When companies are struggling to meet financial forecasts they are more apt to steal wages from their workers, finds recent research in the Review of Accounting Studies.

According to the paper, “Financial Misconduct and Employee Mistreatment: Evidence from Wage Theft,” when large, publicly traded firms barely meet or beat earnings forecasts they are more likely to engage in wage theft compared with years they easily beat or badly miss forecasts.

That’s after controlling for several variables that get at the costs of engaging in wage theft, including the violation rate in an industry, which picks up changes in federal enforcement practices and whether wage theft is common in an industry.

Wage theft refers to employer conduct that results in wages owed to employees going unpaid. While there is no official data on how much money American workers lose to wage theft, widely cited estimates from the nonprofit Economic Policy Institute put the yearly dollar figure in the billions, affecting at least 2 million workers. Common types of wage theft include:

- Not providing employees with their last paychecks

- Paying below minimum wage

- Not paying overtime wages

- Forcing employees to work through paid breaks

- Stealing employees’ tips

Federal law requires hourly employees be paid a minimum wage of $7.25 per hour and time-and-a-half for each hour worked above 40 hours in a week. Tipped employees make $2.13 an hour and their tips need to bring them up to the federal minimum, otherwise their employer has to cover the difference. Independent contractors and salaried employees making over $684 per week are exempt.

Overtime and minimum wage violations are among the most common forms of wage theft, says the paper’s author, Aneesh Raghunandan, an assistant professor of accounting at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

In his paper, Raghunandan analyzes instances of wage theft from 2004 to 2015 across a sample of roughly 1,800 firms. The data is from the nonprofit Good Jobs First’s Violation Tracker, a database comprised of information from federal agencies and other public sources. The average wage violation, such as paying below minimum wage, lasts 817 days — over two years — he finds.

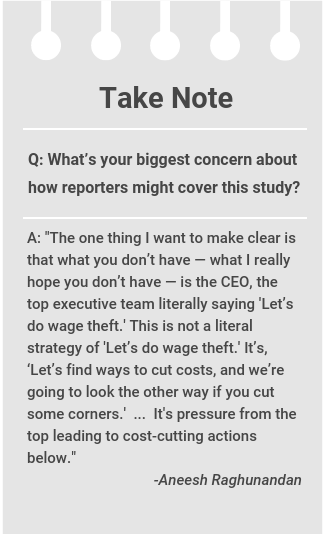

“This is not a literal strategy of, ‘Let’s do wage theft,’” Raghunandan says. “It’s, ‘Let’s find ways to cut costs, and we’re going to look the other way if you cut some corners.’”

In the wake of major corporate fraud scandals in the early 2000s, Congress passed the Sarbanes-Oxley Act in 2002, imposing stringent new accounting standards on publicly traded companies. The sample period in the study begins in 2004 because the act significantly changed the landscape of corporate accounting. The period ends in 2015 “because financial misconduct can take several years to detect and, subsequent to initial detection, class-action lawsuits can take multiple years to resolve,” Raghunandan writes.

This study takes a different approach from much of the research in recent years on corporate myopia — aiming for short-term financial benchmarks at the expense of long-term stability. Research often is framed in terms of how corporate short-sightedness affects investors, Raghunandan says.

But corporate short-sightedness “can actually hurt employees as well,” he adds. The current study provides an important tipoff on the relationship between wage theft and pressure on firms to financially perform.

Back pay and civil penalties

Since 2000, companies have paid $15 billion in federal civil penalties, settlements and court judgments related to wage and hour violations in the U.S., according to Violation Tracker data.

In one recent example, a contractor in Pennsylvania agreed on August 3 to pay back $20 million in wages stolen from 1,267 workers. The company had spread retirement money set aside for those workers across all employee retirement accounts, including those belonging to owners and executives, according to a state attorney general investigation.

A federal judge in March ordered a home health care company in Pittsburgh to make $1.6 million in back payments and damages after the U.S. Department of Labor found the company had misclassified 546 of its aides as independent contractors and owed them overtime wages.

Several household names have also reached multimillion-dollar settlements related to alleged wage and hour violations. In 2008, Walmart agreed to pay up to $640 million to settle 63 lawsuits alleging the company made employees work without pay outside of their regular hours, kept workers from taking breaks and committed other violations.

FedEx in 2016 reached a $226 million settlement of a class action lawsuit alleging the company had misclassified delivery drivers as independent contractors, denying them benefits under California law.

And in 2020, a federal judge approved $24 million in back pay for about 9,000 hourly workers at Wells Fargo who alleged the bank had not paid them overtime.

Wage violations can last years

Still, with workers losing an estimated billions of dollars yearly to wage theft, federal enforcement penalties represent a fraction of the wage theft that occurs. Federal penalties for each minimum wage and overtime violation are capped at $2,074, and employees have up to two years to recover back pay. Repeat violators attract sustained attention from federal authorities and face steeper financial penalties, Raghunandan finds. Some states also impose penalties for wage-theft violations.

“If you think about the types of workers it affects, to put it bluntly, these are workers least likely to know their rights and advocate in the workplace,” Raghunandan says. “If you and I are victims of wage theft, you may not know I’m a victim and I may not know you’re a victim, so there’s less of a perception that this is a collective problem.”

Here’s a simplified example of how wage theft might play out: A national retail outlet barely meets analysts’ earnings forecasts. Shareholders want to see better performance in the coming months. Executives direct regional managers to stop paying so much overtime, though productivity goals remain the same.

The directive trickles down to individual store managers, who now make hourly employees work through part of their lunch breaks — even in states that mandate time off for meals — without paying overtime. As weeks and months go by, the unpaid time from shorter breaks adds up to wage theft.

Companies with more employees are more likely to steal wages, a finding that “may simply reflect the fact that firms with more opportunities to engage in wage theft are more likely to do so,” Raghunandan writes.

Not only do companies that miss or barely meet earnings forecasts have a higher chance of engaging in wage theft, when regulators detect firms are stealing employees’ time and money firms tend to shift to other financial misconduct, such as executives falsely touting the capabilities of their company in public filings.

The news media’s role in deterring workplace violations

Civil penalties and court-ordered back pay can vary widely in their dollar amounts, depending on the severity of the wage theft and whether a firm is a repeat offender. Still, the possibility that a company might have to pay workers their full earnings isn’t always enough to deter wage theft.

“If the only penalty for failing to pay a worker is a court eventually ordering the employer to pay the wages due, then employers often consider wage theft a risk worth taking,” writes American University law professor Llezlie Green in an August 2019 California Law Review article.

News reports exposing wage theft may carry more deterrent heft than financial penalties alone. The Labor Department provides detailed public information on companies assessed financial penalties and ordered to pay back wages since 2005. Research indicates that public disclosure of companies that run afoul of workplace laws — and media coverage of those events — can prevent future violations.

For example, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration in 2009 began publicizing workplaces it found had committed safety violations. Press releases went to local news outlets, which began covering the violations.

One press release leads to 73% fewer violations over the next three years at similar workplaces within three miles of the cited workplace, according to a June 2020 paper in the American Economic Review. It would take the safety agency “210 additional inspections to achieve the same improvement in compliance as achieved with a single press release,” the paper finds.

Additional reading

Wage Theft in a Recession: Unemployment, Labor Violations, and Enforcement Strategies for Difficult Times

Janice Fine, Daniel Galvin, Jenn Round and Hana Shepherd. The International Journal of Comparative Labor Law and Industrial Relations, June 2021.

Structural Racism and Immigrant Health: Exploring the Association between Wage Theft, Mental Health, and Injury among Latino Day Laborers

Maria Eugenia Fernández-Esquer, et al. Ethnicity & Disease, May 2021.

Wage Theft in Lawless Courts

Llezlie Green. California Law Review, August 2019.

Regulating Wage Theft

Jennifer Lee and Annie Smith. Washington Law Review, June 2019.

How Employers Profit from Digital Wage Theft Under the [Fair Labor Standards Act]

Elizabeth Tippett. American Business Law Journal, May 2018.

Expert Commentary