The crowd has wisdom, sure, but it also has capital. Sites like Kickstarter and GoFundMe allow everyone from upstart entrepreneurs to patients facing exorbitant medical bills to tap into these funds, and now academics are hopping on the bandwagon too.

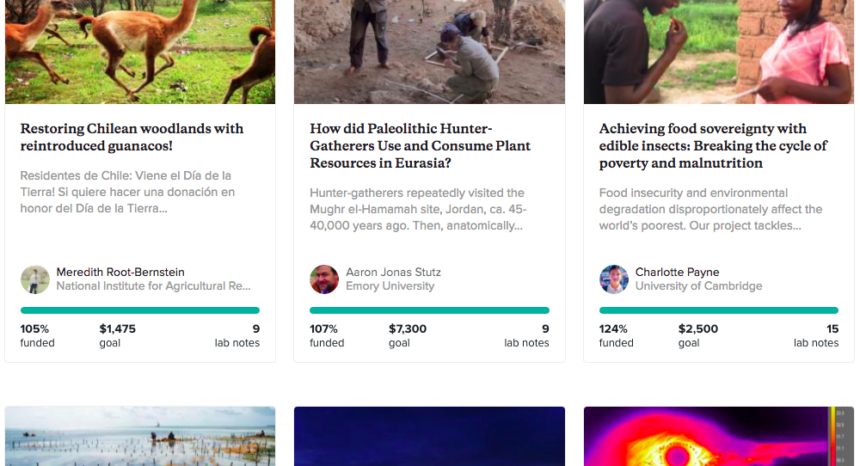

A website called Experiment caters specifically to this set. As with other crowdfunding sites, each project has a page that makes a pitch for your support. But on Experiment, consumer gadgets are replaced with research questions about amphibians, cancer cell growth and mental health. (All proposals are subject to review and approval by the site’s staff, and work involving human or animal subjects must have support from an institutional review board.)

A working paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research analyzed the platform to determine which characteristics were associated with successfully funded projects. The researchers looked at over 700 campaigns on Experiment and pulled information on the creators of the projects, from gender to prior publications to rank.

The System

What they found was striking: “experience has a negative relationship with funding success.” Not only were junior scientists more likely to successfully fund their campaigns than senior scientists, but “conventional signals of quality,” like prior publications, had no association with funding success.

“It’s different kind of projects, I think it enables people to do smaller things, or research in their very early career stages,” the paper’s lead author, Henry Sauermann, an associate professor of strategy at the European School of Management and Technology, said in an interview. His research found that the average award of a successful project was $12,617; the median was $3,103. Sauermann added that some users of the site might not even have academic affiliations, though project creators’ backgrounds run the gamut from Tier One universities to public research universities to museums.

A few researchers interviewed for this story who have run campaigns on Experiment corroborated Sauermann’s sentiments. Trevor Chapman, a PhD candidate in biological sciences at East Tennessee State University, said that he turned to the platform because grant funding was running out in his lab, and, though he’s waiting to hear back about an internal grant application, he doesn’t “have enough data or real experience to show we should be given a major NSF [National Science Foundation] grant.”

The site was launched by Cindy Wu and Denny Luan in 2012 with this kind of user in mind. As an undergraduate at the University of Washington, Wu needed $5,000 for a research project, but didn’t know where to come up with the funding. She recalled a mentor’s frank advice: “Look, Cindy, you’re 20 years old, you don’t have a PhD and the amount of money you’re looking for is too small. The system just doesn’t fund people like you.”

“Desperate Straits”

Though Experiment (originally called Microryza) was created to address this issue, Wu found the scope of the problem extended further than she initially thought, to scientists at all stages of their careers. Scrolling through projects on Experiment, scientists of every rank are represented on the pages, from undergraduate to postdoc to professor.

This might come down to a simple fact: It’s becoming harder to get research funding from traditional sources. Fiscal year 2016 marked the first time in five years that federal funding of higher education research and development increased; adjusted for inflation, the bump was a slim 1.4 percent. President Donald Trump has left the academic community on edge as he pivots between budget proposals.

“Certain political situations do affect which disciplines get funding,” Brandy Joy, a graduate student in anthropology at the University of South Carolina, said. She turned to Experiment because of financial problems in her department.

By affiliation, Sauermann found that the vast majority of creators on Experiment — 80 percent — were linked to academic institutions. Of this group, about 30 percent were undergraduate or master’s degree students, 25 percent held doctoral or medical degrees, 7 percent were postdoctoral scholars, nearly 12 percent were assistant professors, and 17 percent were associate or full professors. This means that most of the project creators on Experiment are junior scientists, though a sizeable portion hold senior ranks.

Though seniority tends to help academics in traditional grant applications, in the context of the site, junior scientists were more likely to have their projects funded successfully.

The authors consider a few explanations for this phenomenon. It’s possible, they write, that “backers consider perceived need in addition to scientific merit, or that backers derive utility from supporting the education and professional development of junior scientists.”

Sauermann said that junior scientists might also be more willing to put in the time necessary to pull off a successful campaign. His study found that projects with videos and backer updates (“lab notes”) issued prior to the close of the campaign were more likely to succeed. “This is really not necessarily a low-cost way of obtaining the funding, in the sense that it requires quite a bit of investment in engaging with the audience,” he said.

Professor Michael Pirrung agreed. Since completing his PhD in organic chemistry in 1980 he has gone on to hold a number of fellowships and is currently a distinguished professor of chemistry at University of California, Riverside. In 2013, he launched a project on Experiment to raise the $5,000 he needed to prepare a sample of an anti-kidney cancer drug his lab had developed for testing.

“I was in kind of desperate straits,” he said. He was out of funds for the project with “no prospect” of additional support. He decided to put together a campaign for Experiment, assuming that if 1,000 people contributed $5 each, he’d have the money in no time.

That’s not what happened. “I was just misinformed, naïve, whatever, about the kind of traffic that the site gets,” Pirrung said. Publicizing his project ended up being much more work than he expected. In fact, he estimated the time-spent-to-award ratio as about the same as for a formal grant application.

“Panda Bear Science”

Pirrung identified another concern with the crowdfunding platform — projects must appeal to the crowd’s tastes. “Many scientific projects are just not suitable at all for the crowdfunding model because you cannot communicate what the value or interest of the project is to the average person,” he said.

Sauermann echoed this sentiment: “There’s some concern about what’s called ‘panda bear science’ in citizen science,” he said. “Things get funded or supported that are just very appealing to the general public, but maybe they would not be interested in very basic stuff that hasn’t clarified yet what it can do later on.”

Basic research, a cornerstone of academic work, might fall by the wayside on a platform like Experiment. Indeed, Sauermann’s findings show that the crowdfunding model inverts many attributes of the traditional grant application process.

But for Wu, this concern is all but irrelevant: “I don’t think it’s the public’s job to discern what is good science and what isn’t good science. Citizens can independently fund whatever they want, and that’s a freedom that I think all citizens have.”

Three repeat funders on Experiment interviewed for this piece seemed to follow their own interests when selecting projects to fund. Jeanne Thomas, a retired dog obedience instructor, has backed four animal-related projects. Fred Hapgood, a retired science writer, has backed 14 projects. He’s interested in astronomy and animal research, too. “Most of the science funded right now is done from the point of view of what’s good for the profession,” he said. “That’s not the same as what’s the most interesting to me.”

Loren Lieberthal, a writer, has backed eight projects, mostly animal-related as well. He noted that Experiment is more “high minded” than other crowdfunding sites like Kickstarter and Indiegogo, which tend to offer incentives in exchange for pledges. “I don’t think anybody funding on Experiment is doing it because of the incentives or the perks, because there really aren’t any,” he said. Sauermann’s study found that only 11 percent of campaigns on Experiment offered rewards.

As to whether this model could present conflicts of interest, Sauermann indicated the potential for conflicts in this context actually seem lower. Most contributions on Experiment are small, so each funder has less influence. Further, funders typically are not affiliated with professional or corporate interests. Wu and Pirrung agreed that the potential for conflicts of interest was low.

It’s crowdfunding, yes, but there are different expectations on Experiment, Sauermann said. “It makes sense for a platform to say, ‘We expect our projects to be potentially successful.’” That’s a dangerous assumption for scientific projects, though.

This isn’t to say sites like Kickstarter and Indiegogo (which have orders of magnitude more users than Experiment) don’t allow a platform for academic projects. They do, and like Experiment, they get a cut of the money raised on successful projects. Experiment charges an 8 percent platform fee and the site’s payment processor charges an additional fee that amounts to between 3-5 percent of the money raised. Kickstarter and Indiegogo have similar payment processing fee schedules and each have a flat 5 percent platform fee.

Though Indiegogo does not have a specific policy addressing academic research, a spokesman for the site said such projects are allowed. The platform has hosted at least one noteworthy academic project, in which supporters of Jordan Peterson, a controversial academic and public intellectual, turned to the site to support his research after he was denied funding from traditional sources.

A number of scholarly campaigns have been funded on Kickstarter too, though the site has rules that limit the scope of projects they’ll host. Perhaps most relevant to academic work is the prohibition on “any item claiming to diagnose, cure, treat, or prevent an illness or condition.”

Further, Kickstarter requires some sort of output. The platform’s first rule: “Projects must create something to share with others.” David Gallagher, senior director of communications for Kickstarter, acknowledged that the promise of a paper might not be a compelling incentive for backers. Moreover, he said, “there’s a lot of important research that just isn’t a good fit, is maybe a little too dry to catch the internet’s attention.”

Citizen Science?

For the most part, though, it seems that funders on Experiment donate not out of their own personal academic interests but rather personal obligations. Wu estimated that on an average campaign, 70 percent of donors are people the researcher already knows, and 30 percent are strangers. Campaign creators interviewed for this article backed up this point.

Pirrung, for example, was advised by a coach on the site to tap into his social network to meet his fundraising goal, and, to some extent, he did. Pirrung said most of his backers were family members or former students. But the experience was uncomfortable: “As an academic, it’s just unseemly to me to put the arm on people I regard as friends to support my research,” he said. “And so I was just simply unwilling to do the kinds of things that some people evidently are totally fine with doing on such websites to get a project funded.”

By the end of the campaign, his goal was unmet. But Pirrung’s public relations efforts yielded a post on a blog published by Science Translational Medicine called “In the Pipeline.” The post, and the responses to it, were “somewhat circumspect,” Pirrung recalled. “Is this really the way that academic research is going to be funded in the future, where people are going to these websites, you know, kind of having bake sales for lab work?” But it attracted a donor who was willing to contribute the final $3,000 needed to meet the goal. (Pirrung worked out an agreement with the site’s staff to accept the after-the-deadline donation, and his project resulted in a publication in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.)

The skeptical reception of the project, though, reflects broader questions about the viability of the model of crowdfunding academic research.

Sauermann thinks the model is sustainable, with a caveat: “I don’t think we can expect it to replace traditional funding in terms of volume and the scope of the projects.” Projects get funded to the tune of thousands, rather than the hundreds of thousands that larger funding bodies generally offer. In fact, Sauermann found that projects with larger goals were less likely to get funded. As to volume, as of late April 2018, 787 projects had been funded through the site since its start in 2012. For comparison, the NSF funds about 11,000 proposals per year.

The jury’s also out on whether crowdfunded academic projects are succeeding in a scientific sense, Sauermann adds — a direction for future research that potentially could help address whether this system might one day exist less as a complement and more as a substitute for traditional funding bodies.

But for now, the site occupies a delicate spot. “I think it’s a viable model for funding parts of academic research,” Ethan Bucholz, a PhD candidate who used Experiment to fund his work studying forestry at Northern Arizona University, said. “I’m not so sure I would feel as confident if I were trying to fund an entire graduate stipend,” he continued, citing healthcare and living costs as expenses that perhaps exceed the capacity of the platform, if not the goodwill of its donors.

Expert Commentary