In the United States, urban centers such as Detroit, Pittsburgh and Cleveland suffered significant job losses in the 1970s and 1980s as their manufacturing bases declined. The phenomenon wasn’t restricted to the industrial north, however — mid-Atlantic cities such as Philadelphia and Baltimore also felt the effects, as did traditional towns across the United States. What they all had in common was declining population and disinvestment in their core areas, aggravated by state and federal policies that effectively encouraged suburbanization. With infrastructure crumbling, poverty growing and social tensions rising, the cycle accelerated.

The phenomenon is often seen as being restricted to the “rustbelt,” but research indicates that similar patterns can play out within cities of all sizes, locations and ages. A 2015 study published in Applied Geography offers an analytical framework for categorizing neighborhoods in different stages: suburban, stability, blue collar, struggling and new starts. The study suggests that the transition pathways can be highly variable within rapidly growing cities such as Charlotte, N.C., and Portland, Ore., as compared to neighborhoods in cities such as Buffalo and Chicago, which see more predictable “downgrading” trajectories.

To reverse such trends, many cities have been actively working to reinvest in affected areas, encouraging mixed-use developments, new transit systems, and more. Data from the U.S. Census indicate that the majority of U.S. population growth is now in central, urbanized areas — in 2010 they held 71.2% of residents, versus 68.3% in 2000. Revitalization brings its own challenges, however, including gentrification, in which long-time, lower-income residents are displaced by newer arrivals. Boston University’s Initiative on Cities surveyed mayors across the country in 2014 and found that leaders were divided when asked to evaluate whether “it is good for a neighborhood when it experiences rising property values, even if it means that some current residents might have to move out.”

While new jobs are essential for restarting growth, the benefits aren’t always equally distributed: A 2014 study in Urban Affairs Review on 10 cities whose economies once centered around heavy industry found that economic growth in central business districts led to more income inequality. In particular, the study found that shifting from a manufacturing-based economy to education and health services led to significant growth in core areas, but also an “erosion of jobs and workforce attachment in much of the rest of the city, reflecting the uncoupling of the city’s newly emerging economy from the city’s residents.”

Such one-shot approaches — moving from one kind of economy to another — also don’t take into account the specific strengths and needs of a particular city, nor larger questions of equality, poverty and social justice. Successful, urban economic development requires careful integration of strategies across all levels, and inclusive policies on a wide array of cultural, economic and infrastructure developments and activities.

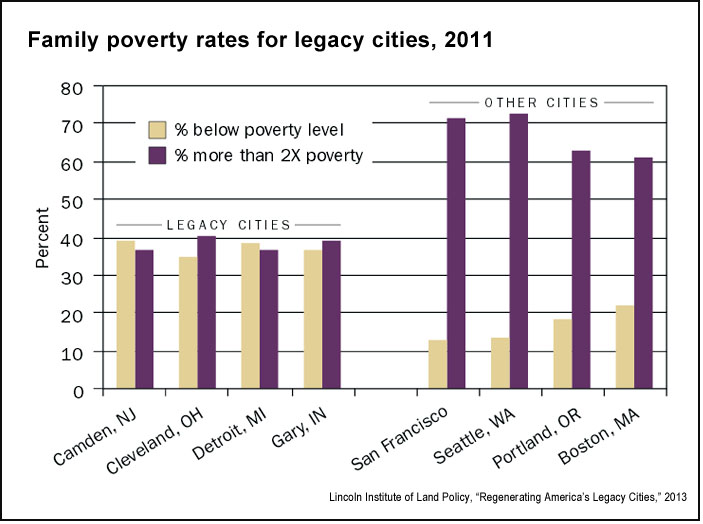

A range of recent research looks at these questions. An extensive 2013 report from the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, “Regenerating America’s Legacy Cities,” provides a deep look at 18 “legacy cities” — defined as former industrial centers that experienced decline during the second half of the 20th century. The study focuses on a sample of 18 with a population of 50,000 or more that have experienced at least 20% population loss in recent decades. The researchers, Alan Mallach and Lavea Brachman, look at 15 indicators to compare differences in these cities’ recovery efforts, before diving into what has worked for the cities that are showing strong signs of recovery — and what is not working for those still struggling with disinvestment, vacancy, population loss and economic decline.

Key findings from the report include:

- Successful city revitalization can’t be achieved by megaprojects alone — signature buildings, stadiums or other such concentrated development efforts. Instead, “it must be multifaceted and encompass improvements to the cities’ physical environments, their economic bases, and the social and economic conditions of their residents.”

- In cities that grew strongly, the economic benefits almost exclusively went to white populations, while income among African American populations grew little if at all.

- Overall economic growth is limited when low-income populations aren’t connected with new job opportunities. Consequently, social equity must be at the center of regeneration efforts: “Plans must be put in place to ensure that lower income and minority residents benefit from rising demand and economic growth.”

- Population growth among residents in the 25-34 age range is an important indicator for a city’s current economic recovery and potential for future success. This means that cities need to develop strong school systems and other public services and amenities to keep these populations in the city as they enter the 35-39 age range and start families.

- Innovative city policy can make a difference. For example, Baltimore and other cities have streamlined development efforts in what is called “vacant to value” code enforcement, as part of a broader strategy to put vacant buildings back into use.

- Flint and Cleveland are starting “land banks” with county governments to “acquire, maintain, and dispose of vacant and problem properties” in an efficient manner.

- Many struggling cities have been forced to cut staff as tax revenue decreases due to high vacancy rates; nonprofits can step in to support efforts to rebuild city capacity and staff, as happened with the Detroit Future City strategic framework funded by the Kresge Foundation.

Based on the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy report and other recent academic research, the following potential strategies emerge:

- Identify existing assets that provide a competitive advantage. For example, the presence of Johns Hopkins in Baltimore led to several millions of dollars of investment that sparked regeneration and reinvestment in that part of the city.

- Historic landmarks and cultural identity can play a key role. These could include the city’s location, its natural resources, traditional neighborhoods, and more. At the same time, a 2014 study cautions that, while preservation efforts can be important in rebuilding thriving communities, this must be undertaken in concert with broader urban policy objectives.

- Social capital is essential. A 2012 study in the Journal of Urban Affairs finds that social capital (defined as the social connections within and between community members) can be another pivotal asset to a small city. The study finds that, in cities like Scranton, Penn., a “high level of social bonding capital is a major aspect of the quality of life that small cities can offer” over larger cities.

- Link economic growth and urban well-being. Improving education, job-readiness, and access to employment opportunities among disconnected workforce members must be a key component of economic revitalization strategy in order for residents of the city to reap the benefits of job growth, and in order to fully support robust economic growth. This requires a robust regional employment strategy in order to be fully effective.

Reestablishing a coherent, cohesive central city is a crucial part of all successful revitalization efforts. Suburbanization has pulled U.S. cities apart for nearly a century, splitting them into widely distributed employment areas and residential neighborhoods connected only by highways. The counterweight to that is a fully developed, mixed-used city center with plentiful transit options for people of all interests, ages and incomes.

- Start with core residential redevelopment. An influx of new residents encourages and supports the creation of new amenities such as “supermarkets, schools, and other public and private facilities,” as in the Warehouse District in Cleveland, Washington Avenue in St. Louis or Over-the-Rhine in Cincinnati.

- Create viable neighborhoods. This is accomplished “by strengthening nonresidential cores … including nearby shopping, public schools, and other community facilities, in addition to developing transportation connections between the neighborhood, the core, and other employment centers in the city and region.”

- Repurposing disinvested areas. Through investment, vacant lots and buildings can be transformed in ways that “can enhance the quality of life” of community members.

- Develop pedestrian and bicycling infrastructure. Appealing to car-free residents and visitors has been found to have social, health and economic benefits — for example, a 2012 study from Portland State University found that they spent more at local businesses than motorists.

- City greening works. A related 2014 study on trends in “greening of urban post-industrial landscapes” finds that it can achieve an array of goals including improving the environmental sustainability and aesthetic appeal of a neighborhood, while also re-engaging the surrounding community.

- Contain sprawl. Researchers of a 2007 study find that successful containment of sprawl and suburbanization was positively associated with strong economic and physical regeneration of city centers and downtowns.

- Think regionally. Cooperation and coordination can enhance outcomes for all, including the city at the region’s core. Shared services can cut costs, while shared revenue can reduce competition for businesses between jurisdictions. Reorganizing city and county governments can also provide benefits, as shown by Indianapolis, Louisville, and Nashville.

The Lincoln Institute study concludes that American’s core cities can achieve revitalization and sustained growth with “constructive support from state and federal governments” in the form of adjusted regulations, funding programs, and other ways they can support initiatives. Revitalizing cities also requires the right mix of new forms and directions for governance and economic activity; powerful assets; and capitalizing on an “historic can-do culture of achievement.”

Keywords: economics, urban regeneration, local reporting, poverty, architecture, historic preservation, housing, research roundup

Expert Commentary