Tax increases targeting the top 1 percent did not stop their income growth and may have helped the economy overall, according to a new study.

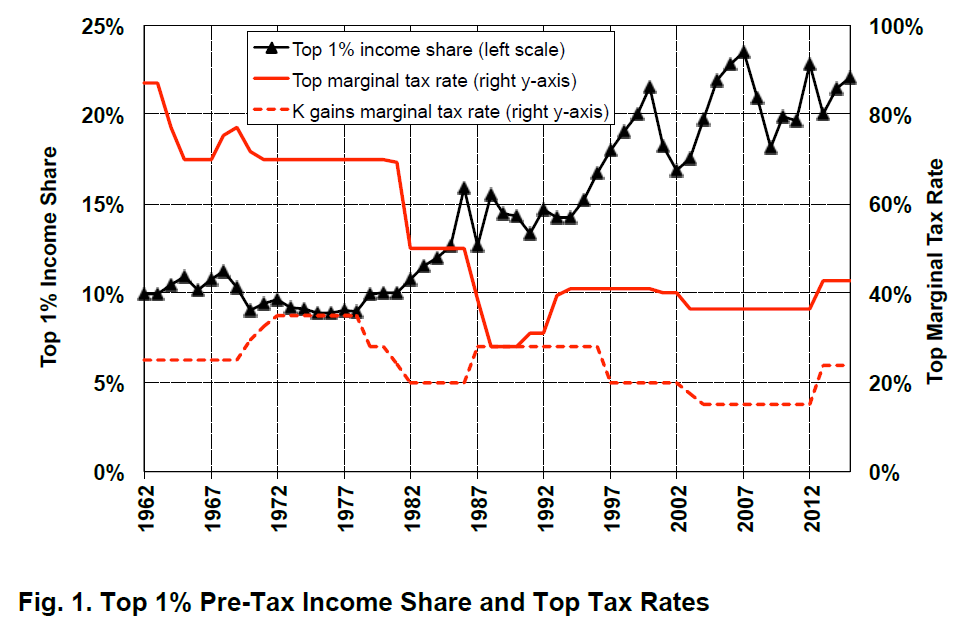

The issue: Tax rates, a deeply partisan issue in American politics, are often framed as an argument over how to fuel growth. Lower taxes, according to Republican doctrine, leave money in the hands of workers and businesses, allowing them to invest and drive the economy. Higher taxes, Democrats say, allow the government to fund infrastructure that will encourage business, while also lifting up the poorest with social programs. In the past few generations, Republican presidents have tended to cut taxes and Democratic presidents tended to raise them. Since the 1970s, the top 1 percent of earners have seen their tax liabilities fall dramatically (see graph below) and their share of earnings jump.

The United States has a progressive tax system, where higher incomes are taxed at higher marginal rates.

In 2013 Barack Obama’s administration increased the top marginal tax rate for individuals making over $400,000 per year by about 6.5 percent on their labor to 39.6 percent (before deductions). Those individuals earning over $200,000 per year also saw their capital income tax (tax on capital gains, dividends and profits from the sale of real estate) rise by about 9.5 percent. As the top 1 percent of earners enjoy about 80 percent of realized capital gains, the vast majority of these increases accrued only to the top 1 percent. The changes (included in the Affordable Care Act surtax and the expiration of tax cuts enacted under George W. Bush) were the largest increase in top tax rates since the 1950s.

So how did taxpayers respond to the reform and how did the new taxes impact income inequality?

An academic study worth reading: “Taxing the Rich More: Preliminary Evidence from the 2013 Tax Increase,” published by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), November 2016.

Study summary: Emmanuel Saez, an economist at the University of California, Berkeley, looked at how the top 1 percent of earners responded to Obama’s tax reforms in early 2013. The top 1 percent are individuals making more than $400,000 and families earning more than $450,000 per year.

For control groups, he also looked at the top 1 percent to 5 percent — those with incomes between $170,000 and $400,000 in 2013 — who were only slightly affected; and the top 5 percent to 10 percent, those with family pre-tax gross incomes of between $120,000 and $170,000, whom he found essentially unaffected by the tax change.

Using annual data from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Saez compared the years 2011 and 2015 – before and after the reform.

Taxpayers can often choose when to pay taxes on their capital gains: Electing to realize gains in 2012 was tax-advantageous relative to realizing in 2013, when the rate was higher under the new tax regime. Taxes on labor can be retimed, too: “Employer and employees could potentially agree to shift wage income (such as bonuses) into 2012. Business income can be re-timed by postponing costs. […] Dividends, particularly in closely held firms, could also be accelerated in 2012.”

But “income retiming,” as this phenomenon is known, is not an option for multiple years in a row. So by looking at 2015, we should see a more accurate picture of the tax reform’s impact.

Saez also looked at charitable giving by the top 1 percent: “High income individuals have an incentive to postpone charitable giving from 2012 to 2013 […] because charitable giving can be deducted from income to reduce the amount of tax paid.” He expected to see a decline in gifts to charities in 2012 (when it was clear the tax increase was coming) and a spike in 2013. Past research suggests that such giving does respond to tax rates, especially in the short-run. “Charitable giving is potentially a useful proxy for the real economic incomes of top income taxpayers,” Saez wrote.

Findings:

- Top income shares have continued to grow, suggesting that Obama’s tax increases did not reduce economic activity at the top. Between 2011 and 2015, the share of income going to the top 1 percent has continued to increase at a rate similar to the increase between 2009 and 2011.

- Since 1990, the best growth for the bottom 99 percent happened in two periods after tax increases on top earners: the late 1990s and following Obama’s 2013 tax increase on the highest earners. This suggests that the top marginal tax rate increase helped the overall economy.

- The top 1 percent of income earners shifted about 11 percent of their 2013 income to 2012 to pay the lower tax rate. This “income retiming” was larger for capital gains than for employment income. (The top 1 percent of income share jumped 3.2 percent in 2012, the largest spike since the 1980s. In 2013, this group’s share fell to similar levels as 2011. That fall was as large as the fall during the Great Recession. As both 2012 and 2013 were similar in terms of market growth and economic output, the spike and fall cannot be explained by other factors. “The most plausible explanation is income retiming.”)

- This spike and fall was about three times larger for the top 0.1 percent (families with annual incomes over $2 million).

- There is no evidence of such change in reported incomes for the two control groups.

- For the IRS, that loss amounted to almost 20 percent of the projected increase in revenue during the first year after the tax reform.

- Charitable giving was a surprise: Saez expected a fall in 2012 and a rise in 2013 to offset higher taxes. But he found, instead, that charitable giving spiked in 2012 and fell in 2013, “following almost exactly the path of top 1 percent income.” This suggests top earners were not strategic about how to use charity to offset their tax liabilities.

Other resources:

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, a rich-country think-tank, publishes annual tax return data for its 35 members.

Two well-known Washington D.C. think tanks focus on taxes. The conservative-leaning Tax Foundation publishes historical tax rates. The Tax Policy Center has been called liberal.

PBS explains how a marginal tax rate works and includes a (slightly outdated) calculator allowing users to compare their theoretical tax liability in different countries.

In 2015, the Pew Research Center found 59 percent of Americans feel Congress should completely overhaul the tax system. Seventy-five percent of Democrats and 52 percent of Republicans are bothered by corporations not paying “their fair share” in taxes.

The American tax code is over 9,000 pages long.

Other research:

A 2012 paper on behavioral responses to taxation lays some of the groundwork for this study.

A 2016 paper shows that the top 1 percent have doubled their share of pre-tax earnings since the late 1970s.

Keywords: taxes, income inequality, rich-poor divide, class

Expert Commentary