The issue: Activist movements like Black Lives Matter have helped focus attention on police violence against unarmed black men. Camera phones allow abuses to be broadcast around the world instantly. But how does excessive police force affect black communities? New research suggests the violence undermines government authority and is even associated with a rise in crime.

An academic study worth reading: “Police Violence and Citizen Crime Reporting in the Black Community,” published in American Sociological Review, 2016.

Study summary: Matthew Desmond of Harvard University and his colleagues at Yale and Oxford build on previous studies that show black males disproportionately subject to excessive and deadly police force. They set out to determine how black communities’ relations with police are impacted by this violence.

The authors look at emergency 911 calls in Milwaukee before and after the widely publicized beating of an unarmed black man, Frank Jude, by white police officers on October 23, 2004. Calling 911 to report a crime is “foundational to public safety, being the first and among the most important acts of cooperation with the police,” they reason.

For data, they analyze every 911 call placed in Milwaukee between March 1, 2004 and December 31, 2010 — over 1.1 million calls — for location, type and duration. By looking only at calls for police help, they narrow their search to about 880,000.

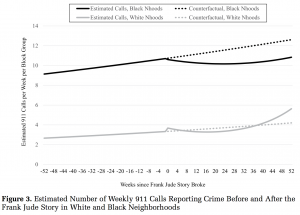

Desmond and his colleagues use an interrupted time series design, testing for changes in 911 calling patterns before and after the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel broke the story of Jude’s beating three months after it happened. They look for patterns in the 11 months before and after the beating was reported. They also test calls concerning car accidents to see if there is some other concurrent event affecting call patterns.

Finally, they also test 911 calls against three other cases of police abuse, including two murders in other states that made national news. “These two cases allow us to investigate if national reports of deadly force used against unarmed black men in other locales had any observable impact on citizen crime reporting in Milwaukee,” Desmond and colleagues write.

Findings:

- After the story of Jude’s beating broke, 911 calls for help and for violent crime both “declined significantly.” It took more than a year for crime-reporting calls to return to previous levels.

- The number of calls did not change until after the story broke.

- 911 calls declined more in African-American neighborhoods than in white neighborhoods (see table below).

- The authors estimate a net loss of approximately 22,200 calls regarding crime the year after the beating story broke; 56 percent of those were in African-American neighborhoods. By comparison, there were some 110,000 calls in that period.

- “Only people living in black neighborhoods altered their crime-reporting behavior for a significant period of time” after reports of brutality against unarmed black men.

- Patterns in calls regarding car accidents went relatively unchanged after the report of Jude’s beating, demonstrating that the “decline was specific to crime reporting.”

- This was not an isolated case. Similar patterns were apparent after the story broke in February 2007 of Danyall Simpson’s beating by a white police officer (the beating was unprovoked, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reported, but not as violent as Jude’s).

- Desmond and colleagues looked at call data before and after two national stories about unarmed black men being killed by white police officers. They found black Milwaukee residents responded in a similar way after only one of those killings — of Sean Bell in New York City in 2006.

- Fewer calls to 911 may make African-American communities less safe. In the six months after Jude’s story was published — the same months that crime reporting fell the most — murders in Milwaukee rose 32 percent compared to the same period the year before. That period was the deadliest in the seven years they surveyed, the authors observe.

- Police-community relations are difficult to repair: Even after the officers in Jude’s case were charged and fired, emergency 911 calls remained “significantly lower” in black neighborhoods.

Helpful resources:

A Washington Post database of police shootings shows that police in the United States killed 991 people in 2015. The deaths are broken down by race, gender and can be paired with other statistics.

The Marshall Project is a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization focusing exclusively on criminal justice.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics hosts data on excessive police use of force.

MappingPoliceViolence.org collects data on police killings of African Americans.

Other research:

Journalist’s Resource has profiled several studies on policing in minority communities, including research on excessive or reasonable force, perceptions of police discrimination, how body cameras affect police interactions with the public, and deaths in police custody.

A July 2016 paper by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that black men and women were more likely than white people to be beaten by police, but less likely to be shot. The study looked at racial bias after police initiated an encounter with a civilian. Some charge that it did not fully account for biases that may lead police to engage more black people in the first place.

Earlier papers have looked at cynicism within the black community — the belief that the criminal-justice system is unresponsive to their needs — and also how this cynicism does not correspond to how often someone will rely on and cooperate with the police.

Keywords: race, policing, police brutality, emergency calls, first responders, gun violence, community policing

Expert Commentary