The story of the child migrant crisis at the U.S. border with Mexico has come to national attention rather suddenly, but the underlying trends and issues have a much deeper history. Among close observers of immigration patterns, these are part of a long narrative that has been building for years.

For example, in 2003, Sonia Nazario of the Los Angeles Times was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for her newspaper series “Enrique’s Journey,” which detailed the story of a young Honduran boy’s cross-border search for his mother who had migrated to the United States to look for work. A 2008 research report by the Vera Institute of Justice, “Unaccompanied Children in the United States: A Literature Review,” highlights the legal quandries with which immigration authorities and the courts have long grappled.

The current situation: Recent data

In July 2014, President Obama asked Congress for $3.7 billion to confront the “urgent humanitarian situation” unfolding at the Texas border. As gang violence and other hardships afflict Central American countries such as Honduras — which has the highest murder rate in the world — the United States has seen a record number of young migrants anxious to leave their home countries, even if they have to do so alone. This influx of “unaccompanied minors” has added a new dimension to the heated debate over immigration reform.

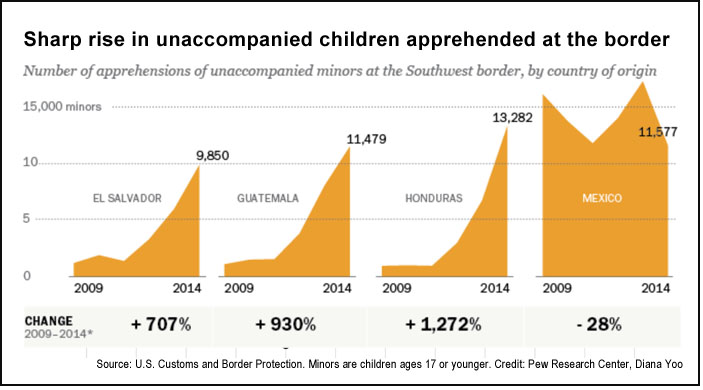

According to the Pew Hispanic Center, the number of unauthorized Latino children caught trying to enter the United States has doubled in less than a year: between Oct. 1, 2013, and May 31, 2014, 47,017 children under 18 traveling without a parent or guardian were taken into custody. That is almost twice as high as the entire previous year, which saw 24,493 such apprehensions. Three of four of these unaccompanied children came from Central America, although Mexico remains the top source of unauthorized immigrants to the U.S. overall. (For a general overview of the immigration numbers, see a July 2014 report put together at FiveThirtyEight.)

Pew also notes that children 12 and under are the fastest-growing group among this population. Taking a longer historical view, the overall increase in child migrants is dramatic: The Congressional Research Service states that “total unaccompanied child apprehensions increased from about 8,000 in [fiscal year] 2008 to 52,000 in the first eight and a half months of FY2014. Since 2012, children from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras (Central America’s ‘northern triangle’) account for almost all of this increase.”

Factors driving the trend

Why are we seeing this surge in unaccompanied minors now, particularly from Central America? One answer seems to be crime and brutal violence, which have increased throughout the region in recent years. The initial spike in child migration came between 2008 and 2009 — rising from 8,041 to 19,668 over that period — predating any recent changes in immigration policy. But some argue that the June 2012 announcement by the Department of Homeland Security of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) policy has exacerbated the problem, providing further incentive for risky journeys to cross the border, although many dispute that claim.

This political debate over root causes has been characterized by “push” and “pull” factors — the issues that drive children out of their countries, versus the incentives that attract them to migrate to the United States. The Congressional Research Service notes that this binary framing does not account for the individual experiences of child migrants, which is typically much more complicated:

The analytic dichotomy between push and pull factors often blurs in actual circumstances. For example, family reunification may occur after a parent from an origin country secures employment in the United States. Yet having an employed parent in the United States may easily make a child in an origin country more susceptible to extortion or kidnapping by criminal gangs, which in turn, may motivate the child to migrate to the United States. Hence, having an employed parent in the United States ostensibly acts as a “pull” factor while the threat of violence acts as a “push” factor, but in this example, the latter would not occur without the former. Migration to another country stems not only from macro-level circumstances such as violence and economic hardship but also personal circumstances and characteristics, such as marital status and risk tolerance. Most children have multiple motives, and how those motives influence their decisions to migrate depend on a range of factors that cannot be measured easily.

The debate also comes down to how Central Americans perceive shifts in American law and immigration policy– perceptions that may be mostly out of the control of U.S. authorities and the realities of actual law and policy. The New York Times reported in June 2014 that families in Honduras are sensing shifts in how minors are treated by U.S. authorities. Subsequent reporting by the Times, however, also notes the strong role of gang violence. But beyond anecdotal evidence, there is little reliable, representative survey data that can pinpoint these dynamics.

Perhaps the best available empirical research on root causes and migrant motivations comes from the U.N. Refugee Agency (UNHCR), which noted in its recent report “Children on the Run” that there has been a notable increase in the number of asylum seekers, including children, from El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala. The report also highlights that the number of children from these countries making the journey alone has doubled each year since 2011, and the U.S. government has estimated that 60,000 children will arrive in the U.S. in the 2014 fiscal year. While reasons for migration are often complex, interviews conducted with 404 children from El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Mexico “demonstrate unequivocally that many of these displaced children face grave danger and hardship in their countries of origin.”

Broader research on migration motives

In addition to escaping violence in their home countries, children do migrate for a variety of personal, economic and social reasons. In a 2013 paper published in the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, authors from El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, El Colegio de Mexico and the University of Pennsylvania assessed the impact of individual, household, community and other factors on adolescent immigrants from Mexico. Using data collected by the Mexican Migration Project, the authors compared variables for Mexicans who first migrated during teenage years with those who did so at later stages. Overall, they found that “determinants of migration operate differently during adolescence than later in the life course.” Some notable results include:

- Adolescents are influenced by the migration behavior in their communities and families or “migration-specific social capital characteristics” more than adults. That is, “individuals in regions with a higher prevalence of migration are more likely to take a first trip before they become adults.”

- Determinants for young migration appear to depend on gender. For females, labor market characteristics in the home community seem to be more important, especially the availability of formal jobs. In contrast, adolescent males appear to be more sensitive to changes in the destination (U.S.) labor market.

- For both males and females, staying out of the labor market can deter adolescents from migrating. “It is those who have already started their labor trajectories who are more likely to take a trip before age 19.”

For additional reports on unaccompanied minors from Central America, see sources compiled by the Women’s Refugee Council (WRC), a coalition of NGOs focused on refugee protection. Of particular relevance is an October 2012 WRC report, “Forced from Home: The Lost Boys and Girls of Central America,” which provides information based on 151 in-depth interviews with detained children. For additional information on immigration issues in general, see resources from the Immigration Policy Center, the non-partisan research and policy arm of the American Immigration Council. The organization also has a resource guide on unaccompanied children.

Damaging effects on children

There is no question that unaccompanied minors are a vulnerable population, with many becoming victims of violent crimes or sexual abuse along the journey intended to lead them away from harm. The mental strain for all migrant children is well established in the research literature: The 2011 study “Psychological Distress in Refugee Children: A Systematic Review” notes that “refugee children appear to experience high levels of psychological distress in a number of high-quality studies which employ various methods to primarily identify potential diagnoses of PTSD, depression and high levels of emotional and behavioral problems.”

A February 2014 report published jointly by the Center for Gender and Refugee Studies and Kids in Need of Defense (KIND) highlights some of these key dangers. In addition, research indicates that even those children who arrive with their families can suffer throughout the immigration process. In a 2010 paper, authors Kalina Brabeck (Rhode Island College) and Qingwen Xu (Boston College) explore the impact of detention and deportation on Latino immigrant children. Their results point to the fact that “parents in this study report their children are affected by parents’ wellbeing …. [H]ence, when undocumented Latino parents suffer as a result of detention and deportation, so too do their U.S.-born children.” The fact that deportation practices can have negative emotional, financial and academic consequences for these children has policy implications: “Individual efforts to help children of immigrants may be of limited effectiveness if the policies that threaten their families do not change…. It follows, then, that to act in the best interests of these children, policy makers and practitioners must address the emotional and financial toll that the threat of deportation exerts on immigrant parents.”

Immigration policy: The background debate

A May 2013 survey conducted by the Pew Research Center found that 75% of Americans believe immigration policy is in urgent need of an overhaul, but the country remains divided on what this reform should look like. A June 2014 Gallup poll found that “fewer than one in four Americans favor increased immigration.” The Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors Act (DREAM Act) is the legislation most directly related to immigrant minors. First introduced in 2001 by Senators Richard Durbin (D-IL) and Orrin Hatch (R-UT), the bill was meant to provide a path to citizenship for alien students brought to the United States as children. Since 2001, the DREAM Act has been re-introduced in Congress every year, either as amendments to other legislation or as an individual bill, but it has still failed to become a law.

After being unable to pass the DREAM Act, in 2012 President Obama announced the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals policy: The administration would stop deporting young, undocumented immigrants who entered the United States as children. Basically, people younger than 30 who entered the United States before the age of 16, who pose no criminal or security threat, and who were successful students or served in the military can get a two-year deferral from deportation. However, while this achieved some of the tenents of the DREAM Act, it still does not provide a path to citizenship.

Related reading: For a brief overview and history of the legislation, see the Council on Foreign Relations backgrounder on the U.S. immigration debate. In addition, a 2013 study in Perspectives on Politics explores the impact of issue frames and word choice on perceptions of immigrants.

Keywords: children, youth, Hispanic, Latino

Expert Commentary