The year 2016 was the hottest ever recorded, marking the third consecutive year of record warm temperatures on the Earth’s surface, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and NASA. Of the 17 hottest years in history, 16 have been since 2000. Scientists are unequivocal: we humans are behind global warming.

As a result, polar ice is melting and the seas are rising faster than at any time in at least 2,800 years. The sea level has climbed by up to nine inches since 1880 and by three inches since 1993, according to research published in Nature.

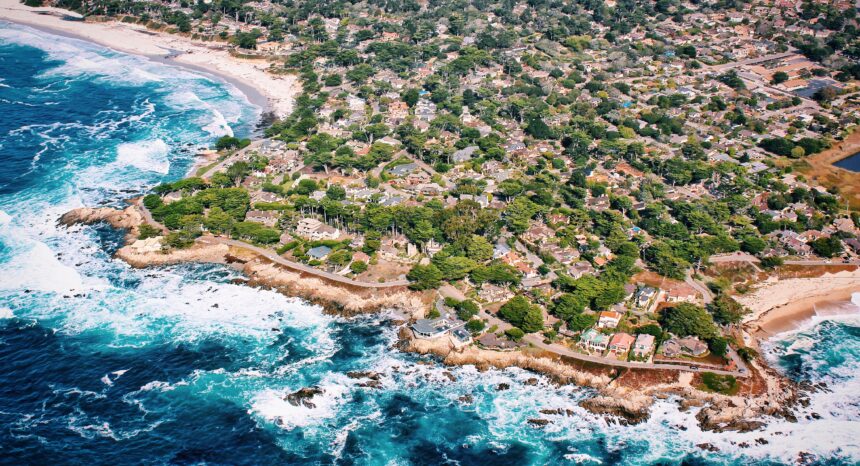

For Americans living near the coasts and wondering how long before their homes are inundated, a new NOAA report — released on the last day of Barack Obama’s administration — offers region-specific predictions to help them prepare.

A report worth reading: “Global and Regional Sea Level Rise Scenarios for the United States,” published by NOAA on January 19, 2017.

Ocean currents can influence how much the sea is rising in different places. The shifting weight of the seas as polar ice melts can reshape the earth’s crust, change the planet’s gravitational field and rotation, and the shape of the ocean basin. All this affects how we measure what scientists call “gridded relative sea level,” or RSL, and explains why some regions are more vulnerable to rising seas than others.

“The ocean is not rising like water would in a bathtub,” lead author William Sweet of NOAA said in a press release announcing the 75-page report. “For example, in some scenarios sea levels in the Pacific Northwest are expected to rise slower than the global average, but in the Northeast they are expected to rise faster.”

NOAA created six models for each of the next eight decades, or until the year 2100, and projected them onto sections of coastline about 70 miles long. That allows policymakers in different regions to use the same models. The models — called low, intermediate-low, intermediate, intermediate-high, high and extreme — correspond to sea level rises of 0.3, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0 and 2.5 meters respectively (approximately 1 to 8 feet).

Key takeaways:

- The authors expect the global average sea level to rise at least 0.3 meters (about 1 foot) by 2100.

- A sea level rise of 2 to 2.7 meters by 2100, due to rapid Antarctic and Greenland ice melt, “may be more likely than previously thought.”

- A sea level rise of 0.9 meters would permanently flood areas home to 2 million Americans; 1.8 meters would permanently inundate areas home to 6 million.

- Under the likeliest scenarios, 90 major coastal cities like New York and Miami will see the chance of annual disruptive flooding (moderate floods that present “serious risk to life and property”) grow 25 times by 2080.

- From Virginia to Maine and in the western Gulf of Mexico, the rise in RSL is projected to be greater than the global average in almost all scenarios.

- In the Pacific Northwest and Alaska, the rise in RSL is projected to be less than the global average in the low-to-intermediate scenarios.

- Along almost all the coasts in the continental United States, the rise in RSL is projected to be higher than the global average under the three worst-case scenarios.

The report is available on the NOAA website. We have also archived it here.

Helpful resources:

The Pentagon in 2016 used methods similar to NOAA’s to assess sea level changes near military installations around the world.

The United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) examines and reports on the scientific research related to climate change. We profiled its 2014 report on “impacts, adaptation and vulnerability.”

NOAA publishes extensive data on weather and global warming in general, as well as more specific tools like maps that visualize coastal flooding related to rising seas.

A list of other government data sources on climate change is available here.

The federal government’s subsidized flood insurance program encourages residents to rebuild in areas affected by rising seas. Over the years, the program has spent tens of billions of taxpayer dollars, often in areas certain to be inundated again. The New York Times reported in 2012 on how the program has helped Dauphin Island in Alabama, one of the nation’s most vulnerable areas, rebuild over and over.

Other research:

Our 2016 research roundup examines climate change-related risks and the regions and demographic groups most threatened by them.

A 2016 study by Pew Research Center looks at how politicized the debate over climate science has become in America.

New York City can expect many more floods, according to this 2016 study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Expert Commentary