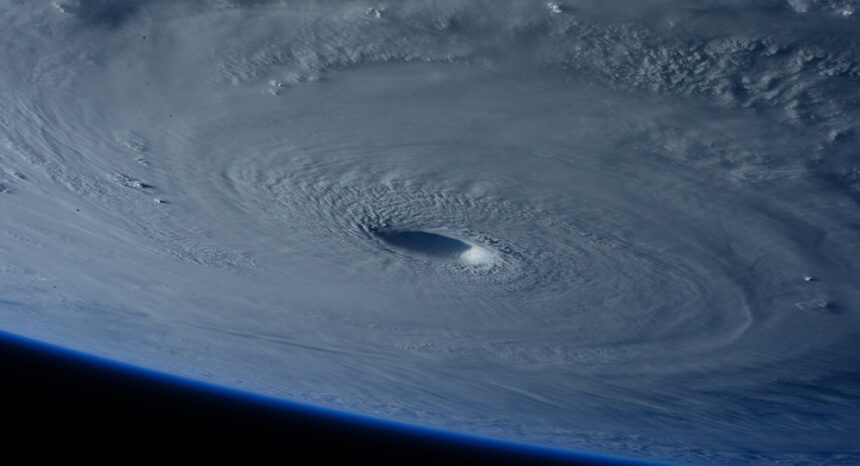

Giant hurricanes like Katrina and Sandy may be the new normal, according to research on how such storms are fortified by the changing climate and rising seas. But modeling the cost of future hurricane destruction is tricky. A new paper looks at the combined effect, over the next 60 years, of stronger storms and a growing population along America’s vulnerable East and Gulf coasts. It finds that cleanup will cost a small but growing share of economic output.

An academic study worth reading: “Projected Increases in Hurricane Damage in the United States: The Role of Climate Change and Coastal Development,” in Ecological Economics, 2017.

Study summary: Terry Dinan of the Congressional Budget Office simulates 5,000 hurricanes in the year 2075. Focusing on coastal states with “nonzero” chances of being hit by a hurricane, she compares the modeled damage with the type of destruction that has occurred in recent storms, large and small.

To estimate potential damage in 2075 she uses county-level data on both population growth and income to model the communities in that year. She also weighs these counties based on their relative vulnerability.

There are, of course, “significant underlying uncertainties about the effects of climate change on hurricane formation,” Dinan acknowledges. Yet what interests her is not the effect of one storm, but the economic impact when climate change, rising seas and coastal development are considered together.

Key takeaways:

- Dinan finds that the damage from hurricanes, measured as a share of economic output (GDP), will increase. That means not only that future hurricanes will cost more dollars to clean up, but that the cleanup will be harder for the country to afford. She expects the annual cost of damage, in constant 2015 dollars, to rise from an estimated $28 billion (0.16 percent of GDP) these days to $151 billion (0.22 percent of GDP) in 2075. She notes, however, that exact numbers are uncertain.

- The absolute damage will increase because Americans are building more and denser communities along the coasts.

- Taken together, she estimates the increase in climate change-related hurricane damage and damage to new coastal development at $123 billion (the difference between $151 billion and $28 billion).

- That is a synergistic effect. Separating them, she finds damage from climate change increases by $35 billion; damage to the new coastal development increases by $41 billion.

- She estimates the value of hurricane damage to new coastal developments alone at $47 billion: “That $47 billion reflects the additional damage that climate change has on the additional property exposure attributable to coastal development.”

- By comparing the number of people currently living in counties facing “substantial” expected storm damage (defined as “expected per capita damage that is greater than 5 percent of the county’s average per capita income”) to the number of people expected in such counties in 2075, Dinan estimates that this at-risk population will grow eight-fold over the model period.

Helpful resources:

- The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is a U.S. government agency that, when funding allows, studies climate change. It also publishes data on how much the most ruinous hurricanes cost to clean up and runs the National Hurricane Center.

- NASA has a resource page on hurricanes and FEMA — the Federal Emergency Management Agency — has images.

- The Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the nonpartisan accounting arm of Congress, analyzes how climate change will impact the federal budget and how federal regulations could impact the climate.

- Our tip sheet on covering hurricanes is packed with resources for journalists.

Other research:

- This 2017 paper in Nature Climate Change models how Americans might migrate away from the coasts as seas rise.

- This 2017 paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research looks at how natural disasters such as hurricanes have impacted economic output in American counties over the past 100 years.

- This 2006 paper in Ecological Economics investigates, inter alia, how government-subsidized flood insurance has encouraged development among vulnerable coasts.

- This 2015 paper in Climactic Change examines the joint effects of storm surges and rising sea levels.

- We’ve profiled research on the demographics of who moves after a hurricane. Our 2016 literature review looks at rising seas and global adaptation strategies.

Expert Commentary