A shell of a shell is how a cynic might describe the 2020 U.S. presidential election’s national party conventions. Devoid of huge crowds and conducted mostly online over the next couple of weeks, they likely will be the most subdued conventions in history.

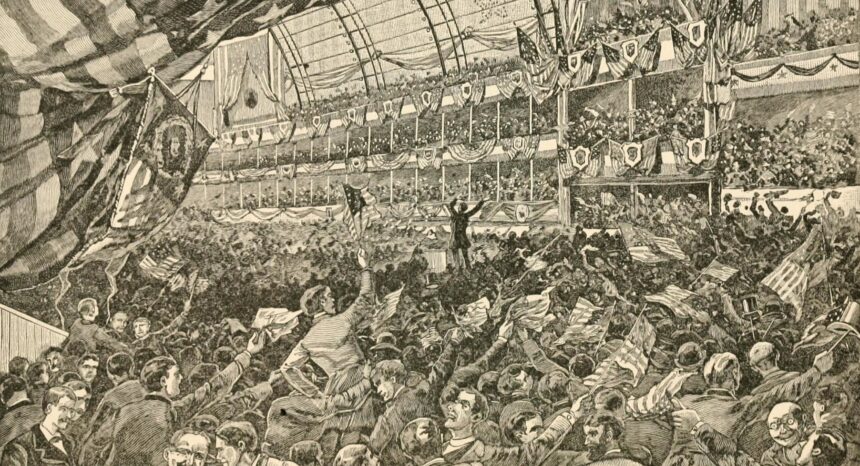

The national party conventions were once rollicking affairs, none more so than the Democratic gathering in 1924. The Democrats had thought — in the wake of the Teapot Dome scandal that had rocked the Republican administration of Warren G. Harding — that they could recapture the White House.

But the Democrats had a tempest of their own to deal with. The northern wing of the party wanted New York governor Al Smith, a Catholic who despised the Ku Klux Klan and promised to end prohibition. The Klan-tolerating, prohibition-supporting southern wing wanted the more conservative William McAdoo, son-in-law of Woodrow Wilson. For nine days, sometimes with fisticuffs, the two sides battled on the convention floor with neither candidate able to muster the required two-thirds majority. After an astounding 103 ballots, Smith and McAdoo released their delegates, and the convention turned to John W. Davis, a little-known Wall Street lawyer. Journalist H. L. Mencken likened Davis’s nomination to “France and Germany fighting for centuries over Alsace-Lorraine, and then deciding to give it to England.”

Some of the drama was stripped from convention politics when the Democrats in 1936 dropped its two-thirds rule in favor of simple-majority rule, which the GOP had always used. But the change was of small magnitude compared with the post-1968 reform that required states to choose their convention delegates through either a primary election or open caucus. Ever since, one of the contending candidates has always accumulated enough delegates in advance of the convention to secure the nomination. Formal nominating power still resides in the convention, but the real power rests with the votes cast in the primaries and caucuses.

If the rule changes have deprived journalists of a gripping story to tell during the national party conventions, these affairs continue to be important to voters. The marathon-like length of a U.S. presidential campaign works against the need of voters to pay attention if they seek to be informed about the choices they face. Political junkies aside, few citizens have the time or interest to regularly engage a campaign that stretches out for more than a year. But there are two moments in the campaign — the national party conventions and, even more so, the general election debates — when voters are more willing than usual to listen and learn. These moments are not to be squandered. Research indicates that the conventions and general election debates are when voters’ understanding of what the candidates represent has the greatest increase.

Journalists and voters are in different places at the time of the conventions. Having followed the candidates for months on end, journalists find almost nothing new in what the nominees and their supporters are saying, which diminishes the newsworthiness of what’s said. But much of what’s said is new to many voters. And it’s delivered in a way — lengthy presentations rather than 10-second sound bites and 30-second ads — that can heighten their understanding of the policies that the nominees are likely to pursue if elected.

As coronation events, conventions do not have the newsworthiness that they had in the days when they were a time of decision. After the post-1968 reform of the nominating process, the broadcast networks cut back sharply on their earlier gavel-to-gavel coverage. As this was happening, the focus of the convention coverage was also changing. Whereas the cameras had earlier been aimed mostly at what was happening on the floor of the convention, they were now aimed mostly at the anchors, journalists, and pundits in the broadcast booth. It was more than a shift in camera angle. It produced a change in perspective. Whereas what was being said on the convention floor related largely to the policies that the nominee would pursue if elected, what was being said in the broadcast booth was mostly about the nominee’s chances of winning, tactics, voter appeal, and the like. It was the journalists’ version of a campaign rather than the candidates’ version.

Journalists have plenty of opportunities during the campaign to bring their version to voters’ attention. Conventions are the only real opportunity for the nominees to address the American people at length and on their own terms. It’s not unreasonable to conclude that the nominees have earned the opportunity, and there is plenty of evidence to indicate that voters gain from listening to them and their supporters. That axiom would apply also to stories derived from what journalists observe during a convention. In the 1970s, as journalists were increasingly shaping the political narrative, Washington Post editor Russell Wiggins said that they need to get off “the stage” and back into “the audience.” The likelihood of that today is zero, but there are times in a presidential campaign when they should take a back seat. The upcoming national party conventions are among those times.

Ironically, the pandemic-defined convention proceedings will provide journalists more opportunity than usual to highlight substantive issues. With visual access to what’s happening on the convention floor and what’s being streamed, there’ll be an abundance of voices and material from which journalists can choose. Apart from the great difference in the two nominees’ character, the issues of this election are large and important, including the nominees’ plans for containing the pandemic, for rebuilding the economy, for enhancing economic security, for restoring the fiscal health of states and cities, for handling immigration, for defining America’s role in the world, and on and on. If the convention period passes without voters having acquired a clearer sense of what’s at stake in this election, much of the fault will rest with America’s journalists. Their occasional justification for underplaying policy issues — that voters aren’t interested — doesn’t apply. Polls indicate that voters are intensely interested this time around. For the next couple of weeks at least, journalists should give voice to what the presidential nominees are saying.

Thomas E. Patterson is Bradlee Professor of Government & the Press at Harvard’s Kennedy School and author of the recently published Is the Republican Party Destroying Itself? Journalist’s Resource plans to post a new installment of his Election Beat 2020 series every week leading up to the 2020 U.S. election. Patterson can be contacted at thomas_patterson@harvard.edu.

Further reading:

Joseph Cera and Aaron C. Weinschenk, “The Individual-Level Effects of Presidential Conventions on Candidate Evaluations,” American Politics Research 40 (2012): 3-28.

Thomas E. Patterson, “News Coverage of the 2016 National Conventions: Negative News, Lacking Context,” Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, September 21, 2016.

Thomas E. Patterson, The Vanishing Voter: Public Involvement in an Age of Uncertainty (New York: Knopf, 2002).

Aaron Weinschenk and Costas Panagopoulos, “Convention effects: examining the impact of national presidential nominating conventions on information, preferences, and behavioral intentions,” Journal of Elections 4(2016): 511-531.

Expert Commentary