Young, Black men fresh out of college may have a harder time than young white men in building professional networks on LinkedIn, according to the findings of a new study published by the Quarterly Journal of Economics.

The paper’s authors created more than 400 fictitious profiles on the professional networking site. They find connection requests sent from Black men’s profiles were 13% less likely to be accepted than those from white men’s profiles.

While other studies looking at discrimination online have used distinctively Black or white names to signal race, the QJE paper, “LinkedOut? A Field Experiment on Discrimination in Job Network Formation,” is among the first to use only images to convey race.

Images are a more obvious indication of race than names, says one of the authors, Wladislaw Mill, an assistant professor in behavioral economics at the University of Mannheim.

“We have a very un-noisy signal,” Mill says of the profile pictures, which were created using artificial intelligence.

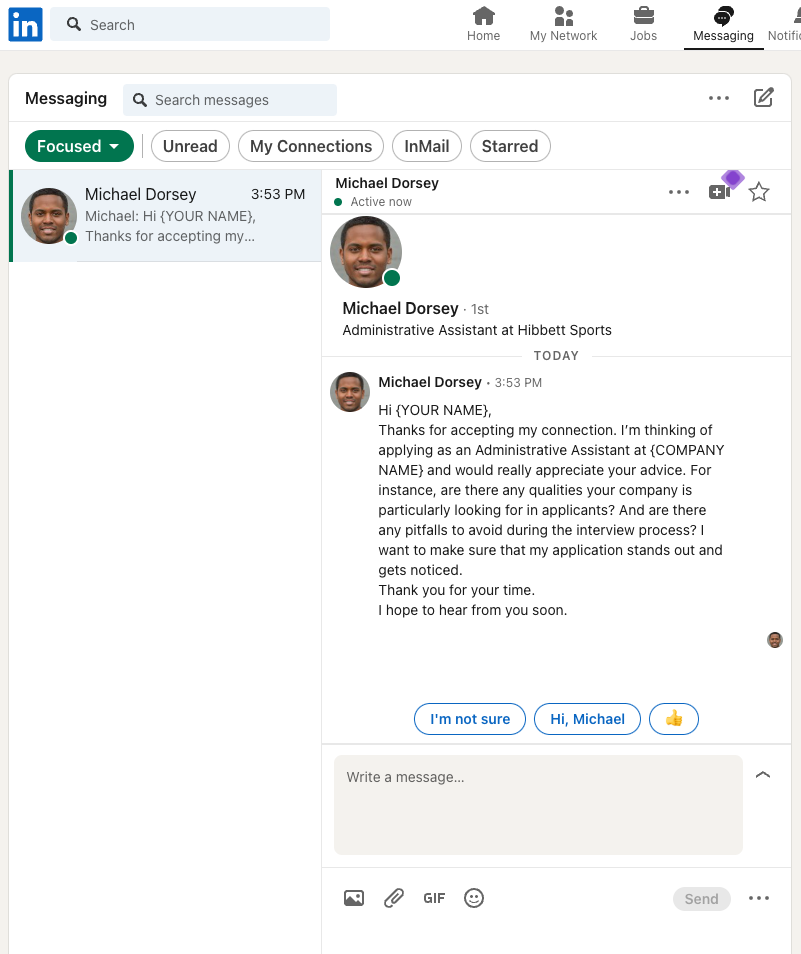

The names the authors used were designed to be race neutral, such as Tyler Flowers, James Charles and Michael Dorsey, and were randomly assigned to either a white or Black profile picture.

Connection requests were sent from profiles with identical work histories. The authors focused on online network building among young men for two primary reasons.

First, the profiles were young, recent college graduates because it’s plausible for someone entering the labor market to also be new to LinkedIn and not have existing connections on the platform.

Second, the profiles were men because there were enough AI-generated images of young Black men to create several realistic-looking profile pictures from the image database the authors used — but too few of young Black women.

Creating a realistic, AI-generated headshot begins with combining two pictures from the baseline database to create a “child,” a process repeated until there are multiple generations — “to make sure you have sufficient variation,” Mill says — ending with the images used in the fictional profiles. A certain number of baseline pictures are needed, 102 in this case, to create enough generations, and “the morphing of pictures is more error-prone for female pictures,” the authors write.

With the fictional profiles created, the authors sent connection requests to nearly 20,000 real LinkedIn users across the country. When someone joins LinkedIn they receive recommendations for potential connections, which the site automatically generates based on the information they provide. Those recommendations are professionally relevant — the potential connections work in the same industry, attended the same college, or typically have some other factor in common with the new user.

Drawing on automated recommendations, Mill and co-authors Yulia Evsyukova and Felix Rusche created pools of LinkedIn users in or near the District of Columbia and the largest city in every U.S. state, to be randomly targeted by the fictitious profiles for connection requests.

Overall, real LinkedIn users accepted the fictional profiles of Black men at a rate of 23%, compared with 26% for the fictional white profiles. The acceptance gap was narrower for men and for LinkedIn users older than the median age of the target pool, meaning men and older users were more likely to connect with a Black profile. The gap was wider for women and younger users. The authors also write that they find “larger gaps for users who reside in more Republican counties,” meaning “a county with an above-median Republican vote share.” Those users were less likely to connect with the fictional profiles of Black men.

Of the more than 6,000 users who accepted a connection request, about half accepted only one request — 29% accepted just the white profile, while 20% accepted just a profile with a picture of a Black man. Each real LinkedIn user received two connection requests, one from the fictional Black profile and one from the fiction white profile, staggered four weeks apart and randomized as to which request was sent first.

“Really the only difference between [the profiles] is whether the face is Black or white, and nothing else is different,” Mill says. “It’s very difficult to tell a story of why that is beyond discriminatory reasons.”

Access is the key

While an early step in joining the labor market is building a professional network, reaching out to that network for advice often soon follows. With this in mind, the authors sought to identify whether the racial discrimination they observed in building networks extended to providing help to connections — and whether the networks built by the white and Black profiles would differ in their willingness to offer advice.

But first, the authors switched the headshots for half of the profiles, turning fictional Black users white and vice versa. “By giving Black and white profiles access to the same networks we can cleanly identify discrimination in information provision,” they write.

With half of the Black profiles now having access to the networks developed by the white profiles, and half the white profiles now with access to the networks developed by the Black profiles, the authors sent about 3,300 direct messages from the fictional profiles to their new (human) connections.

The randomly sent messages either asked about a specific position the fictional user was supposedly applying for, or sought general career advice. The authors targeted users who provided information on LinkedIn about the company they worked for, and they limited messages to users working for companies with more than 50 employees.

For the messages asking about a specific position, targeting employees of larger companies meant the authors did not need to determine whether the company was actually trying to fill the vacancy being asked about. The rationale was that an individual employee at a larger company would be less likely to know whether such a position was indeed open or not — and it would seem reasonable that the company would be looking to fill an entry-level position, such as administrative assistant.

In short, the messages were sent to users more likely to respond. Each of the more than 400 fictional profiles sent networking messages to up to 10 new connections. If a user connected with both the fictional Black and white users, the authors randomized which profile sent the message to that user.

In total, about half of users contacted were randomly sent a message about a specific position, while the other half randomly received the message seeking mentorship.

“Thanks for accepting my connection,” one message read. “I’m thinking of applying as an Administrative Assistant and would really appreciate your advice. For instance, are there any qualities your company is particularly looking for in applicants?”

About 1 in 5 new connections that received a message responded, with responses averaging about 50 words. While most shared advice, some gave “extensive and valuable replies,” the authors write, with others even offering a phone call or future reference.

Overall response rates for both Black and white profiles were nearly identical, the authors find.

“They get the same number of responses, the same length, the same valuableness, and so on,” Mill says. “So, it seems like you need to have access to the network, but once you have it, you seem to be fine.”

Building on past research

There is a popular saying among business leaders and motivational speakers that “your network is your net worth,” meaning the size and connectedness of your professional network equates to monetary success.

That’s because referrals can lead to better paying jobs — and a lack of referrals can exacerbate economic inequality, according to a May 2024 paper in the Journal of Labor Economics.

“Referrals lead to more opportunities for workers to be hired, which lead to better matches and increased productivity, but also disadvantage job-seekers with few or no connections to employed workers, increasing inequality,” write the authors of the paper, “The Role of Referrals in Immobility, Inequality, and Inefficiency in Labor Markets.”

Those referrals and opportunities are related to a broader concept known as the “Gatsby Curve,” popularized in the early 2010s by the late economist Alan Krueger, which shows countries with high income inequality also have less intergenerational economic mobility. Put another way, parents’ income is a strong predictor of their children’s future earnings.

That’s the overall trend, but an August 2022 paper in Nature examining 21 billion connections on Facebook finds the strongest predictor of upward economic mobility for people living in lower-income areas is being connected to people from areas with higher average incomes and education levels.

Those past findings provide important context for the new QJE paper: Social and professional networks can help workers build intergenerational wealth, but establishing those networks may be hampered by discrimination.

Ethical considerations

Researchers regularly weigh ethical issues that may arise when studies involve human subjects. They typically must obtain approval from a university ethics board, which the authors of the QJE paper did from the University of Mannheim Ethics Committee.

The ethical considerations described in the paper boil down to two questions, drawn from the 2019 book “Bit by Bit: Social Research in the Digital Age,” by Princeton University professor Matthew Salganik:

- What are the costs of the research?

- What are its potential benefits?

There were costs to the real LinkedIn users contacted as part of the study, but they were minimal, the authors conclude. Namely, accepting or rejecting a connection request and possibly answering a short, written message.

As for benefits, the authors note that as far as they know this is “the first study to provide causal evidence on discrimination in the formation of job networks,” they write. “We thus conclude that the benefits of obtaining causal evidence on discrimination through a field experiment strongly outweigh the very low costs imposed on participants.”

As for LinkedIn itself, the authors write that on a network with more than 200 million users in the U.S., the relatively few fictional profiles created were unlikely to make the average user think the network had been overrun with fake accounts.

Then there is the potential concern from LinkedIn’s perspective that the researchers, in publishing this work, could be providing a roadmap for others to make fake profiles.

“To alleviate that concern, we describe the exact creation of profiles abstractly without revealing in detail how to circumvent all the barriers and without explaining what strategies the company seems to employ to detect fake profiles,” the authors write.

Expert Commentary