The issue: Recurrent failures in the U.S. government’s executive and legislative branches to agree on spending during Barack Obama’s presidency resulted in a downgraded credit rating and a government shutdown. Other episodes — such as a Congressional deadlock over funding an emergency bill to combat the Zika virus — also highlight how polarized the American electorate has grown.

Some theorize that this split is due to the increasingly fragmented media — with, for example, Fox News pushing a conservative agenda and MSNBC leaning liberal. Until the 1980s, most Americans could choose from only three evening network news broadcasts; each offered a seemingly neutral take on the day’s events. These days, pay-for television allows anyone to watch programming that reinforces his or her biases, or watch entertainment during the traditional news hour and skip news altogether. The fragmentation of the media has given voice to explicitly ideological outlets and once-marginal ideas.

The divide between right and left sometimes seems unbridgeable, presenting long-term challenges to the American government’s ability to function.

An academic study worth reading: “Income Inequality, Media Fragmentation, and Increased Political Polarization,” published in Contemporary Economic Policy, August 2016.

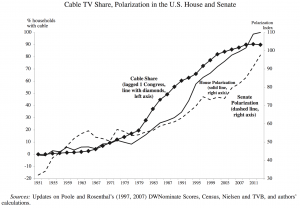

Study summary: John Duca and Jason Saving, economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, sought evidence that media fragmentation plays a bigger role in polarization than income inequality. For their analyses, they looked at variables across six decades: indexes of polarization in the U.S. House and in the Senate, family income data from the Census Bureau and the percentage of Americans with cable or satellite television. The House and Senate data show polarization to have increased rapidly since the 1980s, but do not show a cause.

Findings:

- The growing plurality of news sources as well as the increasing access to cable television made the greatest contribution to political polarization. Two phenomena, or a combination of the two, are responsible: Individuals seek out “self-reinforcing viewpoints rather than be exposed to a common ‘nightly news’ broadcast” — this is sometimes called siloing. Also, individuals are jettisoning news programming for entertainment, “thereby reducing incidental or by-product learning about politics.”

- The decreasing exposure to alternative views and the increasing buttressing of one’s own views has combined to create less sympathy for others’ views and less of an ability to understand others’ views. “This may be reinforced by a tendency for political differences to be decreasingly addressed through genuine debate and increasingly replaced with media coverage of political vilification or grandstanding.”

- Inequality — the divide between rich and poor — may have contributed to political polarization, but less than media fragmentation.

- Duca and Saving test for a number of trends but find no statistically significant associations with generational attitudes, voter partisanship, economic conditions or campaign contributions. But they do find associations with income inequality and media fragmentation.

- There is some evidence that Congress is more polarized at the beginning of a president’s second term.

Other resources for journalists:

To track how members of Congress vote, the Senate.gov and House.gov websites detail voting records, as does the crowd-funded Govtrack.us.

The Pew Research Center published an extensive investigation into political polarization and media habits in 2014, including five key takeaways. Pew in 2016 looked at ideological gaps between people with different education backgrounds.

Morris Fiorina, a prominent political scientist at Stanford University, has cautioned journalists on how they interpret the Pew findings.

Other research:

Harvard University Professor Thomas Patterson’s book, Informing the News: The Need for Knowledge-Based Journalism (Vintage 2013), describes, among other things, how in 1987 the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) rescinded the Fairness Doctrine, giving rise to extremely slanted radio and then cable news talk shows. The Fairness Doctrine, Patterson writes, “had discouraged the airing of partisan talk shows by requiring stations that did so to offer a balanced lineup of liberal and conservative programs. Once the requirement was eliminated, hundreds of stations launched talk shows of their choosing, the most successful of which had a conservative slant.”

People who consume sharply partisan news coverage are less likely to believe the truth even when they are presented with clear evidence they are wrong, according to research published in 2016 in the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication and flagged by the Poynter Institute.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia discusses its methodology for indexing political polarization.

Journalist’s Resource profiled a 2016 study in Political Communication on how media coverage of partisan polarization increases the belief among voters that the electorate is polarized. It also discusses how voters moderate their views in response.

Keywords: Polarization, party politics, cable news, right and left, conservative and liberal

Expert Commentary