As white collar fraud has become a topic of greater media focus — and as cases from the 2007-2008 financial crisis continue to surface — one area of general consensus has been the need for more women in places of corporate leadership, in effect breaking up the “boys’ clubs” that have historically characterized Wall Street and many corporations. Of course, as some women have risen to higher positions in the corporate hierarchy, they have faced many challenges, including structural barriers such as the “glass cliff” phenomenon and generally lower compensation. But research clearly shows that having more women produces a variety of benefits for corporations. So could they help reduce fraud by networks of men? What does the past evidence indicate?

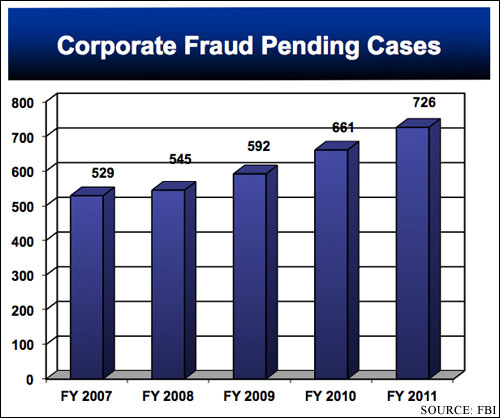

The FBI notes that most corporate fraud cases involve “accounting schemes designed to deceive investors, auditors, and analysts about the true financial condition of a corporation or business entity. Through the manipulation of financial data, the share price, or other valuation measurements of a corporation, financial performance may remain artificially inflated based on fictitious performance indicators provided to the investing public.”

A 2013 study published in the American Sociological Review, “Gender and 21st-Century Corporate Crime: Female Involvement and the Gender Gap in Enron-Era Corporate Frauds,” examines 83 representative cases of white collar fraud involving some 436 defendants, all prosecuted by the U.S. Department of Justice. The researchers, Darrell J. Steffensmeier and Michael Roche of Pennsylvania State University and Jennifer Schwartz of Washington State University, note that in the dataset analyzed are “rich details about conspiracies and offenders, including a defendant’s role in the crime, company position, extent of self-profit from a scheme, and relationships among co-defendants.” The study notes that “statistics suggest women’s opportunities to commit corporate crimes as top executives remain limited; however, their opportunities for corporate crime as mid-level managers and supervisors have markedly increased.”

A 2013 study published in the American Sociological Review, “Gender and 21st-Century Corporate Crime: Female Involvement and the Gender Gap in Enron-Era Corporate Frauds,” examines 83 representative cases of white collar fraud involving some 436 defendants, all prosecuted by the U.S. Department of Justice. The researchers, Darrell J. Steffensmeier and Michael Roche of Pennsylvania State University and Jennifer Schwartz of Washington State University, note that in the dataset analyzed are “rich details about conspiracies and offenders, including a defendant’s role in the crime, company position, extent of self-profit from a scheme, and relationships among co-defendants.” The study notes that “statistics suggest women’s opportunities to commit corporate crimes as top executives remain limited; however, their opportunities for corporate crime as mid-level managers and supervisors have markedly increased.”

The study’s findings include:

- There were “substantial gender differences” in the way crimes were perpetrated and participant profiles: “The majority of corporate offenders were male, less than one in ten was female; all solo-executed frauds were by men; no cases involved an all-female conspiracy; and all-male groups formed the preponderance of conspiracies — mixed-sex groups were only one-quarter of the total.”

- “Female conspirators profited far less than their male co-conspirators, a disparity that persisted even when controlling for corporate rank and whether one played a major role in a scheme.”

- “Women’s involvement in a company’s conspiracy came about through two main pathways: a relational pathway entailing a close personal or romantic relationship with a main co-conspirator; and a utility pathway in which a defendant occupied a strategic or gateway position in a company, such as in compliance or accounting.”

- Overall, it appears that most corporate fraud to date has a systematically exclusionary nature in terms of gender — that men, in effect, segregate themselves from women when they endeavor to commit group fraud: “Consistent with gendered opportunity structures in underworld crime networks, the same informal exclusionary practices operate among criminal co-conspirator networks in organizations.”

The researchers note a “fundamental irony” generated by their findings: “It seems a sizable portion of the indicted females in our database were unduly vulnerable to indictment and prosecution not so much because of their culpability or real contributions to the conspiracy, but instead because of their utility: they were in mid-level, easily monitored positions in which they collected and reported financial data that, in turn, made them useful tools for the prosecution to gain evidence and to turn state’s witness against co-conspirators.”

With respect to the issue of whether getting more women into higher rungs on the corporate ladder will improve the moral climate, the research findings might be interpreted two different ways, the study notes. On the one hand, “female executives might be more ethical in their decision-making, more likely to honor the fundamental laws of financial risk and avoid risk-taking excesses both within and outside the corporate setting, and less likely to create or foster a criminogenic organizational culture.” But as the researchers write, “alternatively, it is plausible that more women would not make any difference because of organizational inertia and because women who move up the corporate ladder will be socialized into the ethos of commercial interests and market dominance at all costs.”

Keywords: women and work, financial crisis

Expert Commentary