Health warning labels that use strong causal language deter consumers more than labels with weaker language, a new study in the American Journal of Public Health finds.

The findings lend support to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s proposed cigarette warning labels, issued August 15, 2019, which feature illustrations of health risks associated with smoking and strong causal language such as “smoking causes head and neck cancer.”

Frequent readers of Journalist’s Resource might note that we’ve stressed again and again the importance of not implying causation when research merely suggests correlation. But that’s not the case here. A large body of research has shown that smoking does, in fact, cause cancer.

“We are very supportive of this kind of language that FDA is using, given that there’s a lot of strong epidemiological evidence supporting those causal links between smoking and the health effects,” explains the study’s lead author Marissa Hall, an assistant professor in the department of health behavior at the University of North Carolina. “It’s justifiable based on the evidence, and it does actually matter in terms of how effective these are likely to be.”

The study surveyed 1,360 adults across the U.S. through Amazon Mechanical Turk about their responses to health warnings for cigarettes, sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) or alcohol. Participants took the survey online and viewed four warnings, listed here in descending order of strength: “causes,” “contributes to,” “can contribute to,” and “may contribute to.”

For example, cigarette warnings would substitute the variants into the following: “WARNING: Smoking cigarettes [____ __] lung cancer.” Sugar-sweetened beverage warnings cautioned about tooth decay, and alcohol warnings referred to liver disease.

Participants were then asked which warning would most discourage them from wanting to use the product, which would least discourage them, and which they most supported implementing. For each question, the respondents were presented again with the four variants of the warnings they had previously viewed.

“My background is mostly in tobacco control policy and warning labels. And what we’ve noticed is that there’s just a lot of variety in the kinds of causal language that’s used in different warnings across different products,” Hall says. “I had this real interest in understanding, what is the impact of different causal variations? Does that matter at all to the public? It’s possible that people don’t really care whether it says ‘causes’ versus ‘contributes to’ versus ‘may contribute to.’ But the study found that it really does actually matter, and is likely to change the impact of the warnings.”

The findings

The researchers found 76% of participants selected the warning that used the strongest language (“causes”) as the one that most discouraged potential use. It was also the language most participants (39%) supported using for a warning. The least discouraging warning label, according to 66% of participants, used the weakest causal language (“may contribute to”).

Across the products studied, there were small differences in the likelihood that participants would select “causes” as the most discouraging warning and as the label they would most likely support for use on the product. Participants were slightly less likely to favor the strongest causal language for warnings on alcohol and sugar-sweetened beverages than for cigarettes.

“Which isn’t surprising,” Hall adds, “given that people are used to seeing cigarette warnings, and there’s, more of a track record. For example, cigarette warnings have been required in the U.S. for several decades, where they’re not yet required for sugar-sweetened beverages. And alcohol warnings tend to be just one text warning that’s pretty small and hard to notice.”

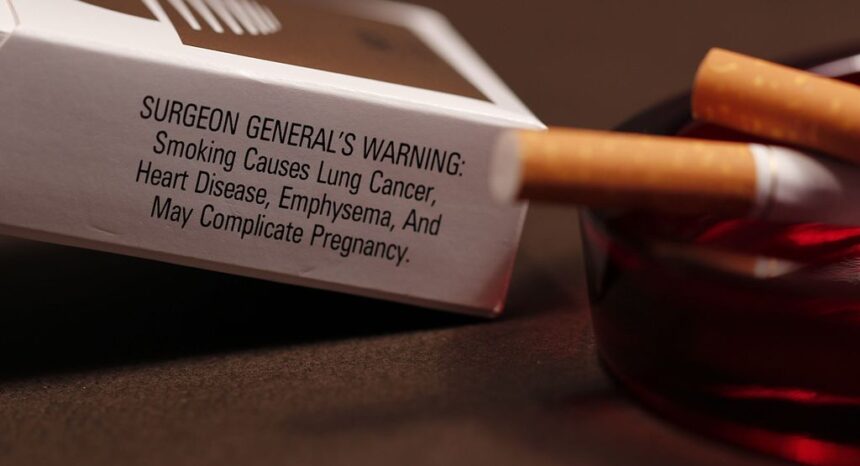

In the U.S., cigarettes packages have a warning stating “Smoking causes lung cancer, heart disease, emphysema, and may complicate pregnancy.” Warning labels for cigarettes have been required in the U.S. since 1966.

The Alcoholic Beverage Labeling Act (ABLA) of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988, requires alcoholic beverages to warn:

“(1) According to the Surgeon General, women should not drink alcoholic beverages during pregnancy because of the risk of birth defects. (2) Consumption of alcoholic beverages impairs your ability to drive a car or operate machinery, and may cause health problems.”

There are no federal policies that require warning labels for sugar-sweetened beverages, though individual states, like California, are pursuing initiatives.

One limitation of the new study is that it only looks at survey responses, and not the real-life effects on customers’ consumption habits if they were to encounter the warnings in retail outlets. However, Hall notes that one of the questions they studied — which warning would most discourage wanting to use the product — is “highly predictive” of behavioral change, as shown by other studies.

“I would love for future studies to replicate these findings with behavioral outcomes. And I think that would be a logical next step,” Hall adds.

Moreover, she notes that there’s already clinical research suggesting another kind of warning — pictorial warning labels — on cigarettes have successfully deterred people with established smoking habits.

Usable info for policymakers and journalists

Hall notes that policymakers and journalists alike can use these findings in their work.

Journalists, she says, might consider discussing the risks of products like cigarettes, alcohol and sugar-sweetened beverages as a matter of course in their reporting, whether the coverage is critical or lifestyle-focused.

“The typical person is not going to be reading AJPH on a regular basis,” she says. “So, yeah, talking about the background, what are the risks, leading up to stories that you’re covering, that seems great.”

And policymakers can use the findings to inform labeling efforts. “I think that policymakers have to really look at the research to inform the way they’re designing warnings. And so this is one way that the research, I hope, can then inform policymakers who are trying to weigh the pros and cons of different types of warnings and causal language,” she says.

Legislators backing warning labels might face legal challenges related to the First Amendment issue. “The issue really rests on compelled commercial speech, which refers to the government’s ability to require companies to put language on their products,” Hall explains. “And so there are really high standards and very specific standards for what’s allowable.”

In 2015, for example, the city of San Francisco enacted a sugar-sweetened beverage warning ordinance, which required ads for sugar-sweetened beverages to convey the following — “WARNING: Drinking beverages with added sugar(s) contributes to obesity, diabetes, and tooth decay.”

It was subsequently challenged in court by the American Beverage Association, reaching the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. The court ruled in the Association’s favor. As a result, the city has proposed modified warning text, which reads: “Drinking beverages with added sugar(s) may contribute to obesity, type 2 diabetes, and tooth decay.”

The key changes are the softening of “contributes to” to “may contribute to,” as well as specifying that the risk for diabetes is restricted to type 2 diabetes.

“San Francisco’s compelled message is problematic because it suggests that sugar is always dangerous for diabetics. In fact, consuming sugar-sweetened beverages can be medically indicated for a type 1 diabetic when there are signs of hypoglycemia, a complication of type 1 diabetes, because drinking fruit juice or soda raises blood sugar levels quickly,” the court’s ruling reads.

But Hall is disappointed by the notion of softening the proposed warning with the word ‘may.’

“I have read the meta-analyses and systematic reviews of longitudinal cohort studies show that these linkages are very factual. So it’s quite surprising to me that they’ve been questioned, and I think that it’s clear that the warning is not saying that every single person who drinks an SSB will inherently get type two diabetes. That’s not what the warnings are saying,” Hall says. “It’s disappointing to see the courts moving in this direction. To me, that’s questioning strong scientific evidence that we have, and making us weasel-word our way around warnings and weaken their meaning.”

The image on this page, obtained from Wikimedia Commons, is being used under a Creative Commons license. No changes were made.

Expert Commentary