Since January 20, the Trump administration has aggressively — yet quietly — expanded a controversial program that delegates immigration enforcement powers to state and local law enforcement agencies across the country that are normally prohibited from investigating and arresting non-citizens based on immigration violations.

The 287(g) program, named for the corresponding section of the Immigration and Nationality Act added in 1996, enables the Department of Homeland Security to “enter written agreement” with state and local agencies to “perform a function of an immigration officer.” 287(g) agreements are uniquely powerful for two reasons: (1) they allow U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement to quickly and dramatically expand its enforcement reach far beyond its current formal capacity, and (2) they allow non-federal agencies to overcome the longstanding prohibition against states doing their own immigration enforcement. In practice, 287(g) creates (or at least aspires to create) a direct pipeline from routine interactions with local police to detention and deportation.

Federal immigration authorities did not sign the first 287(g) until after 9/11, when the Florida Department of Law Enforcement signed one in 2002. The number of agreements grew gradually after that, then shot up at the end of the Bush administration and beginning of the Obama administration. There are three key takeaways about 287(g) from this era:

- Most — though certainly not all — of these 287(g) agreements were located in the U.S. South, in places like North Carolina and Georgia, which had seen significant relative growth in Latino residents in previous years and where I conducted much of my own research on 287(g) as a graduate student.

- Most 287(g) agreements were with county sheriffs, rather than other enforcement agencies, for two reasons. First, sheriffs are elected, which means that they had a political incentive to incorporate immigration enforcement into their campaign platforms by publicly pursuing 287(g) agreements.7 Second, sheriffs run the county jails where all law enforcement agencies in the county book people they arrest; thus, jails function as a strategic node for ICE in the larger enforcement system.

- 287(g) did not go unchallenged. The geographic expansion of immigration enforcement away from the border — what we call “interior enforcement” — was accompanied by a shift in immigrant rights organizing towards new direct and indirect anti-deportation activism (e.g., the New Sanctuary Movement), publicizing and litigating the harms caused by local anti-immigrant policies (e.g., the tragic story of Mark Lyttle), documenting concerns about the relationship between 287(g) and racial profiling, and the spread of sanctuary city policies that aimed to serve as a counterbalance to ICE’s infiltration of local jurisdictions.

In 2012, after a slew of lawsuits and investigations called attention to major problems with 287(g), specifically with the aggressive task force model, the Obama administration terminated all task force agreements, but left the jail enforcement agreements largely in place through the end of his second term.

Then Trump happened. In one of his first executive orders in 2017, President Trump instructed the Department of Homeland Security to revitalize the 287(g) program by “empower[ing] State and local law enforcement agencies across the country to perform the functions of an immigration officer in the interior of the United States to the maximum extent permitted by law” — language that Trump would use again in the executive order titled “Protecting the American People Against Invasion” issued on the first day of his second administration.

During Trump’s first administration, the number of 287(g) jail enforcement agreements doubled to about 80 — a significant expansion to be sure, but jail enforcement agreements alone did not represent a historic expansion compared to the Obama years. Instead, the Trump administration, specifically Thomas Homan, the White House executive associate director of enforcement and removal operations, as far as I can tell, invented a new 287(g) agreement to get around legal challenges that had made sheriffs nervous about getting involved in federal immigration enforcement. The Warrant Service Officer model of 287(g) more narrowly delegated to local law enforcement agencies the power to execute federal civil immigration warrants.

This alone contributed to a sudden spike in 287(g) agreements between the start of 2019 and the end of 2020, reaching over 150 active agreements at a single time and heavily concentrated in Florida but also in North Carolina, Georgia, and Texas. Unlike the early expansion of 287(g) during the Obama administration, the growth of 287(g) in 2019 and 2020 did not result in a directly observable growth in national deportations. In either case, the administration did not draw much attention to the expansion of the 287(g) program and the enormity of other immigration policies at that time, including family separation and Title 42, meant that few people outside of specific policy circles paid much attention to 287(g).

In short, between 2010 and 2020, 287(g) went from being the central controversy of national immigration enforcement policy to being largely an afterthought.

On the campaign trail, Joe Biden emphasized his distance from Trump on immigration and even promised to end the 287(g) program as part of his package of immigration policy reforms. But once in office, his administration adopted a position of equilibrium: no new agreements would be signed and, with some rare exceptions, no old agreements would be terminated. Thus, the total number and type of 287(g) agreements remained largely static, with some slight but observable attrition over four years. And like the first Trump administration, 287(g) remained largely overshadowed by border policy.

And this, friends, is where I had left it. During the pandemic, I had worked on a project with a brilliant intern, Mario Marset, to document the history of 287(g) agreements over time. But due to our respective career changes, the primacy of other immigration crises, and the demanding ongoing validation that the project required, the 287(g) paper fell just short of publication.

Joel Sati, professor of law at the University of Oregon, came to my rescue when he invited me to participate in a ‘works in progress’ conference this past weekend in Eugene. I decided that this would be the ideal opportunity to get feedback on the paper and get it published, but I was intentionally avoiding adding any new data to the paper (since this was one thing holding me back). As the conference approached, Wendy Fry, whose work for CalMatters you should definitely follow, reached out to me about a story on 287(g), prompting me to finally check ICE’s 287(g) website.

What I found was shocking.

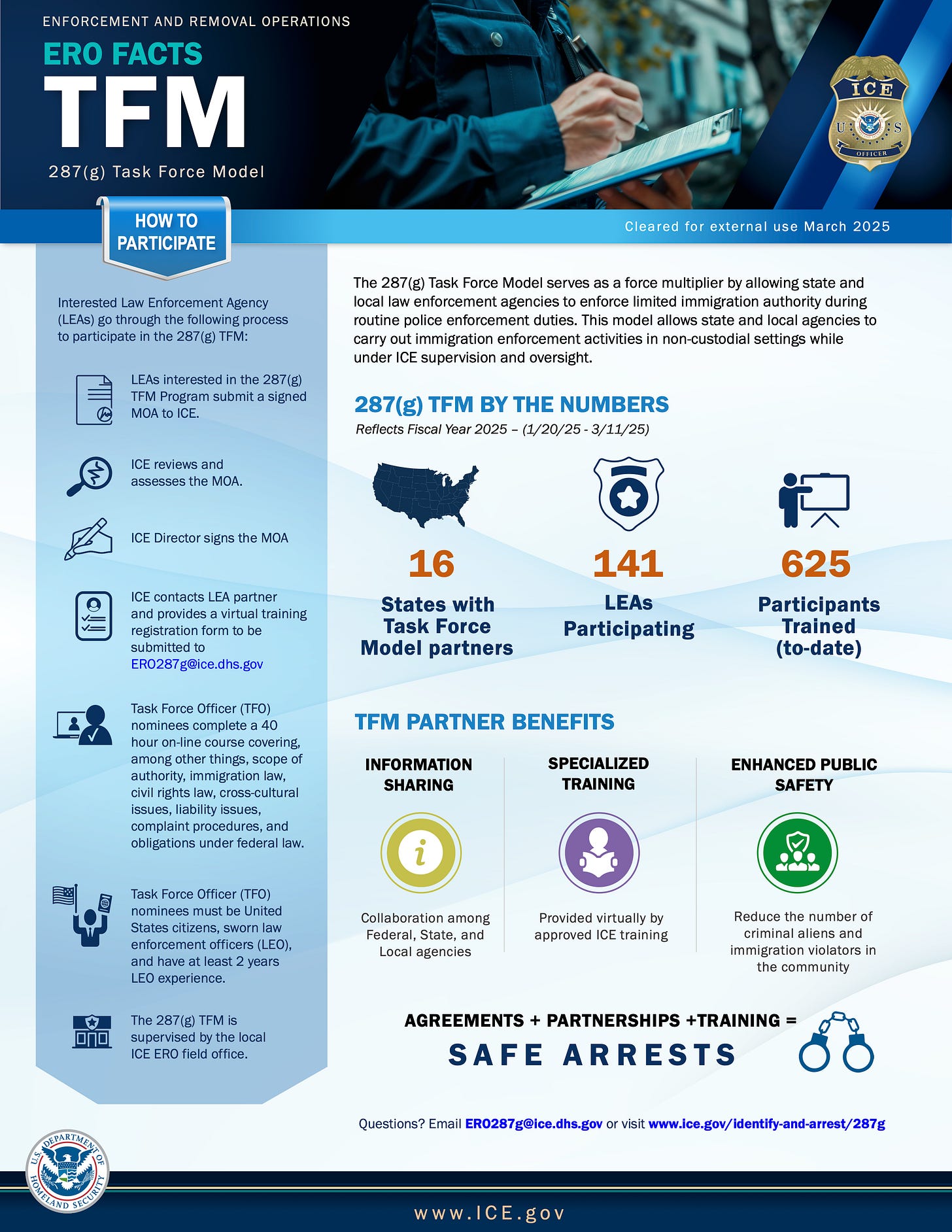

In the span of about two months, the Trump administration radically expanded the 287(g) program beyond anything I have seen in the past 15 years of close study of this precise policy. The 287(g) webpage and table of active 287(g) signatories, which hadn’t changed substantially since at least 2008, has been completely redesigned. ICE provides templated requests that local agencies can use to request a 287(g) agreement; it’s as simple as plugging in the name of the agency. ICE now provides the list of active 287(g) agreements in an Excel spreadsheet (more convenient for me, so thanks, I guess), and ICE also now provides a list of pending 287(g) agreements. ICE produced new marketing materials for the program. For example:

And there’s more. Much more. Here are three things for journalists to know as they follow this ongoing story.

1. The number of signed 287(g) agreements has exploded.

As of April 29, there are 506 active 287(g) memorandums of agreement in 38 states, according to ICE. That’s over three times the maximum number of MOAs that have ever existed. And that doesn’t count the additional 74 MOAs currently pending. When Mario and I initially did our web scraping of the data, we thought 150 287(g) MOAs was a lot, especially compared with the upwards of 80 or so that previously peaked back in 2010.

In fact, ICE signed more new 287(g) agreements in a single week of the second Trump administration (so far) than had ever existed at one time up to that point. During the week of February 24, ICE signed 140 new MOAs. In a single week.

To see 500 — and growing — is nothing short of astonishing. If it continues, which I’m sure it will, it will completely remake the landscape of interior immigration enforcement across the entire country. For now, new 287(g) agreements are heavily concentrated in Florida, Texas, North Carolina, and Georgia, but many other non-traditional states are signing on, too.

A searchable and downloadable list of all currently active 287(g) agreements is available at the end of this post.

2. The explosion of 287(g) agreements is being driven in no small part by the revival of the most criticized and concerning type of agreement: the task force model.

As of April 29, ICE had signed 231 task force model 287(g) agreements — far above the previous maximum of around 40 back in 2010. This now far exceeds the 188 active Warrant Service Officer agreements and more than the 87 active jail enforcement agreements.

Remember: The task force model effectively turns the cops you see in your community into immigration enforcement officers who can, as stated in ICE’s own marketing materials, “carry out immigration enforcement activities … during routine police enforcement duties.”

To date, across all of these new MOAs, ICE has deputized at least 625 officers specifically under the task force model.

Although we still need to understand how this authority is being used (or will be used) in practice, at least from a conceptual perspective, this means that living in 287(g) county is equivalent to the kind of policing Border Patrol conducts in communities near the U.S.-Mexico border.

3. The types of agencies signing on to 287(g) agreements have diversified wildly.

In the past, 287(g) was primarily active at the county sheriff level and, to a lesser extent, some police departments and state prisons. Now new 287(g) agreements are being signed with agencies such as the following, and I’m only including those with task force models specifically:

- Florida Department of Financial Services.

- Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

- Kansas Bureau of Investigation.

- Mississippi Attorney General’s Office.

- Montana Department of Justice.

- Oklahoma Bureau of Investigation.

- Oklahoma Bureau of Narcotics.

- Texas Office of the Attorney General.

- Florida National Guard.

- Florida State Guard.

We have never seen these types of state-level agencies get involved in 287(g) before; 287(g)s were always limited to front-line enforcement agencies or correctional institutions.

There is more to say about 287(g) and the data, and I will try to elaborate on this program in the coming days and weeks.

But we need to pull back for a minute to talk about what this means.

The staggering expansion of 287(g), and specifically the revival of the aggressive task force model, means that the Trump administration is building an army of deportation officers out of state and local law enforcement agencies at a scale that we have never seen before. Full stop.

I don’t mean that polemically or hyperbolically. I don’t even think that Thomas Homan would disagree with that framing. I think it is something that he and the administration are proud of — even though they have simultaneously been quiet about it. Bypassing constitutional restrictions on state enforcement and enrolling every law enforcement officer in the country into Trump’s mass deportation agenda is the goal. They are on their way to doing it. And no one is talking about it.

There is much left for us to understand. My previous research with Mat Coleman showed that the implementation of 287(g) can look very different in different jurisdictions. I also do not know all of the reasoning that local officials have for signing on to 287(g), nor do I understand how local policing practices are changing as a result of 287(g) — if at all.

If you are a reporter in a jurisdiction that has recently signed a 287(g) agreement, you have a unique opportunity to talk to your local law enforcement agency and elected officials about this program. The topic is massively under-reported right now. If you publish something, please share it with me so I can learn from your work.

An earlier version of this commentary first appeared on Austin Kocher’s Substack page. We’ve updated and republished it with his permission.

Expert Commentary