The issue: Since penicillin was introduced in the 1940s, antibiotics have saved countless lives. But we have used these drugs so much for so long that the diseases they once killed have adapted and developed immunity. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 23,000 Americans now die each year from infections by bacteria that are impervious to antibiotics.

The misuse and excessive use of antibiotics to treat benign and common illnesses and to boost productivity in farming has contributed to their waning potency. The CDC estimates antibiotics are improperly prescribed 50 percent of the time. In some countries you do not even need a prescription, but can simply purchase them over the counter. Overuse has allowed bacteria, viruses, parasites, and fungi to mutate and build immunity. (Antibiotics are a type of antimicrobial, which is, broadly speaking, a drug designed to kill or treat infections.) “Antimicrobial resistance” (AMR) is a man-made problem.

Researchers fear that these newly immune pathogens — sometimes called “superbugs” — are as dangerous as any pandemic because, even though they are familiar, there is no cure. And because untreatable bacteria lurk in hospitals, they make routine procedures like dental surgery far more dangerous. The 20th century’s gains in longevity are at risk.

Drug-resistant diseases do not respect borders, making this a global problem requiring global cooperation and standards on the use of antibiotics, a new World Bank paper says.

An academic study worth reading: “Drug-Resistant Infections: A Threat to Our Economic Future,” by the World Bank, 2016.

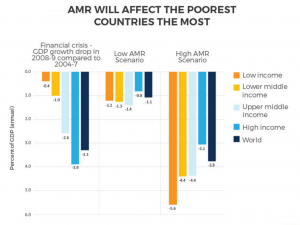

Study summary: To make the case that all countries must help stop AMR, the World Bank calculates how much AMR could cost the global economy. The Bank simulates the growth of AMR to the year 2050 in two scenarios: “low AMR impacts” and “high AMR impacts.”

The Bank’s models are built around the economic shocks of a decreased labor supply and lower livestock productivity. All economic sectors would be affected in all countries, but the poorest countries are often hardest hit, as they can lack even rudimentary medical facilities. Indeed, the growth of AMR would increase global inequality and push millions into poverty.

Beyond the economic impact, the paper considers hard-to-quantify quality of life issues. For example, gonorrhea has become harder to treat because of AMR. Alternative treatments, including injecting iodine through urethral or vaginal catheters, are more painful.

Findings:

- In the optimistic scenario, with a “low AMR impact,” global GDP loses 1.1 percent of growth a year by 2050, with an annual output shortfall over $1 trillion after 2030.

- In the worse scenario, with a “high AMR impact,” global GDP growth loses 3.8 percent a year; the annual shortfall reaches $3.4 trillion after 2030.

- Between 8 million and 24 million people would enter poverty by 2050.

- Total global exports would fall between 1.1 percent and 3.8 percent.

- By 2050, annual health care costs would rise 25 percent in low-income countries, 15 percent in middle-income countries and 6 percent in high-income countries. That could cost over $1 trillion per year.

- Global livestock production would decline between 2.6 percent and 7.5 percent, hurt by disease as well as new trade restrictions. In the poorest countries, livestock production could decline by 11 percent.

- “The lack of veterinary capacity in many low-income countries presents a substantial (and rising) risk to global economic and health security and causes a large ongoing human health burden in those countries.”

- The cost of containment measures in 139 low- and middle-income countries is $9 billion a year.

- Even half that investment would create between $10 trillion and $27 trillion in cumulative global benefits. (The Bank estimates this represents a 58 percent annual return. “AMR containment is a hard-to-resist investment opportunity.”)

- Tests of 1,606 bacteria samples in Ghana show antibiotics’ reduced effectiveness: 80 percent of pathogens were resistant to older antibiotics such as ampicillin and tetracycline and 50 percent to newer antibiotics like cephalosporin and quinolone. “Most” were immune to multiple drugs.

- “That pathogens will continue to evolve also means that any new antimicrobial ‘miracle cures’ that are developed will not last.”

- Moreover, access to new drugs is a problem: Because the first-generation of antibiotics is no longer effective in many cases, one million children die each year due to treatable diseases like pneumonia and sepsis. Newer drugs are expensive and unavailable to the world’s poorest.

- Substandard and counterfeit drugs exacerbate AMR, allowing bacteria to build immunity while not curing the patient. Up to 60 percent of antimicrobial drugs sold in Africa and Asia may be low quality, “often having none, or too little, of the active ingredient.”

Helpful resources:

The CDC has an information page on drug resistance.

The Washington, D.C.-based Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics and Policy researches antibiotic resistance around the world.

This 2015 PBS Frontline documentary discusses how the widespread use of antibiotics in livestock has contributed to the rise of AMR “superbugs.” Antibiotics are not only used to target disease and as a prophylactic, but also to promote animal growth.

RAND Corporation, a nonpartisan think tank, estimates that the status quo would result in between 11 and 14 million fewer working-age adults by 2050. The worst-case scenario, RAND says, would mean 444 million dead by 2050.

A review group reporting to the prime minister of the United Kingdom has published a number of papers on microbial resistance.

Other research:

This 2013 paper in JAMA Internal Medicine estimates the number of drug-resistant staph infections (Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)) in the United States.

This 2013 study in PLoS One demonstrates how humans are contracting drug-resistant staph infections (MRSA) from livestock.

The Lancet has reported on the rise of drug resistance and The BMJ has discussed the economic cost of AMRs.

Keywords: drug resistance, antibiotic resistance, staph infections, global public health, disease and treatment, epidemics, pandemics, penicillin

Expert Commentary