On July 6, 2018, Politico reported that top advisers at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency were suppressing a federal report on the health risks of formaldehyde. The article suggests these advisers are bending to industry interests opposed to the release of the report, which purportedly links formaldehyde exposure to the risk of developing leukemia.

A barrage of media coverage followed, reawakening concerns about a question scientists have been studying for a long time: What are the risks of formaldehyde exposure? And how much exposure constitutes a real risk?

According to the EPA’s Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS), which provides assessments of the health effects of environmental hazards, formaldehyde is considered a “probable human carcinogen” for certain respiratory cancers. This assessment was last updated in 1989. The EPA is working on an updated IRIS assessment of formaldehyde. The National Research Council of the National Academies peer-reviewed a prior draft assessment in 2011.

In a January 2018 report to Congress, the EPA pledged to deliver an external review draft of its assessment for public comment in fiscal year 2018, which ends on Sept. 30. The EPA has not yet released the report.

A May 17, 2018 letter from Sens. Edward J. Markey, Sheldon Whitehouse and Thomas R. Carper to then-EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt indicates that industry interests have stalled the report.

“We have also learned that, at the same time as EPA political appointees’ requests were delaying the formaldehyde assessment’s movement through the agency review process, the American Chemistry Council (ACC) as well as interested corporations such as ExxonMobil have been pressuring EPA not to release the assessment for public comment as drafted,” the letter states. “ACC, ExxonMobil and other industry actors are said by the individuals we have communicated with to particularly object to findings related to leukemia.”

In the meantime, for reporters looking to learn more about the link between formaldehyde and cancer, Journalist’s Resource interviewed several epidemiologists who have expertise in the subject. The scientific evidence supporting a link is strong, though the findings are complex and somewhat contested. Researchers suggest that the risks are greatest for those who work closely with the chemical and face high levels of exposure. And they take great care to clarify the difference between association and causation.

“We are epidemiologists and statisticians,” said Michael Hauptmann, head of the biostatistics group at the Netherlands Cancer Institute, in a phone interview with Journalist’s Resource. Hauptmann has authored several key studies that explore associations between formaldehyde and cancer risk. “We observe people as they are exposed and look at whether they have a higher incidence of certain cancers. We do not have the means to look at the mechanisms how formaldehyde might cause leukemia and other cancers. This is indeed still unknown for formaldehyde.”

Formaldehyde is a chemical used in a number of applications, from embalming to professional hair-smoothing treatments to the manufacture of plastics and composite wood products. It is a known carcinogen, according to both the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and the National Toxicology Program (NTP), which evaluated the evidence in support of a causal connection between formaldehyde exposure and nasopharyngeal cancer. The chemical enters the body most commonly through inhalation of formaldehyde gas or vapor. It is also associated with respiratory ailments including asthma, allergies and eye irritation.

The IARC and NTP reports both suggest an association between formaldehyde exposure and leukemia. The IARC report, last updated in 2018, states that epidemiologic evidence provides support for a causal connection between occupational exposure to formaldehyde and leukemia. By contrast, the NTP report stops short of such causal claims, but suggests an association between the two.

The research

First, there are a number of studies that have demonstrated positive associations between professionals who work closely with formaldehyde (e.g., embalmers and pathologists) and leukemia deaths. One study, however, did not find a positive association among radiologists and pathologists.

A 2009 study published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute found that embalmers who worked in the funeral industry for longer periods of time and who were exposed to formaldehyde at greater levels experienced elevated risk of death from myeloid leukemia as compared to peers in the industry who had shorter careers and less exposure to formaldehyde.

“In the embalmers study, we found a strong dose response between any metric of formaldehyde exposure,” lead author Hauptmann said in a phone interview with Journalist’s Resource. “You can measure the average intensity, or the cumulative exposure to formaldehyde, the time that you spend at a certain concentration of formaldehyde in the air, but also just the number of years you worked with formaldehyde or embalmings a person was doing. And for all these metrics we found a strong dose response with leukemia.”

Hauptmann also participated in the analysis of another formaldehyde study, published in 2003 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute. That study followed 25,619 industrial workers (producing formaldehyde, flooring, resins, plastics and other formaldehyde-related products) from January 1, 1966 through 1994. It also found an association between formaldehyde exposure and leukemia, which was strongest for those who were exposed to higher levels of formaldehyde during short-term exposures.

“From a research point of view, these were the two largest and best studies available so far,” said Hauptmann, who serves as a statistical editor for the Journal of the National Cancer Institute and the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Hauptmann, along with six other researchers, followed up on his 2003 study with another publication in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute in 2009. Again, the research found “statistically significant increased risks for the highest vs. lowest peak formaldehyde exposure category (≥4 parts per million [ppm] vs >0 to <2.0 ppm) and all lymphohematopoietic malignancies.”

The results, however, were not as strong in the follow-up study as in the 2003 analysis. Hauptmann and one of his co-authors, Laura Beane Freeman, an investigator at the National Cancer Institute, suggested to Journalist’s Resource that this is because the heaviest industrial exposure to formaldehyde took place prior to the 1980s. Leukemia has a shorter latency than 25 years, Beane Freeman said, and so she did not expect to see additional leukemia deaths in the follow-up with the industrial workers.

Another study of industrial workers exposed to formaldehyde (a large study of British chemical workers) published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute in 2003 did not find an association between formaldehyde exposure and mortality from leukemia. However, this study involved a smaller sample and did not evaluate either workers’ peak exposures or average exposure intensities.

Analysis and reanalysis

Beane Freeman and Hauptmann’s original analysis was reanalyzed by a group of scientists in a 2015 paper in the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. The reanalysis was funded by the American Chemistry Council (ACC), an industry trade association for American chemical companies.

Harvey Checkoway, an epidemiologist at the University of California, San Diego led the project. Checkoway told Journalist’s Resource that he has consulted for chemical companies and served on industry advisory panels as well.

“I know there are concerns in this situation and other situations if there’s so-called industry sponsorship that they can influence the results,” Checkoway said in a phone interview. The ACC, he said, was “totally hands off.”

The Checkoway analysis redefined peak exposure to formaldehyde on an absolute basis for all industry workers, rather than relative basis for each job.

Checkoway called the original metric a “very idiosyncratic definition of ‘peak’. We tried to come up with a more standard definition.”

But Hauptmann and Beane Freeman stand by their definition. “We made a very careful industrial assessment by exposure hygienists,” Hauptmann told Journalist’s Resource. “I wouldn’t say that one or the other is more idiosyncratic,” Beane Freeman said. The Beane Freeman/Hauptmann metric looked at workers’ average exposures to formaldehyde, and then looked for variations above that peak based on the tasks performed on the job.

“At some point you get a bit tired of these re-analyses and reviews and new reviews,” Hauptmann said. “There haven’t been any new epidemiological studies, really, in more than 10 years that have looked at this. So we’re talking about re-analyses of the same data by scientists with different agendas.”

In Checkoway’s analysis, “We saw sort of a glimmer of an association for overall leukemias, but not a whole lot for [acute myeloid leukemia],” he said.

Moreover, he suggested that “there’s not a lot of precedent” for malignancies to be associated with a peak exposure, as compared to cumulative exposure, though most of the research on formaldehyde supports an association with the former over the latter. There are a few exceptions, notably ionizing radiation and the chemical benzene.

Beane Freeman suggested the peak exposure association is biologically plausible. “Your body produces formaldehyde, so it can handle formaldehyde in some way,” she explained. In this sense, peak exposures might be more important insofar as they “overwhelm the body’s ability to handle” formaldehyde, as it does with endogenously occurring forms of the chemical.

Beane Freeman also pointed to evidence from the numerous studies of embalmers, who experience high, short-term exposures to formaldehyde in support of this theory.

More studies

The scholars contacted for this piece repeatedly stressed the importance of considering the totality of the evidence exploring associations between formaldehyde and leukemia risk when evaluating the substance.

Luoping Zhang, an adjunct professor of toxicology at University of California, Berkeley conducted a meta-analysis of 15 studies that looked at workers and professionals exposed to formaldehyde. The study was published in Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research in 2009. The meta-analysis differed from others in that it focused on looking at the highest exposure groups in each of the included studies. Other meta-analyses focused on formaldehyde exposure more generally instead of honing in on the groups with the highest levels of exposure. “We’re focused on highest exposure,” Zhang told Journalist’s Resource. “Because we think if there is an association, for the people exposed long enough [or at a high enough level], we should see an association. And we did.”

The meta-analysis found a significantly higher leukemia risk for those with high levels of formaldehyde exposure in the selected studies. In particular, the highest increases in relative risk were for acute myeloid leukemia.

Mechanism unknown

All the researchers contacted for this piece agreed that if there is an association between formaldehyde exposure and leukemia risk, a causal mechanism is not yet understood.

Zhang has begun research to gather biological evidence backing an association between formaldehyde exposure and leukemia risk. In 2010 she published with colleagues a paper in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention titled “Occupational Exposure to Formaldehyde, Hematotoxicity, and Leukemia-Specific Chromosome Changes in Cultured Myeloid Progenitor Cells.”

The study looked at 94 healthy workers in China, half of whom were exposed to formaldehyde and half of whom served as a control group. For those who were exposed, they found concerning biological signs: “Among exposed workers, peripheral blood cell counts were significantly lowered in a manner consistent with toxic effects on the bone marrow and leukemia-specific chromosome changes were significantly elevated in myeloid blood progenitor cells.”

Further, Zhang has conducted some animal research which established links between formaldehyde exposure and bone marrow toxicity in mice, which might help explain how exposure leads to the development of leukemia. However, the pathway through which formaldehyde exposure might cause bone marrow toxicity remains unknown.

Exposure among the general population

While some studies have found associations between high levels of formaldehyde exposure and leukemia mortality, the scholars interviewed for this piece agreed that lower levels of exposure likely pose lower risks.

“I think if you want to talk about the absolute health effects of formaldehyde exposure, I would say that they are probably not large, because formaldehyde doesn’t seem to be a strong carcinogen, and the exposure of people in the environment, general population levels, are relatively low,” Hauptmann said.

However, there have been a number of high profile cases of elevated levels of formaldehyde off-gassing in consumer products, including flooring from Lumber Liquidators and mobile homes provided to those displaced by Hurricane Katrina.

“The levels where we see risk for myeloid leukemia, these peak exposures are above 4 parts per million,” Beane Freeman said. “I would imagine that people are not walking around being exposed to 4 parts per million in the general population,” she added, explaining that indoor air with off-gassing products generally has formaldehyde levels in the range of 0.01-0.02 parts per million.

And though the link between leukemia and formaldehyde exposure remains contested, Zhang emphasized that the chemical’s association with nasopharyngeal cancer still merits “warning the general citizenry of America about the risks of chemical exposure.”

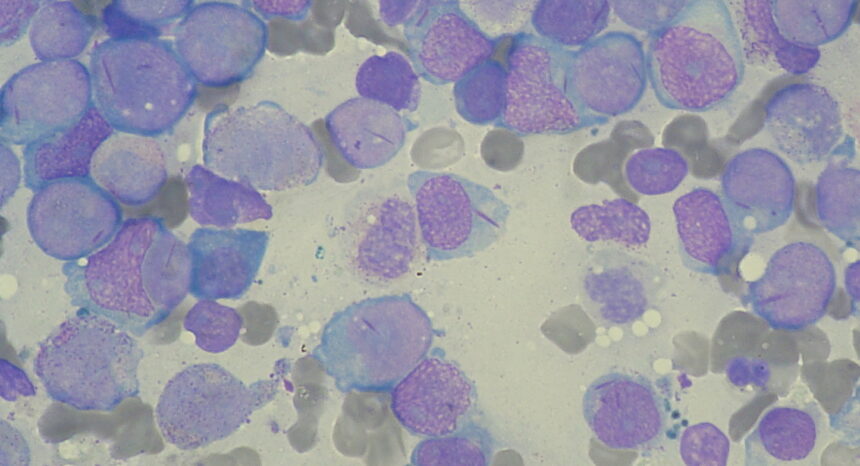

This photo, property of , was obtained from Wikimedia Commons and used under a Creative Commons license.

Expert Commentary