Annually, the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy awards the Goldsmith Prize for Investigative Reporting to a stellar investigative report that has had a direct impact on government, politics and policy at the national, state or local levels. Six reporting teams were chosen as finalists for the 2021 prize, which carries a $10,000 award for finalists and $25,000 for the winner. Journalist’s Resource is interviewing the finalists and offering a behind-the-scenes look at the processes, tools and legwork it takes to create an important piece of investigative journalism. The article discussed here, “Think Debtors Prisons Are a Thing of the Past? Not in Mississippi,” was a collaboration between Mississippi Today and The Marshall Project, and is one of four investigations The Marshall Project submitted on “Mississippi’s Dangerous and Dysfunctional Penal System.” Joseph Neff and Alysia Santo were the other finalists from this submission, with the investigations also published in partnership with the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting, the Jackson Clarion-Ledger and the USA TODAY Network. Journalist’s Resource is a project of the Shorenstein Center, but was not involved in judging the Goldsmith Prize. The winner of the $25,000 will be announced on April 13.

Poverty reporter Anna Wolfe was new to the nonprofit Mississippi Today newsroom when she got a late-evening Facebook message from a longtime source in October 2018. The source had been trying to reach her using contact information from her old job. Wolfe and the source spoke by phone the next day while Wolfe was out on her lunch break.

Once she hung up, Wolfe hurried back to her desk to get to work following up on what she’d heard: A friend of the source named Dixie D’Angelo kept getting taken off her shifts at a local McDonald’s, and the source wasn’t sure D’Angelo was receiving care packages the source was sending to the facility where she was being held. The source wasn’t sure the Mississippi Department of Corrections was accurately recording her pay.

“That’s when I was like, ‘Wait, back up,’” Wolfe recalls. “‘There’s an inmate of the department of corrections working at McDonald’s?’ I said, ‘Maybe this isn’t a story about one person’s treatment and we need to take a look at this overall program.’”

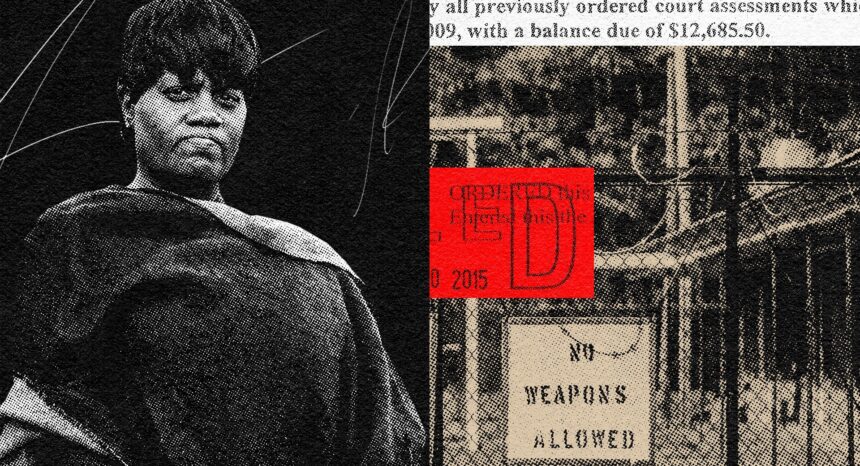

D’Angelo was indeed in state custody. A government van took her back and forth from the McDonald’s to Flowood Restitution Center, a motel-turned-jail where D’Angelo lived with dozens of other women inmates.

Wolfe says she knew she had a story when she learned D’Angelo’s sentence wasn’t based on an amount of time — it was based on an amount of money. D’Angelo had damaged a friend’s car to the tune of $5,000. She’d stay incarcerated until that debt was paid through her hourly work at McDonald’s and other restaurants. D’Angelo served nine months at Flowood while paying off the debt.

Wolfe asked Mississippi Today criminal justice reporter Michelle Liu, now a reporter with the Associated Press in South Carolina, whether she’d ever heard of an inmate working for a profitmaking corporation.

Liu hadn’t. Wolfe and Liu teamed up to pursue the story. Over the next 14 months, they interviewed 50 current and former inmates and analyzed documents from 30 public records requests to expose what they call a “modern-day debtors prison” in an article published in Mississippi Today and the nonprofit The Marshall Project, a single-subject newsroom focused on criminal justice, which contributed data analysis.

Here’s how they did it.

(Plus, read on for five investigative reporting tips.)

Building trust

The initial source gave Wolfe a baseline of credibility when she first spoke with D’Angelo. Wolfe and Liu soon approached other men and women being held at four facilities across the state while working at Church’s Chicken, Sonic Drive-In, McDonald’s and other restaurants. Some inmates worked landscaping and odd jobs at private homes. Others worked dangerous jobs, such as slaughtering chickens or gutting catfish at processing plants. Judges sentenced restitution center inmates to work off their debt following felony convictions. The program didn’t allow violent offenders.

“They didn’t usually owe a lot of money,” Wolfe and Liu write. “Half the people living in the centers had debts of less than $3,515. One owed just $656.50. Though in arrears on fines and court fees, many didn’t need to pay restitution at all — at least 20 percent of them were convicted of drug possession.”

Wolfe and Liu first approached managers to gain access to restitution center inmates at work. That was a mistake, Liu recalls. Managers weren’t willing to help the reporters gain access to their workers.

“Bosses are bosses, right?” she says. “They want their employees to be working when they’re working. They’re suspicious of outsiders. We quickly learned to approach coworkers, or we would approach folks directly and be like, ‘Hey, do you have some time? Can I come back on a work break? When does your shift end? When are you waiting for the van to come get you? Here’s our business card if you want to reach us any way that you can.’”

Tip: If your story involves reaching sources at work, think whether it makes sense to approach managers, who may not be motivated to help your reporting.

After building rapport with a few sources, trust spread to other inmates. Businesses often employed multiple restitution center inmates. Eventually, inmates would know Wolfe and Liu before they even approached them.

Many inmates Wolfe and Liu interviewed didn’t know how much they still owed — so they had little sense of how long they’d be at a restitution center. The state uses the term “resident” for inmates being held in restitution centers while working to pay off debt, although some at Flowood were there to finish traditional prison sentences. Wolfe and Liu call them inmates in their story.

No matter why they were at Flowood, inmates had basic rights taken away, even at work. They couldn’t smoke cigarettes, see friends and family or use the phone, Wolfe and Liu found. One Flowood inmate, Annita Husband, whose story serves as the main narrative thread throughout the piece, endured “strip searches for contraband at night,” they write.

Some employers knew a few of their workers were restitution center inmates, but many did not know their living conditions. One employer thought he was employing people living at a halfway house, Wolfe says.

Building a database from scratch

When Wolfe learned people were being sentenced based on an amount of money owed rather than a fixed amount of time, she knew the story needed hard numbers. Wolfe and Liu filed public records requests to obtain basic information about the restitution program. Six months into the investigation, after dozens of interviews with inmates, they started seeking public records specifically to quantify inmates’ journeys into, through and out of restitution centers.

But recordkeeping was poor. The state couldn’t easily tell Wolfe and Liu how long inmates had been in the program, or even how many people had gone through it in recent years. There was little-to-no publicly available paperwork to describe the program. Guidelines in restitution center handbooks didn’t match the experiences of inmates. Documents had been scanned and rescanned, making them difficult to read. Court sentencing orders across counties weren’t standardized, and often were incomplete. Record gathering was further slowed because records officers were almost impossible to reach.

“This is true of every agency in the state,” Wolfe says. “They will never pick up the phone.”

Tip: If you’re having trouble acquiring basic but comprehensive data on a government program, ask for a snapshot in time.

Wolfe and Liu scaled back their requests and asked for the number of inmates on a single day in a single year, and how long they’d been in the centers, to get a basic sense of the restitution program’s size.

Liu says filing public records requests shouldn’t be like playing the board game Battleship — a journalist looking for information in the public interest shouldn’t have to identify the precise records they need.

“You should be able to word something as specifically as you can but as broad as you need to, and the records officer should be able to work with you to get you what you need,” Liu says. “We started off being cordial and polite and earnest. But at the end of the day, I was filing ethics complaints against them over whether or not they had denied my requests appropriately.”

Tip: When encountering open records roadblocks, “don’t take no for an answer,” Wolfe says. “Reach out to as many different sources as possible to ask about what record you’re after, in case they know in more detail where it’s located and what it’s called.”

Wolfe and Liu tried to match court paperwork with corrections department transfer records to understand how long people were in restitution centers and whether they moved between centers. But Wolfe and Liu had never undertaken such an extensive investigative project before, let alone one that required building a database about a state institution from scratch.

They needed to refine their focus — and bolster their data — with the resources of a national outlet.

Establishing a local-national collaboration

The editor in chief of Mississippi Today at the time, R.L. Nave, reached out to an editor at The Marshall Project, Leslie Eaton, about collaborating. Nine months into the investigation, Marshall Project data reporter Andrew Calderón was assigned to help Wolfe and Liu build their dataset, with Eaton on board to help direct further reporting.

“We took a much more tailored approach after The Marshall Project came on,” Liu says. “We began thinking more critically about who our audience was and what questions we were trying to answer.”

Wolfe and Liu put aside the 15,000 or so words they’d written. Eaton pushed them to ask new questions. Did other states have restitution centers? (“A handful of states experimented with restitution programs starting in the 1970s, but abandoned them as expensive and ineffective,” Wolfe and Liu report.) What is Mississippi’s history of penal labor? (“The state has a long history of forcing prisoners — especially black men — to work,” they write.)

Calderón helped standardize the data, so it could be matched and analyzed across years. For example, when the corrections office finally provided the number of people in restitution centers by month, that data didn’t mesh with raw data the reporters had also obtained, which showed higher monthly averages.

The discrepancy was due to missing data the reporters never got. Calderón removed data on 63 inmates because it was unclear when they had entered or left a center. Still, Wolfe, Liu and Calderón tallied at least 2,343 men and women who went through the Mississippi restitution center system from 2015 to 2019.

Tip: Shoddy record keeping itself can be evidence of harm.

“With this story in particular — and I don’t think I’ve encountered it in another story I’ve worked on — the poor record keeping ended up having such dire consequences that it ended up being a really powerful piece of evidence in support of the damage that this restitution system and its dysfunctions can cause to the people who are caught in it,” Calderón says.

He used Python, a programming language, to quickly find answers to key questions, such as whether lengths of stay at restitution centers increased over time. He used Tabula to extract data from PDFs. He manually checked about 10% of the thousands of rows of data for accuracy.

Calderón relied heavily on the expertise Wolfe and Liu had developed about Mississippi’s restitution centers. They were able to answer his questions about the data, or track down answers quickly.

Tip: If you’re covering a topic you’re not an expert in, find a trusted expert to review your findings. An expert can be someone inside the system you’re investigating — for example, an inmate who can confirm whether data findings square with their personal experience.

After the investigation was published, Wolfe felt satisfied hearing from people with deep criminal justice experience in Mississippi who had been unaware the state still operated debtors prisons.

Eleven months later, a Mississippi state auditor confirmed the corrections office had mishandled hundreds of thousands of dollars in taxpayer money, and that restitution center inmates themselves suffered from financial mismanagement, with some staying in the centers after their debt was paid. One inmate remained at a restitution center despite having earned more than $1,300 above what was owed, the auditor found.

“I’m really gratified, in retrospect, that we were able to work together so well, given that I came in at the tail end,” Calderón says. “It’s a wonderful object lesson in how these collaborations can happen and how they can be really successful, and through this unity of forces you can go far beyond what you might have otherwise.”

Further reading

Covering criminal courts amid COVID-19: 6 tips for journalists

Uncovering the US prisoner transfer system and alleviating coronavirus outbreaks in prisons

Expert Commentary