terms the FDA has set as part of the accelerated approval of any given drug.

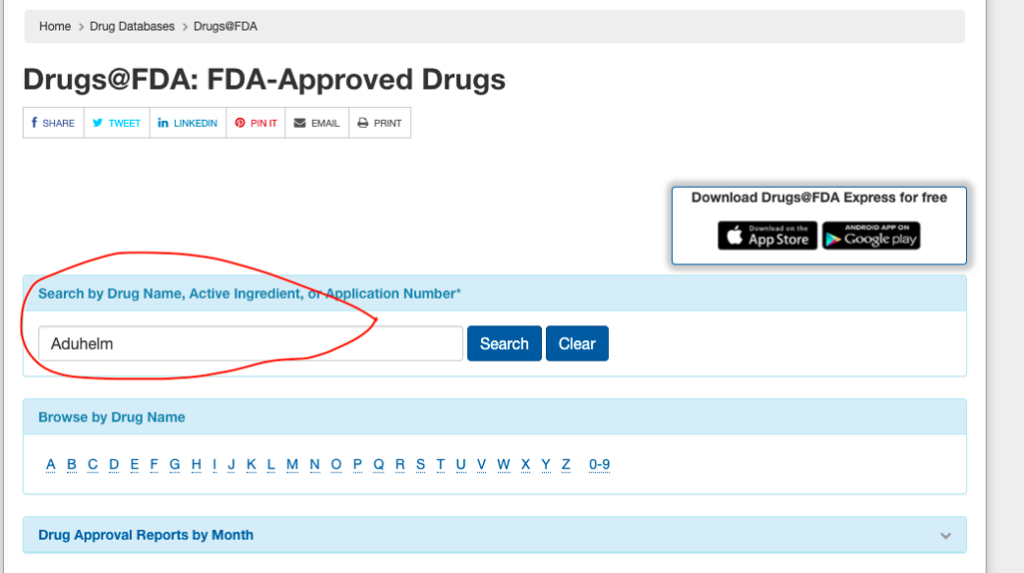

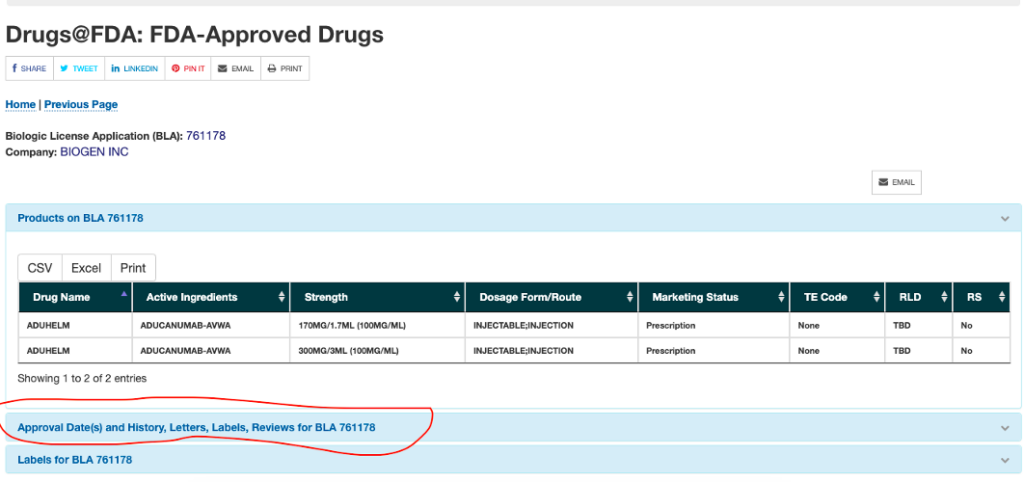

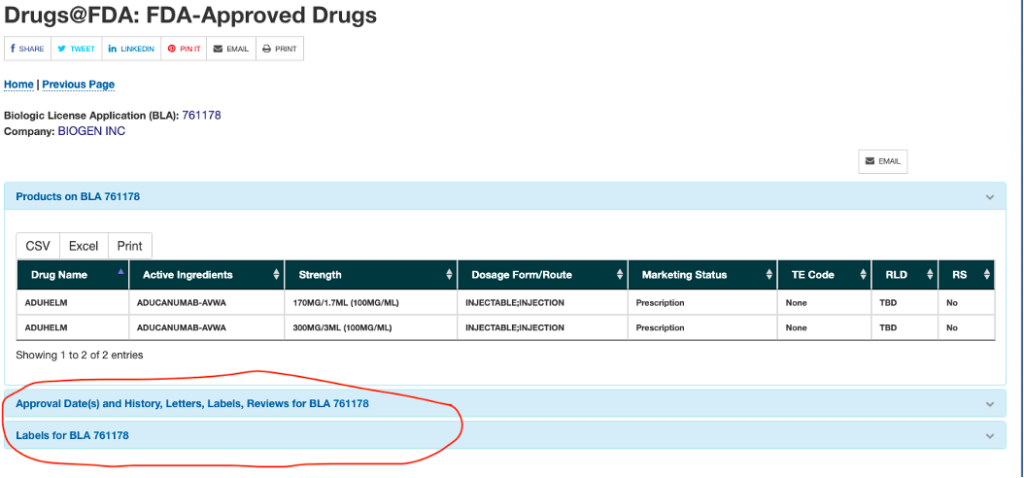

You can find this information on the FDA’s website. We’ll use Aduhelm as an example, with screenshots from the FDA site.

First, go to the FDA’s Drugs@FDA website and enter the name of the medicine in question.

Next, click on the link for the approval letter.

Finally, read the letter and find the details on the requirement for the confirmatory study, which include the deadline dates.

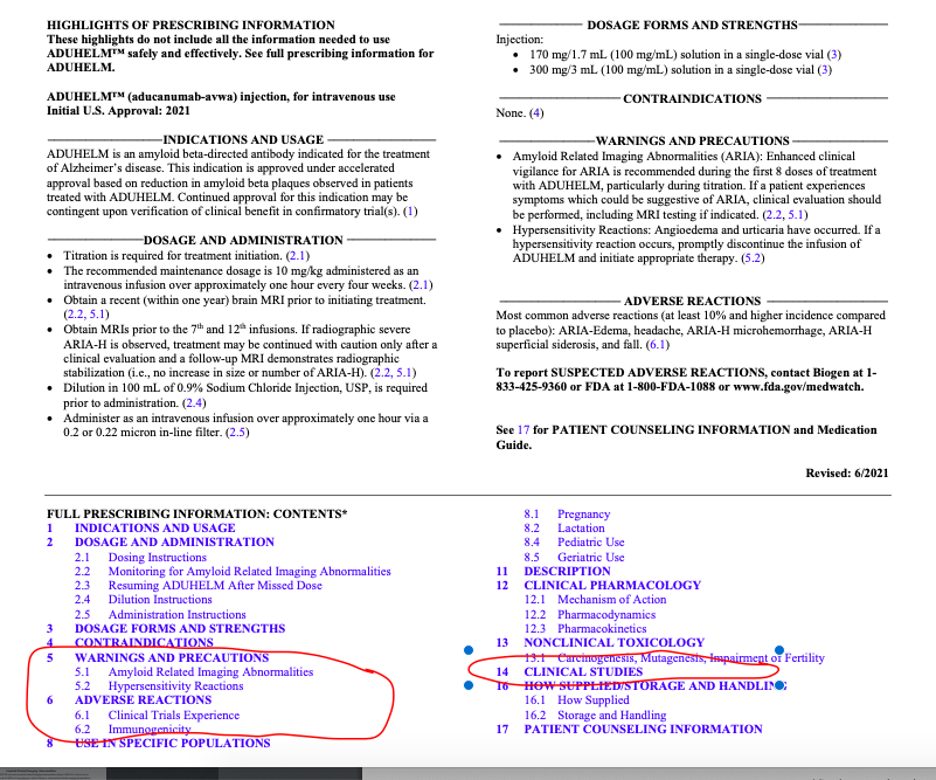

3. Clearly describe the potential side effects and potential benefits of drugs about which you report. You can find these details on the prescribing label for the medicine.

It can be helpful to give your audience a link to a drug’s prescribing label, whether a medicine was given an accelerated or a full approval. At a minimum, journalists should always take a look at the label for any drug about which they report.

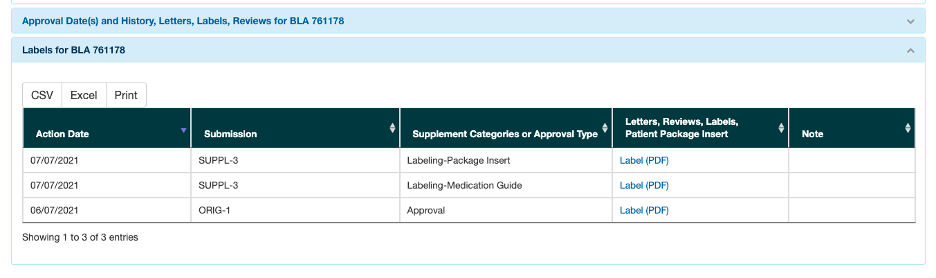

You can find the labels through that same FDA website. We’ll use Aduhelm again as an example. As seen in the screenshot below, you can find the label under the section with the approval dates and letters.

Clicking on the “Labels for BLA 761178” brings you to the following screen. The supplemental guides can be very helpful in translating medical jargon for your audience. But it’s important to look at the label.

Pay attention to the sections on warnings and precautions, adverse reactions and clinical studies.

If you need help in understanding the information in the label, reach out to an expert such as Zuckerman of the National Center for Health Research or Michael Carome, the director of the Health Research Group at Public Citizen.

You can also look for doctors at local universities who may be familiar with the drug you’re covering. The National Institutes of Health’s website for searching medical journals, Pubmed.gov, is a great source for finding physicians and researchers to comment for your stories.

4. Note financial connections between the researchers and experts you quote and pharmaceutical companies.

Let your audience know if a researcher or a physician has done consulting work or has a financial relationship with pharmaceutical companies. These connections don’t necessarily sway their judgment, but they can have an influence.

A good way to prepare for interviews with doctors is to check the federal OpenPayments database. This is managed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS.) It allows searches of reports drugmakers have submitted to CMS about payments they have made to physicians through research grants and speaking fees, as well as meal expenses. Ask the doctors if they agree with what CMS has reported because there can be errors in any database.

5. When reporting FDA data on accelerated approvals, note that the “total approvals” tally refers to the number of indications, not to the number of drugs.

The agency issues public reports on its accelerated approvals twice a year.

In the June 2021 report, the FDA reports a tally of 269 “total approvals.” But in some cases, this tally refers to multiple approvals given to one drug. An analysis of the FDA’s chart for this article found the names of about 160 different drugs, some of which had multiple approvals for multiple uses.

Further reading

A Middle Ground for Accelerated Drug Approval—Lessons From Aducanumab, Ezekiel J. Emanuel, JAMA, Sept. 23, 2021

“Dangling” Accelerated Approvals in Oncology, Julia A. Beaver and Richard Pazdur, New England Journal of Medicine, May 2021

Ensuring that accelerated approvals benefit patients, Editorial, The Lancet Haematology, September 2021

Regulatory and clinical consequences of negative confirmatory trials of accelerated approval cancer drugs: retrospective observational study, Bishal Gyawali; et al. The BMJ, September 2021.

Accelerated Approval of Cancer Drugs—Righting the Ship of the US Food and Drug Administration, Sarah S. P. DiMagno; et al. JAMA Internal Medicine, May 2019. This paper is a commentary on these two research articles:

- An overview of cancer drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration based on the surrogate end point of response rate, Emerson Y. Chen; et al. JAMA Internal Medicine, May 2019.

- Assessment of the Clinical Benefit of Cancer Drugs Receiving Accelerated Approval, Bishal Gyawali; et al. JAMA Internal Medicine, May 2019.

A 25-Year Experience of US Food and Drug Administration Accelerated Approval of Malignant Hematology and Oncology Drugs and Biologics: A Review, Julia A Beaver et; et al. JAMA Oncology, June 2018.

Also, for those new to covering the FDA, there is a free online course available through EdX on the agency’s approvals of medicines, Prescription Drug Regulation, Cost, and Access: Current Controversies in Context. It is led by Kesselheim, who has published many papers on the FDA’s handling of drug approvals.

Expert Commentary