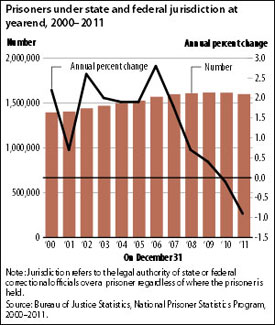

The U.S. Department of Justice has estimated the prison population under state and federal authorities at almost 1.6 million in 2011, a figure that represented a 0.9% decrease since 2010. Despite this decline, the U.S. continues to have the largest prison population in the world in both absolute and relative terms, with more than 1 in every 100 U.S. adults behind bars.

The U.S. prison population has risen significantly over time, with a 705% increase between 1973 and 2009, according to analysis by the Pew Center on the States. This was accompanied by a 305% increase in federal and state spending on prisons over two decades, totaling $52 billion annually as of 2009.

Despite the immense costs of the U.S. system, its effectiveness at rehabilitating offenders is open to question. As of 2009, 43% of released inmates were expected to return to prison (recidivism) after three years, the Pew analysis shows. Some 14% of murders are committed by individuals who are 12 months removed from prison. In an attempt to “get tough,” some states have shifted to fixed sentences rather than allowing parole boards to release prisoners early based on good behavior. Despite the political popularity of such policies, little research has been done on their impact on crime rates.

A 2013 study published in The Quarterly Journal of Economics, “How Should Inmates Be Released from Prison? An Assessment of Parole Versus Fixed Sentence Regimes,” examines the impact both parole and fixed sentencing have on released inmates’ rates.

A 2013 study published in The Quarterly Journal of Economics, “How Should Inmates Be Released from Prison? An Assessment of Parole Versus Fixed Sentence Regimes,” examines the impact both parole and fixed sentencing have on released inmates’ rates.

The author, Ilyana Kuziemko of Columbia University, analyzes data from the Georgia Department of Corrections on all inmates incarcerated in a state facility over several decades. The period included several policy discontinuities that form a “natural experiment,” allowing study of their effect on recidivism rates: First, in 1981 there was a mass release of prisoners to reduce overcrowding, with many serving less time than originally recommended. Second, in 1998 the state began requiring inmates convicted of certain crimes to complete at least 90% of their original sentence — the “90% policy” — without any possibility of an early parole.

The study’s findings include:

- Parole boards were able to accurately determine the amount of time a prisoner should face based on his or her recidivism risk: “Parole boards indeed assign longer terms to inmates with greater recidivism risk.”

- When based on risk, prison time reduces recidivism: “An extra month in prison reduces the probability that an inmate returns to prison within three years of his release by 1.3 percentage points.”

- After 1998, when Georgia required inmates convicted of certain crimes to complete at least 90% of their original sentence with no possibility of parole, affected inmates’ prison infractions and recidivism rates both increased substantially. “The results suggest that the hope of an early parole release incentivizes inmates to invest in their own rehabilitation and when such incentives are removed investment falls and recidivism rises.”

- Inmates subject to the 90% policy completed 0.13 less rehabilitative programs per year than those who had the possibility of parole. This is significant considering that the average inmate was found to complete only 0.6 such programs each year.

- The author estimates if the 90% policy were expanded to all prisoners in Georgia, the state’s inmate population would increase by 10%. In addition, there would be an increase in crime as a result of higher prisoner recidivism.

Overall, the author concludes that parole boards are able to effectively set prison time for inmates in a way that reduces recidivism. Furthermore, the study argues that very harsh policies that remove the possibility of parole for a prisoner may reduce the incentive prisoners have to invest in their own rehabilitation, and ultimately increases the recidivism rate.

A related 2011 study published in the Journal of Policy Analysis and Management finds that slightly longer prison terms are frequently associated with higher employment prospects for ex-prisoners. A 2011 Vera Institute of Justice report offers findings relating to juveniles and ways to reduce recidivism. Other research has shown the strong relationship between education for prisoners and diminished recidivism rates.

In addition, a 2012 Pew Center on the States report concludes that many nonviolent offenders could serve less time in prison, saving taxpayers’ money with few adverse societal effects: “There is a point when offenders become a low risk for release and more time served does not result in additional crimes prevented through either incapacitation or deterrence.” Finally, a 2011 study from Fordham Law School examines some of the more complex factors that have driven the increases in the U.S. prison population over time.

Tags: law, crime

Expert Commentary