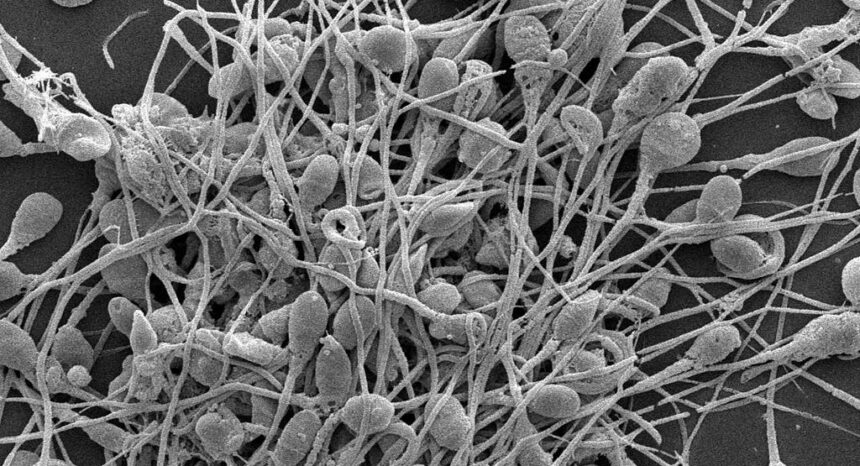

For several decades, researchers have warned that modern lifestyles may be killing off sperm. Specifically, researchers have noted concern about the endocrine-disrupting chemicals found in many products — pesticides, sunblock, plastic water bottles, non-stick pans — that mimic sex hormones and confuse our bodies.

But despite hundreds of papers on sperm counts and quality, there has been little consensus on a trend.

A new paper aims to move the debate forward: It analyzes almost four decades of research and concludes that sperm counts are indeed falling precipitously, show no sign of slowing, and require urgent attention.

An academic study worth reading: “Temporal Trends in Sperm Count: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis,” in Human Reproduction Update, 2017.

Study summary: Hagai Levine of Hadassah-Hebrew University in Israel and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York led a team of eight international scholars to sift through research on sperm counts since the early 1970s. They analyzed over 7,500 peer-reviewed papers that had each collected original data using two different methods — human sperm concentration (SC) and total sperm count (TSC). The authors narrowed down their search to 185 papers with 244 datasets on almost 43,000 men around the world who had provided semen samples between 1973 and 2011.

Levine and his team then broke these studies into two geographic groups: Western (men from North America, Europe, Australia and New Zealand) and non-Western (men from South America, Asia and Africa). They also classified the men either as “fertile,” when the men were known to have caused a pregnancy (104 of the datasets), or “unselected for fertility,” when researchers had no data on the man’s fecundity (140 data sets; usually young men). The researchers discarded studies that included men with known fertility complications or who were known to smoke, since smoking appears to lower sperm count.

Key takeaways:

- Western men unselected for fertility saw SC decline 52.4 percent between 1973 and 2011 (1.4 percent per year). Over the same years, the same men saw TSC decline 59.3 percent (1.6 percent per year).

- For all men included in the data, SC and TSC fell 0.75 percent per year, or 28.5 percent between 1973 and 2011.

- The researchers found no significant trends for non-Western men, though they believe this may be due to a paucity of data.

- Semen volume did not change significantly.

- When the authors performed sensitivity tests (cutting certain data and ensuring data was not weighed too heavily toward any one population or country), they found little change in the rate that sperm counts are falling. Looking only at recent years, in other words, there is no sign the decline is slowing or leveling off.

Helpful resources:

The National Institutes of Health has this introduction on endocrine disruptors and describes some of the consumer products that may be responsible. The World Health Organization has similar resources.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office on Women’s Health has a list of frequently asked questions on infertility, including information on infertility in men.

The National Centers for Translational Research in Reproduction and Infertility are government-funded research labs at some of America’s top universities.

The UN publishes data on fertility around the world.

Other research:

A lower sperm count than average is associated with testicular cancer, according to this 2016 paper, and early death according to this 2009 paper.

A 2017 paper in the American Journal of Epidemiology found that men with lower sperm counts were more likely to be hospitalized and to develop cardiovascular disease.

The family members of men with poor semen quality (low counts and higher proportions of deformed sperm) have higher risks of testicular and thyroid cancer, according to this 2016 paper. A 2017 paper in Human Reproduction found first-degree relatives of men with low sperm counts face higher risks of childhood mortality.

A 2017 study of men in the Baltic states found lower sperm counts among smokers; many other papers, such as this 2016 study by the European Association of Urology, found similar results.

This 2009 paper is a defining statement on the role of endocrine disrupters in human reproduction. Journalist’s Resource also covered endocrine disruptors here.

Expert Commentary