On any given day in the United States, approximately 70,000 juvenile criminal offenders live in residential detention facilities, and about 68% are racial minorities, according to the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ). Many thousands of others are held in detention centers awaiting trials. The overall number of juvenile offenders in such facilities has declined 42% since 1997, when the figure was 116,000, but tens of thousands of juveniles are still detained for the first time each year, often beginning a long-term pattern of contact with the criminal justice system.

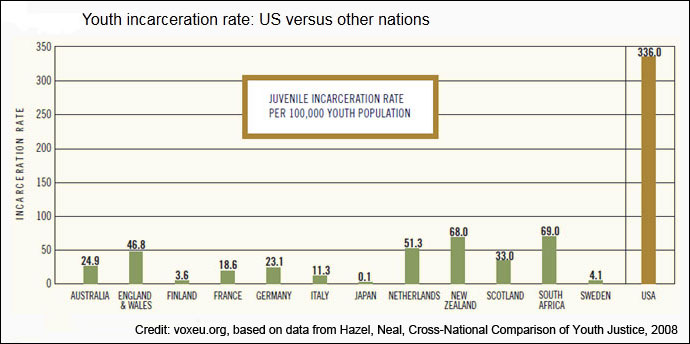

The rate of incarceration of American youth, typically topping 300 per 100,000 in a given year, is estimated to be at least five times higher than the rate of the next highest developed country, South Africa. For every 100,000 African-American juveniles in the United States, 521 were in a residential facility, compared with a figure of 112 among white youth, according to 2011 DOJ statistics. Meanwhile, U.S. juvenile court judges continue to have wide discretion and some consistently hand down longer sentences, an issue that has come under scrutiny.

In the wake of events in Ferguson, Cleveland and New York — where the killing of unarmed black men and boys by police officers touched off a national debate and spurred a sustained “Black Lives Matter” protest and campaign — moral and legal questions remain about the treatment of minority youth. Research and advocacy organizations such as the The Sentencing Project have pointed to what they characterize as a “cascade of disparities” throughout the criminal justice system, which includes “uneven policing” that makes it much more likely young black males in particular will be confronted, arrested and detained.

Such treatment can exacerbate existing inequalities, as a criminal record and the experiences associated with time in the criminal justice system can undermine educational and working lives. Juvenile detention is also costly: A 2011 report for the Annie E. Casey Foundation, “No Place for Kids: The Case for Reducing Juvenile Incarceration,” notes the “jaw dropping” sums of state and federal taxpayer dollars spent on this system — up to $88,000 a year to incarcerate a juvenile for 9 to 12 months, with states spending a combined $5 billion in 2008.

Social scientists characterize this phenomenon as the interruption of “social capital accumulation,” and its impact is evaluated in a 2015 study published in The Quarterly Journal of Economics, “Juvenile Incarceration, Human Capital and Future Crime: Evidence from Randomly Assigned Judges.” The paper — authored by Brown University’s Anna Aizer and MIT’s Joseph J. Doyle, Jr. — analyzes 10 years of data on approximately 35,000 juvenile offenders in Chicago. (See the authors’ study summary.) Because judges are randomly assigned to cases, Aizer and Doyle are able to examine how incarceration impacts a youth’s life chances, as “differences in incarceration between juveniles are attributed to the effect of the judge and not individual characteristics of the juvenile or the case, as are differences in outcomes.”

The study’s findings include:

- The data suggest that “assignment to a judge with a high incarceration rate in other cases leads to a significantly lower likelihood of high-school completion and a significantly higher likelihood of incarceration as an adult, including incarceration for violent crimes.”

- Juvenile incarceration decreases the chances of high school graduation by 13 to 39 percentage points and increases the chances of incarceration as an adult by 23 to 41 percentage points, as compared to the average public school student in the same area.

- The researchers note that, “although incarceration of these juveniles is intended to be short in duration (one to two months), it can be very disruptive. Once incarcerated, juveniles are unlikely to ever return to school.” Further, they are “more likely to be classified for special education services due to behavioral/emotional disorders rather than a cognitive disability.”

- A basic cost-benefit analysis indicates that the current system is not optimal: “If juvenile incarceration either enhanced human capital accumulation or deterred future crime and incarceration, a tradeoff could be considered. Rather, we find that for juveniles on the margin of incarceration, such detention leads to both a decrease in high school completion and an increase in adult incarceration.”

Aizer and Doyle suggest that substitutes — electronic monitoring or enforced curfews, for example — for juvenile incarceration are warranted, and that other rules and systems should be reexamined: “In addition to reducing juvenile incarceration, policies that address the low rates at which juveniles return to school upon release by providing additional support and resources for these at-risk juveniles may also be effective in reducing the negative impact of incarceration on human capital accumulation and other outcomes.” Finally, policies that make increased contact with police a near certainty also should be revisited. “Many states have adopted policies of increasing police presence in schools which has led to an increase in juvenile arrests for relatively mild infractions. If this leads to an increase in juvenile detention, which seems likely, then the continued expansion of this policy has the potential to reduce high school graduation rates for those directly affected.”

Keywords: criminal justice, race, African-American, youth

Expert Commentary