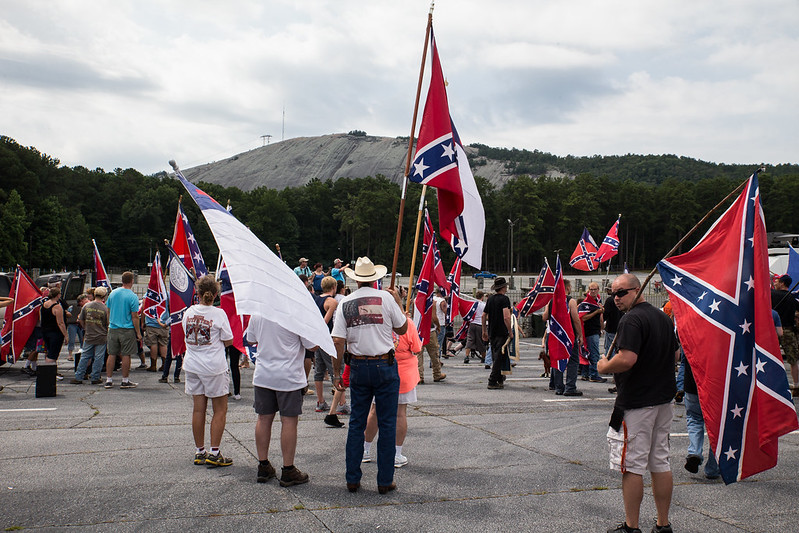

Insurrectionists who seized the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6 brandished a variety of symbols of hate as they pushed their way into the federal building to stop the certification of the 2020 presidential election. Among the most recognizable: the Confederate flag.

In response to the violent insurrection, during which a supporter of President Donald Trump carried a large Confederate flag through the Capitol, we have updated this research roundup with new studies on the flag’s enduring meanings.

Public opinion polls over the years reveal mixed opinions about the Confederate flag. A 2013 YouGov survey, for example, found that slightly more Americans see the flag as a symbol of southern pride, as opposed to a racist symbol. More recently, a national July 2020 Quinnipiac University poll shows 56% of Americans view the flag as a symbol of racism, including 55% of people living in the South.

We first published this piece after a white supremacist killed nine Black parishioners at a church in Charleston, South Carolina in June 2015. Afterward, public officials and community members successfully pushed to remove the Confederate flag from grounds near the South Carolina State House.

Violence and killings committed by white supremacists in the ensuing years spurred public debate about the appropriateness of displaying Confederate symbols, including the flag and statues of Confederate leaders, in government spaces and public parks.

What most people think of as the Confederate flag is actually the battle flag of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia — it was never an official flag of the Confederacy. Until Jan. 11, 2021, Mississippi was the last state to hoist a state flag over its Capitol that incorporated the battle emblem.

Four states — Alabama, Arkansas, Florida and Georgia — retain Confederate iconography in their flags. Meanwhile, public schools across the South remain named after leaders of the Confederacy, and students in some parts of the region are allowed to wear the battle flag on their clothes and on campus. “It is unsettled in federal courts as to whether school districts may prohibit the Confederate flag in schools,” according to an October 2020 legal analysis in the National Law Review.

A central question remains whether the flag can stand distinctly as a generalized remembrance of southern heritage, or whether it is inextricably linked to the enslavement of Black people and racist ideology.

Survey data continues to suggest that a majority of Americans consider the Civil War and slavery relevant to contemporary society. Black people still are the targets of hate crimes. And even though Jim Crow laws requiring racial segregation were removed decades ago, the health impacts of those laws persist in Black communities.

The research below provides wider historical and analytical perspective on the symbolism of the Confederate flag and ongoing debates.

—

Racial Stratification and the Confederate Flag: Comparing Four Perspectives to Explain Flag Support

Ryan Talbert and Evelyn Patterson. Race and Social Problems, March 2020.

The authors analyze data from two nationally representative surveys, one taken in 2000 and the other from 2015, with a total of roughly 7,600 participants. Their results expose stark racial stratification when it comes to support for the Confederate flag.

The authors calculate support for the Confederate flag based on a question in the 2000 survey asking whether the flag, then flying above South Carolina’s capitol, should stay or be removed. For the 2015 survey, the key question asks whether the South Carolina government made the right decision in removing the Confederate flag from statehouse grounds.

Black adults who responded to the surveys were least likely to support the flag, followed by Latinos. There was no significant difference in support or opposition among white, Asian, multiracial, Native American or Pacific Islander participants. Southerners were 64% more likely than those not from the South to support the flag.

In discussing the findings, the authors note “the flag has made its most notable appearances opposing Black advancement.” They also note the limitations of their research, including that the surveys do not capture possible changes in opinion following the Charleston church massacre. Also, the survey data could mask differences within racial groups based on whether those sub-groups identify more or less as white.

“For instance,” they write, “most Latinos have historically identified as white but do so variably by subgroup; while approximately 90% of Argentines identify as white, only about 30% of Dominicans do,” citing the 2017 book Racism Without Racists by Duke University sociologist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva.

Regional Media Framing of the Confederate Flag Debate in South Carolina

Christopher Frear, Jane O’Boyle and Sei-Hill Kim. Newspaper Research Journal, April 2019.

The authors examine the language journalists used in 400 news stories published in 2015 in three regional South Carolina newspapers about removing the Confederate flag outside the statehouse after the Charleston church massacre. Regional metropolitan news can influence public opinion more than community news, according to the authors, who aimed to determine the tone of the papers’ coverage.

They measure tone based on the amount of space given to arguments favoring or opposing removing the flag. If two-thirds of paragraphs in an article included arguments in favor of removing the flag, the authors marked the article “positive.” If two-thirds of an article focused on arguments opposing removal, the authors marked the article “negative.” All other articles were considered “neutral.”

The authors analyzed articles published from June 17 to July 12 in The Charleston Post and Courier, The State and The Greenville News. Among 173 articles in the Post and Courier, 67% were positive. Among 194 articles in The State, 64% were. And among 50 articles in the News, 38% were positive. Roughly two-thirds of articles in the News — “published in the most politically and socially conservative region of South Carolina,” the authors explain — were either negative or neutral.

“The mostly favorable tone of newspaper articles toward flag removal suggests a once-consensus symbol among white South Carolinians was now increasingly an object of repulsion,” the authors conclude. “In the context of the Charleston tragedy, corporations condemned the Statehouse flag display as did the state’s major university leaders, and national retailers including Walmart and Amazon removed from sale all products with the flag.”

Who Thinks Removing Confederate Icons Violates Free Speech?

Nathan Carrington and Logan Strother. Politics, Groups and Identities, April 2020.

People who support displaying Confederate symbols in public spaces on the basis of free speech offer an “ostensibly race-neutral justification” for keeping those symbols and monuments in place, the authors explain. In other words, supporters of Confederate symbols who rely on First Amendment arguments can claim that issues of race and racism do not play into their perspective.

“Even if it were the case that a genuine devotion to free expression was motivating these particular rights-based claims, it is still necessary to understand who is making these arguments, as well as the extent to which these arguments are motivated by race-based considerations,” the authors write.

They conducted a small, nationally representative survey of 332 voting-age Americans in June 2018 to parse motivations for support of Confederate iconography. The survey asks whether the hypothetical removal of a statue of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee would violate freedom of speech. Most respondents didn’t think so, but 14% did.

The authors note that percentage represents a small number who think removing the statue would violate free speech, and their “findings should be interpreted cautiously and will hopefully motivate future scholarship in this area.” The survey also asked about southern pride, whether Confederate icons should generally be in public places and how “warmly” participants felt toward different racial groups.

Higher levels of southern pride were correlated, but not strongly, with support for the Lee statue. Racial attitudes, however, were strongly associated with statue support. Those with a distinctly pro-white bias were three times more likely to agree that removing the Lee statue would violate freedom of speech. The authors write that their findings some individuals may use the free speech argument as a “veil used as cover for racially biased motivations in the attempt to protect racist icons.”

Pride or Prejudice? Racial Prejudice, Southern Heritage, and White Support for the Confederate FlagLogan Strother, Spencer Piston and Thomas Ogorzalek. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, June 2017.

In examining whether the Confederate flag is a symbol of “heritage or hatred,” the authors consider results from three surveys — one of Georgians in 2004, another of South Carolinians in 2014 and a 2008 nationally representative panel survey. They also consider historical evidence of the flag reemerging in the Deep South as a political and racist symbol during 1950s and 1960s civil rights movements.

“While our findings yield strong support for the hypothesis that prejudice against Blacks bolsters white support for Southern symbols, support for the Southern heritage hypothesis is decidedly mixed,” they find. “Despite widespread denials that Southern symbols reflect racism, racial prejudice is strongly associated with support for such symbols.”

Heritage or Hatred: The Confederate Battle Flag and Current Race Relations in the U.S.A.

Scott Moeschberger. Symbols that Bind, Symbols that Divide, Peace Psychology Book Series, April 2014.

With merchandise featuring Confederate iconography for sale across the country, the author ponders whether the “symbolism of the Confederate flag seems to overstep the simple association with the geography of the civil war.”

“Why do so many individuals use the Confederate flag as a symbol?” he asks. “Is it a statement supporting the cause of Southern slave owners and the oppression of blacks or an indication of some kind of solidarity with states’ rights and the desire for independence from the federal government?”

The author doesn’t offer firm answers, but food for thought: “So how does this powerful symbol relate to issues of peace building and reconciliation within society? Society must continue to engage the contradictory and dynamic meanings that the flag embodies. It is a central part of the American story — of rebellion, Southern pride, and slavery.”

Other People’s Racism: Race, Rednecks and Riots in a Southern High School

Jessica Halliday Hardie and Karolyn Tyson. Sociology of Education, January 2013.

A racial confrontation broke out in February 2007 after a white student used a racial slur and while the authors were conducting other research at a North Carolina school, bringing into “stark relief the unfinished business of racial reconciliation in the South,” they write.

“The southern United States is an important region in which to study race relations among youth and school racial conflict,” the authors explain. “Racial confrontations occur regularly in schools across the country, but the one that occurred in North Carolina involved symbols of racism and racial violence and intimidation tied to the Old South.”

Drawing on nine months of field interviews, including after the North Carolina confrontation and similar events, the authors conclude their research is an “important reminder of the continuing salience of race in everyday life, especially in schools.”

Black, White or Green? The Confederate Battle Emblem and the 2001 Mississippi State Flag Referendum

Gerald Webster and Jonathan Leib. Southeastern Geographer, fall 2012.

Debates about displaying the Confederate flag in public have occurred since the late 1980s “with attitudes in these debates largely divided along racial lines,” the authors write. They examine public arguments made in April 2001 about a public referendum to change the Mississippi state flag, which featured the battle emblem.

“In the end, voters in Mississippi overwhelmingly approved retaining the Confederate battle emblem within the design of their state flag,” the authors write. “However, based on events elsewhere in the region, we believe the flag debate will continue in Mississippi.”

How Exposure to the Confederate Flag Affects Willingness to Vote for Barack Obama

Joyce Ehrlinger, et. al. David A. Butz. Political Psychology, November 2010.

“Leading up to the 2008 U.S. election, pundits wondered whether whites, particularly in Southern states, were ready to vote for a Black president,” write the authors, who examined how Confederate images affect the likelihood of study subjects’ willingness to vote for America’s first Black president.

In one study of 130 college students at a large state school in the South, most of them white and about one-fifth of them Black, the authors find that participants quickly shown an image of the Confederate flag were less willing to vote for Obama compared with those who were shown a “neutral symbol made up of colored lines.”

A second study of 116 white students reveals that students who saw an image of the flag before reading a story about a fictional Black man had a more negative reaction to the story than did students who did not see the flag before reading the story.

The authors conclude that “the prevalence of this flag in the South may have contributed to a reticence for some to vote for Obama because of his race.”

Race Discourse and the U.S. Confederate Flag

Lori Holyfield, Matthew Ryan Moltz and Mindy Bradley. Race, Ethnicity and Education, November 2009.

The authors explore how racial hierarchies persist through findings from focus groups held in 2006 with 350 students at a predominately white university in the South.

“While our study cannot be generalized to the larger population, we found using the Confederate flag to solicit discussions of race a helpful strategy to further examine the social construction of whiteness in the American south,” the authors conclude. “As with previous findings, this group of white college students appeared to have difficulty examining their own racial identity, raising concerns that perceived racial transparency continues to prohibit race consciousness.”

Region, Race and Support for the South Carolina Confederate Flag

Christopher Cooper and H. Gibbs Knotts. Social Science Quarterly, March 2006.

The authors conducted a nationally representative phone survey with 5,544 adults to better understand how Americans’ attitudes about the Confederate flag are affected by the regions where they live.

“Although racial attitudes are important among both southerners and non-southerners, region and race also influence support for the Confederate flag,” they write. “Southern whites have the greatest support for the flag followed by non-southern whites, non-southern blacks, and southern blacks. Support for the Confederate flag is not simply about racial attitudes, but a more complex phenomenon where region and race exert important influences.”

Long Ago and Far Away: How U.S. Newspapers Construct Racial Oppression

Hemant Shah and Seungahn Nah. Journalism, August 2004.

This paper offers an historical snapshot of reporting about race, mostly drawing on journalism from the 1990s. The authors examine 146 news articles from 1990 to 2001 that prominently use the phrase “racial oppression” to explore how racial oppression unfolds and who is involved.

They find that “the U.S. press constructed racial oppression in fairly narrow ways,” with “stories focused on apartheid, slavery and the confederate flag” depicting racial oppression as “involving almost exclusively Blacks and whites.”

Political Culture, Religion and the Confederate Battle Flag Debate in Alabama

Gerald Webster and Jonathan Leib. Journal of Cultural Geography, fall/winter 2002.

The authors analyze the debate around and results of a 1999 nonbinding vote by members of the Alabama House of Representative on whether to continue displaying the Confederate flag in their chambers. The measure passed 50- 38 in support of removing the flag. But subsequent efforts in 1999 and 2000 failed to bring a binding resolution.

The authors write that “both political culture and religion aid in an understanding of the passionate condemnations and defenses of the Confederate Battle Flag,” and further offer that “both sides in these debates believe God and morality is on their side, and political compromise is therefore viewed as amoral if not immoral.”

The South Carolina Confederate Flag: The Politics of Race and Citizenship

Laura Woliver, Angela Ledford and Chris Dolan. Politics & Policy, December 2001.

Based on their observations at five public rallies, along with 17 interviews with activists, legislators and community leaders representing both sides of a debate on whether to keep the Confederate flag flying atop the South Carolina Capitol, the authors seek to “explain how the effort to remove the Confederate flag was partially successful.”

They find that “extensive preliminary work prepared the terrain for the mobilizing effects of several galvanizing events,” including an NAACP tourism boycott in the state and national media attention, “which pressured institutions-parties, the legislature, the governor — to respond.”

The flag was ultimately removed in 2000 from the Capitol and placed at a monument in front of the Capitol. Later, after the 2015 Charleston church massacre, it was moved to a museum for Confederate relics.

Whose South Is It Anyway? Race and the Confederate Battle Flag in South Carolina

Gerald Webster and Jonathan Leib. Political Geography, March 2001.

The authors analyze a binding South Carolina legislative vote from 1997 on whether the state should hold a voter referendum on whether to continue flying the Confederate flag atop the state Capitol.

“Given that most white voters supported the battle flag remaining atop the Capitol dome, pro-flag legislators were likely to be confident that such a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ referendum would ‘democratically’ confirm their positions,” the authors write.

Researchers also examined legislative support for putting the Confederate flag on specialty license plates. Both measures — on whether to allow the battle emblem on license plates and whether to hold a referendum — passed easily.

“These debates are centrally about power, and whose collective vision or agenda will be carried out,” the authors write. “The Confederate battle flag controversy degrades into shrill debate because southern whites see themselves as distinct, under siege by attacks on their symbols, and their point of view as culturally and morally centrist.”

Expert Commentary