With the first presidential debate before the 2020 general election one week away, journalists across the U.S. will be trying to help voters understand the importance of this national event and how it could alter the outcome of the race.

On Tuesday, Sept. 29, President Donald Trump will face off against Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden in the first of three televised debates. Their final debate is set for Oct. 22.

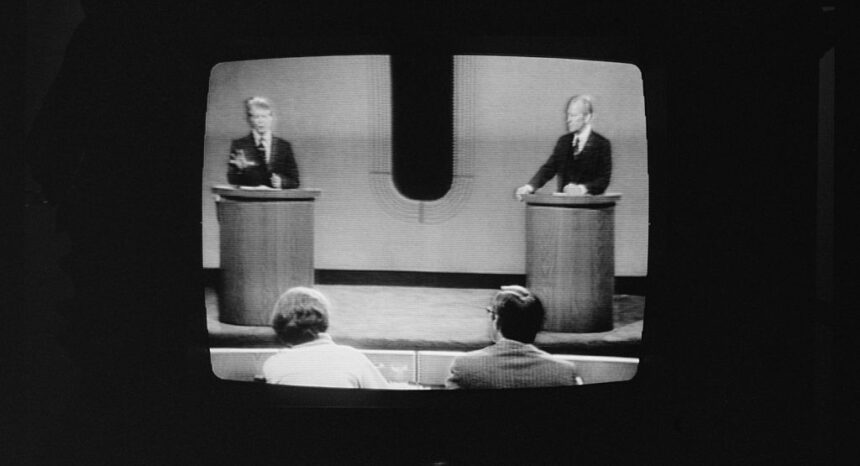

Every four years, after the major political parties’ nominating conventions conclude, U.S. newsrooms turn their focus to the presidential debates. They’re typically a chance for candidates to appear before a national audience of tens of millions of people and explain their policies, convey their likability and convince voters they are qualified for the position.

The first of the 2016 general election debates, which featured Trump and Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton, drew an estimated 84 million people, airing live on 13 television networks, according to Nielsen TV ratings. About 71.6 million viewers tuned in for the final presidential debate in 2016.

The 2020 presidential debates and the lone vice presidential debate likely will be the most-watched TV programs this fall, media consultant Brad Adgate writes in Forbes magazine.

Adgate explains: “With the pandemic curtailing campaign rallies, a polarized political climate, the ratings spike of newscasts, the lack of original programming content on competitive cable networks, an unpredictable president who constantly courts media attention (including expected complaints about the moderator and format) and recent debates setting TV audience records, the 2020 debates could average 100 million viewers, joining ten Super Bowls (including this year’s) and the M*A*S*H finale in 1983 to reach that audience threshold.”

Considering the substantial public interest and stakes, we’ve gathered and summarized three academic research articles we think journalists covering the presidential debates will want to know about. They offer key insights into topics such as:

- How candidates have used different forms of aggression during presidential debates — and how aggressive words and gestures can backfire.

- Whether presidential debates help voters learn more about public policy issues.

- The likelihood that voters’ opinions of candidates will change after watching presidential debates.

- How the debate performance of sitting presidents often falters but rebounds leading up to the general election.

——

Learning From the 2016 U.S. General Election Presidential Debates

Kenneth Winneg and Kathleen Hall Jamieson. American Behavioral Scientist, 2017.

In this study, University of Pennsylvania researchers look at whether people gained knowledge about policy issues and changed their minds about the candidates after watching televised presidential debates in 2016. What the two scholars learned: While debate watchers gained knowledge about policies, their assessment of candidates’ qualifications did not change. Neither did their opinions of whether individual candidates, if elected, would threaten the well-being of the nation.

The researchers also find that people who watched a debate and then broadcast or cable news coverage of it had higher levels of knowledge about the two major party candidates’ stances on campaign issues than did those who did not follow postdebate coverage.

To study the impact of debate watching, the authors examined data collected via an online survey of U.S. adults recruited to watch the first and third presidential debates in fall 2016. A total of 5,145 people answered a series of questions before and after viewing the first debate, which aired Sept. 26, 2016. A total of 5,241 adults responded to questions before and after the third debate, aired Oct. 19, 2016. Participants completed the postdebate surveys within 48 hours of each debate.

To measure changes in knowledge, participants were asked before and after each debate which candidates supported and opposed issues such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership and increasing the federal minimum wage. Participants also were asked whether they watched, followed or listened to any of the news discussions right after the debate or the next morning.

About two-thirds of debate watchers reported following at least some of the coverage after the debate.

Study participants also were asked before and after the debates whether Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump were more qualified to become president. Watchers of the third debate were asked an additional question: whether Clinton or Trump, if elected, would threaten the country’s well-being.

Survey results show the debates had little impact on participants’ opinions of these matters.

“Going into the debates Clinton was seen by a 2 to 1 margin as the more qualified candidate (54% vs. 26% in the first debate and 52% vs. 24% in the third debate),” write the authors, Kenneth Winneg, who is managing director of survey research at the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania, and Kathleen Hall Jamieson, director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center.

Winneg and Jamieson find that watching the third debate had little effect on study participants’ opinions about whether Clinton and Trump would be a threat to national wellbeing.

Before that last debate, 50.3% of debate watchers saw Clinton and 63.4% saw Trump as a threat to national wellbeing. After the debate, 50.2% said Clinton would be a threat, 63.2% said Trump would be.

Making Debating Great Again: U.S. Presidential Candidates’ Use of Aggressive Communication for Winning Presidential Debates

Daniel John Montez and Pamela Jo Brubaker. Argumentation and Advocacy, 2019.

This paper explores how political candidates used various forms of aggression in 2015 and 2016 during presidential debates — including insults, hand gestures and facial expressions — in order to manipulate conversations, damage opponents’ reputations and elicit responses from the audience. Among the key findings: Democratic candidates were three times less aggressive than Republican candidates during the six presidential primary debates analyzed. Of all the candidates who participated in the presidential primary debates and general election debates that researchers studied, Donald Trump committed the most acts of aggression.

Authors Daniel John Montez and Pamela Jo Brubaker, researchers at Brigham Young University, note that the Republican primary debates and general election debates likely grew more aggressive “as a response to Donald Trump’s aggressive communication and the rising political stakes as Trump continued to dominate the polls during the election cycle.”

The authors analyzed two presidential primary debates from each major political party and two general election debates. Through content analysis, they discovered a total of 2,441 instances of social, verbal and non-verbal aggression among all candidates.

The researchers note that the most common form of social aggression was an attack on another candidates’ character by discrediting their competence, trustworthiness or goodwill. Meanwhile, verbal aggression included insults and short outbursts and nonverbal aggression tended to consist of gestures, finger pointing and facial expressions.

“Within the primary debates of both parties, trailing candidates used more aggressive communication against their political front-runners to help them stay in the game,” Montez and Brubaker write. “Similar patterns emerged during the general election debate as Hillary Clinton attempted to match her opponent’s communicative behavior by using 23 times more direct social aggression than she used in the Democratic debates analyzed.”

The researchers explain that nonverbal aggression can backfire, costing candidates votes. They point out that Republican candidate Marco Rubio and Democratic candidate Bernie Sanders led their parties in the use of this type of aggression. They add that nonverbal aggression was the only type of aggression that Clinton used almost as much as Trump during the general election debates.

“In other words,” the authors write, “Trump’s nonverbal aggression may have resonated with audiences out of familiarity with his persona, but, in general, trailing presidential candidates should avoid using such aggression. Similar to past research on nonverbal violations exhibited by presidential candidates, nonverbal aggression typically does not resonate well with voters.”

Do Presidential Debates Matter? Examining a Decade of Campaign Debate Effects

Mitchell S. McKinney and Benjamin R. Warner. Argumentation and Advocacy, 2013.

After analyzing 22 academic studies on U.S. presidential debates held between 2000 and 2012, the researchers found that:

- The vast majority of voters don’t change their minds about which candidate they support based on what they see and hear during a general election presidential debate.

- A lot of people — nearly 60% — do change their minds after viewing presidential primary debates. “The large amount of candidate-to-candidate switching following primary debates suggests these early campaign forums are particularly useful for voters who are weakly committed or perhaps express their predebate choice based largely on candidate name recognition or front runner status before greater exposure to lesser known candidates,” write the authors, Mitchell S. McKinney and Benjamin R. Warner of the University of Missouri.

- Both Republican and Democratic candidates tend to be viewed more positively following general election and primary election debates. This, the researchers write, “reminds us that campaign debates are not zero-sum for candidates as both or all candidates on the debate stage might benefit from their debate performance.”

- Although sitting presidents often falter during the first general election debate, they often rebound. “After an initial lackluster first debate performance, it appears that incumbents often rebound in their subsequent debates, as our data show for both George W. Bush in 2004 and Barack Obama in 2012 (and also as Ronald Reagan rebounded nicely in his second debate in 1984),” McKinney and Warner write.

- Viewing presidential debates boosts voters’ feelings of confidence in their own political knowledge — especially for voters who felt less informed before the debate. “In this manner,” the researchers explain, “campaign debates serve as something of an equalizer among the political information haves and have-nots.”

If you’re looking for more research on presidential debates, please read our roundup of earlier research on the topic. For more on elections, check out Tom Patterson’s Election Beat 2020 series.

Expert Commentary