The controversy over NFL star Ray Rice and the instance of domestic violence he perpetrated, which was caught on video camera, stirred wide discussion about sports culture, domestic violence and even the psychology of victims and their complex responses to abuse. In 2015, domestic violence drew a national spotlight again when the South Carolina newspaper, the Post and Courier, won a Pulitzer Prize for its investigation of women who were abused by men and had been dying at a rate of one every 12 days.

The research on domestic violence, referred to more precisely in academic literature as “intimate partner violence” (IPV), has grown substantially over the past few decades. Although knowledge of the problem and its scope have deepened, the issue remains a major health and social problem afflicting women. In November 2014 the World Health Organization estimated that 35% of all women have experienced either intimate partner violence or sexual violence by a non-partner during their lifetimes. This figure is supported by the findings of a 2013 peer-reviewed metastudy — the most rigorous form of research analysis — published in the leading academic journal Science. That metastudy found that “in 2010, 30.0% [95% confidence interval (CI) 27.8 to 32.2%] of women aged 15 and over have experienced, during their lifetime, physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence.” The prevalence found among high-income regions in North America was 21.3%. Of course, under-reporting remains a substantial problem in this research area.

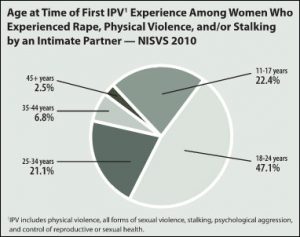

In 2010, the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, conducted by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, found that “more than 1 in 3 women (35.6%) … in the United States have experienced rape, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime.” That survey was subsequently updated in September 2014. The findings, based on telephone surveys with more than 12,000 people in 2011, include:

The lifetime prevalence of physical violence by an intimate partner was an estimated 31.5% among women and in the 12 months before taking the survey, an estimated 4.0% of women experienced some form of physical violence by an intimate partner. An estimated 22.3% of women experienced at least one act of severe physical violence by an intimate partner during their lifetimes. With respect to individual severe physical violence behaviors, being slammed against something was experienced by an estimated 15.4% of women, and being hit with a fist or something hard was experienced by 13.2% of women. In the 12 months before taking the survey, an estimated 2.3% of women experienced at least one form of severe physical violence by an intimate partner.

Still, the overall rates of IPV in the United States have been generally falling over the past two decades, and in 2013 the federal government reauthorized an enhanced Violence Against Women Act, adding further legal protections and broadening the groups covered to include LGBT persons and Native American women. (For research on the relatively higher violence rates among gay men, see the 2012 study “Intimate Partner Violence and Social Pressure among Gay Men in Six Countries.”)

In terms of victim response, social scientists continue to examine factors that might predict when women may feel empowered to report abuse and leave relationships.

In terms of victim response, social scientists continue to examine factors that might predict when women may feel empowered to report abuse and leave relationships.

A 2013 study published in the Journal of Marriage and Family, “Women’s Education, Marital Violence, and Divorce: A Social Exchange Perspective,” analyzes a nationally representative sample of more than 900 young U.S. women to look at factors that make females more likely to leave abusive relationships. The researchers, Derek A. Kreager, Richard B. Felson, Cody Warner and Marin R. Wenger, are all at Pennsylvania State University. They note that traditional “social exchange theory” would suggest that as women have more resources, they become less dependent on men and have more opportunities outside relationships, and therefore have more ability to divorce. The study sets out to “determine whether the relationship between a woman’s education and divorce is different in violent marriages.” The researchers also hypothesize that women who have higher levels of education are less likely to get divorced in general — prior academic work they cite supports this — but they aim to see how the introduction of intimate partner violence changes this dynamic.

The study’s findings include:

- The data provide “support for our primary hypotheses that women’s education typically protects against divorce but that this association weakens in abusive marriages. In addition, we found a similar pattern for wives’ proportional income, net of education. Together, these patterns suggest that educational and financial resources benefit women by increasing marital stability in nonabusive marriages and promoting divorce in abusive marriages.”

- Further, the “greater tendency for educated women to leave abusive marriages was substantial. For example, in highly violent marriages, women with a college degree had over a 10% greater probability of divorce in the observed time period than women without a college degree.”

- The study also finds that “women with economic resources were likely to leave unhappy marriages, regardless of whether they involve abuse. Similarly, degree-earning women were more likely than less educated women to leave violent marriages, regardless of their feelings of dissatisfaction.”

The researchers note that, across the U.S. population, more women are attaining college degrees, and given the study’s findings, this suggests “increases in women’s education should reduce rates of domestic violence. In a population with many educated women, violent marriages are likely to break up.” They caution that it is also possible “that our observed patterns reflect husbands’ perceptions and decisions. Perhaps abusive men feel threatened by successful wives, which then increases divorce risk. Nonabusive men may not feel threatened and thus stay with successful women.” On this point, more research is required.

Related research: A 2015 study titled “When War Comes Home: The Effect of Combat Service on Domestic Violence” suggests that multiple deployments and longer deployment lengths may increase the chance of family violence. A June 2014 study published in the Journal of Interpersonal Violence, “Intimate Partner Violence Before and During Pregnancy: Related Demographic and Psychosocial Factors and Postpartum Depressive Symptoms Among Mexican American Women,” provides a snapshot of domestic violence in a community sample of low-income Hispanic women. A March 2013 report from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Female Victims of Sexual Violence, 1994-2010,” provides a broad picture of such crimes across American society, examining the demographics of both victims and offenders. Regarding the issue of IPV prevention, a 2003 metastudy published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), “Interventions for Violence Against Women: Scientific Review,” found that “information about evidence-based approaches in the primary care setting for preventing IPV is seriously lacking…. Specifically, the effectiveness of routine primary care screening remains unclear, since screening studies have not evaluated outcomes beyond the ability of the screening test to identify abused women. Similarly, specific treatment interventions for women exposed to violence, including women’s shelters, have not been adequately evaluated.” Subsequent research continues to find problems with current techniques for screening and detection.

Tags: gender, women and work, crime, sex crimes

Expert Commentary