On February 11, 2015, President Obama made a formal proposal to Congress seeking an authorization for the use of military force (AUMF) for three years against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (abbreviated as ISIL or ISIS). Should the House and Senate approve this measure, it would be the first time since 2002 — when lawmakers permitted the use of force against Saddam Hussein’s Iraq — that Congress has formally signed off on a new military authorization.

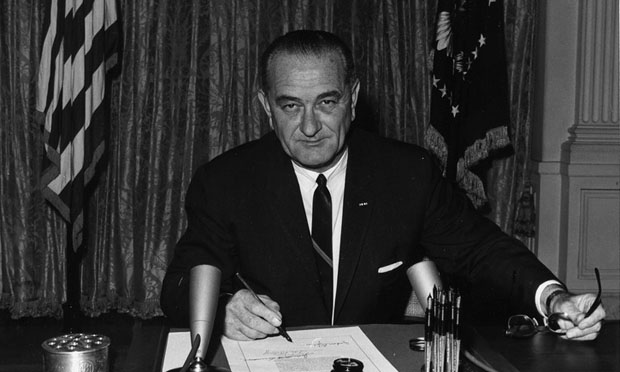

Other precedents in recent American history include the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in 1964, during the Vietnam War under President Johnson; the Gulf War resolution in 1991 under President George H.W. Bush; and the authorization for the use of force in the immediate aftermath of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, under President George W. Bush. At issue for President Obama and Congress is also what to do with the 9/11 and Iraq War resolutions, neither of which have been terminated. (In the case of the Gulf of Tonkin/Vietnam resolution, the measure was ultimately repealed by Congress seven years later, in 1971.)

The issues of the proper separation of powers and their respective responsibilities for authorizing combat remain unresolved in the American system, as the U.S. Constitution itself specifies in somewhat contradictory fashion that while Congress has the power to declare war, the president alone is the commander-in-chief. In general, American presidents seek such approvals from Congress only when they anticipate a conflict of long duration (the invasions of Grenada in 1983 and Panama in 1989, for example, as well as the bombing of Serbia and intervention in Kosovo in 1999, saw no such Congressional authorizations.)

In 1973, Congress passed the War Powers Act, following years of tension with Presidents Johnson and Nixon, whose representations to Congress about Vietnam turned out to be falsely optimistic. The War Powers Act requires, among other things, that the president notify Congress of the reason for committing combat troops within 48 hours of their deployment, and it specifies that hostilities must end within 60 days unless Congress extends that period. Presidents have traditionally claimed that this resolution infringes on their constitutional powers.

Based on the historical record and patterns of public opinion, political scientists generally conclude that, even if presidents gain in the short run by acting on their own, they undermine their capacity to lead in the long run if they fail to keep in mind that Congress is a coequal branch of government. Scholars and policymakers have long debated these balance-of-power issues with respect to military force. The following papers and reports provide insights into a variety of salient issues:

_______

“National War Powers Commission Report”

James A. Baker III; Warren Christopher; et al. Miller Center for Public Affairs, University of Virginia, 2008.

Excerpt: “No clear mechanism or requirement exists today for the President and Congress to consult. The War Powers Resolution of 1973 contains only vague consultation requirements. Instead, it relies on reporting requirements that, if triggered, begin the clock running for Congress to approve the particular armed conflict. By the terms of the 1973 Resolution, however, Congress need not act to disapprove the conflict; the cessation of all hostilities is required in 60 to 90 days merely if Congress fails to act. Many have criticized this aspect of the Resolution as unwise and unconstitutional, and no President in the past 35 years has filed a report ‘pursuant’ to these triggering provisions. This is not healthy. It does not promote the rule of law. It does not send the right message to our troops or to the public. And it does not encourage dialogue or cooperation between the two branches.”

“Syria, Threats of Force and Constitutional War Powers”

Matthew C. Waxman. Yale Law Journal Online, 2013, 123:297.

Excerpt: “The recent Syria case has inspired much discussion about constitutional war powers and much discussion about the credibility of threats. Those two conversations should be combined because the issues are tightly linked. Lawyers think ‘war powers’ are about making war or conducting military operations. They therefore examine wars and military operations to describe how war powers are exercised, and they often defend various interpretations of these powers with functional arguments about how best to wage war or conduct military operations. Focusing on decisions to use force — the actual engagement of military operations in armed violence — and formal legal constraints on them misses the many decision points that lead up to them. War powers decisions — in a practical sense, not a formal sense — occur earlier along the foreign policy decision tree than is generally acknowledged or understood in legal debates. Because the United States is a superpower that plays a major role in sustaining global security, its ability to threaten war is in some respects a much more policy-significant constitutional power than its power to actually make war. Despite the intense emphasis on it in discussions of foreign policy, knowledge of how states acquire, maintain, or lose credibility to use force remains severely limited. In thinking about the future of American constitutional war powers, legal scholars need to update their thinking about the strategic virtues of deliberative checks versus presidential flexibility to better account for what is known and is not known about these phenomena.”

“Congressional Authorization and the War on Terrorism”

Curtis L. Bradley; Jack L. Goldsmith. Harvard Law Review, May 2005, Vol. 118, No. 7.

Excerpt: “This Article presents a framework for interpreting Congress’s September 18, 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF), the central statutory enactment related to the war on terrorism. Although both constitutional theory and constitutional practice suggest that the validity of presidential wartime actions depends to a significant degree on their relationship to congressional authorization, the meaning and implications of the AUMF have received little attention in the academic debates over the war on terrorism. The framework presented in this Article builds on the analysis in the Supreme Court’s plurality opinion in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, which devoted significant attention to the AUME. Under that framework, the meaning of the AUMF is determined in the first instance by its text, as informed by a comparison with authorizations of force in prior wars, including declared wars. In ascertaining the scope of the ‘necessary and appropriate force’ that Congress authorized in the AUMF, courts should look to two additional interpretive factors: Executive Branch practice during prior wars, and the international laws of war. Although nondelegation concerns should not play a significant role in interpreting the AUMF, a clear statement requirement is appropriate when the President takes actions under the AUMF that restrict the liberty of non-combatants in the United States. The authors apply this framework to three specific issues in the war on terrorism: the identification of the enemy, the detention of persons captured in the United States, and the validity of using military commissions to try alleged terrorists.”

“Limited War and the Constitution: Iraq and the Crisis of Presidential Legality”

Bruce Ackerman; Oona Hathaway. Michigan Law Review, February 2011, Vol. 109, No. 4, 447-517.

Excerpt: “The presidency is not solely responsible for this unconstitutional escalation. Congress has failed to check this abuse because it has failed to adapt its central power over the use of military force — the power of the purse — to the distinctive problem of limited war. Our proposal restores Congress to its rightful role in our system of checks and balances. We suggest that the House and Senate adopt new ‘Rules for Limited War’ that would create a presumption that any authorization of military force will expire after two years, unless Congress specifies a different deadline. The congressional time limit would be enforced by a prohibition on future war appropriations after the deadline, except for money necessary to [end] the mission. These new rules would not only prevent presidents from transforming limited wars into open-ended conflicts; they would also create incentives for more robust democratic debate. Under the Constitution, either the House or the Senate may adopt these rules unilaterally, thereby avoiding the threat of presidential veto. Building on this constitutional foundation our proposal provides a practical way in which Congress may effectively reassert its constitutional power — and with it more effective democratic control — over the use of military force.”

“Military Operations in Libya: No War? No Hostilities?”

Louis Fisher. Presidential Studies Quarterly, March 2012, Vol. 42, No. 1. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-5705.2012.03947.x.

Excerpt: “The Obama administration produced two remarkable legal opinions about the use of military force against Libya. A memo by the Office of Legal Counsel reasoned that the operations did not amount to ‘war.’ Later, after military actions exceeded the 90-day limit of the War Powers Resolution (WPR), President Obama was advised by White House Counsel Robert Bauer and State Department Legal Advisor Harold Koh that the operations did not even constitute ‘hostilities’ within the meaning of the WPR. This article examines those interpretations and other legal arguments by the executive branch, including the claim that the military actions in Libya had been ‘authorized’ by the UN Security Council and North Atlantic Treaty Organization allies.”

“Ending Perpetual War? Constitutional War Termination Powers and the Conflict Against Al Qaeda”

David A. Simon. Pepperdine Law Review, April 2014, Vol. 41, Issue 4.

Excerpt: “This Article presents a framework for interpreting the constitutional war termination powers of Congress and the President and applies this framework to questions involving how and when the war against Al Qaeda and associated forces could end. Although constitutional theory and practice suggest the validity of congressional actions to initiate war, the issue of Congress’s constitutional role in ending war has received little attention in scholarly debates. Theoretically, this Article contends that terminating war without meaningful cooperation between the President and Congress generates tension with the principle of the separation of powers underpinning the U.S. constitutional system, with the Framers’ division of the treaty-making authority, and with the values they enshrine. Practically, this Article suggests that although the participation of both Congress and the President in the war termination process may make it more difficult to end a war, such cooperative political branch action ensures greater transparency and accountability in this constitutional process.”

“Demise of the War Clause”

David Mervin. Presidential Studies Quarterly, December 2000, Vol. 30, No. 4, 770-776. doi/10.1111/j.0360-4918.2000.00143.x.

Excerpt: “On both democratic and prudential grounds, it is essential that presidents work with Congress on such occasions. What is being questioned here is whether Congress should have the last word, as the framers undoubtedly intended. In the same way that some other features of the Constitution have become anachronisms, literal readings of the War Clause are not supportable in the modern age, and we cannot ignore the limitations of the framers’ mindset touched on earlier. Congressional preeminence in war making, like Thomas Jefferson’s warning against the dangers of ‘entangling alliances,’ made sense at the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century, but neither are relevant to international politics two hundred years later. And however difficult it is to stomach, the president’s information advantage vis-à-vis Congress in the modern era cannot reasonably be denied even if that superiority is categorically no guarantee of good policy.”

“Virtues of the War Clause”

David Gray Adler. Presidential Studies Quarterly, December 2000, Vol. 30, No. 4, 777-782. doi: 10.1111/j.0360-4918.2000.00144.x.

Excerpt: “Congress, alone, possesses the war power, just as Congress, alone, possesses the spending power. A congressional unwillingness to exercise either of its powers does not justify presidential usurpation on any ground, and certainly not on grounds of changing circumstances, superior information, or congressional incoherence. The grant of power to one branch precludes its exercise by another. If a president strongly, even fervently, believes military force is necessary, he is allowed to argue his case before Congress. But he may go no further if constitutional government is to command any respect.”

Keywords: terrorism, war powers, Vietnam, war on terror, Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, research roundup, presidency, war

Expert Commentary